Remembering my life, I am trying to follow, to find for myself, and for others too, especially the young, the answer to the question of how life gets woven into art and how art reflects life.

— Mikhail Zharov in Zharov Tells (1970), quoted in Bill Morrison’s The Village Detective: A Song Cycle (2021)

BILL MORRISON LOVES the sea.

He swims in the ocean all year in an elastic knot of family and friends. They embrace challenging conditions across changing seasons at either of Long Island’s headland ends. Through winter, they don neoprene and take on the Atlantic from Brighton Beach; each summer, they jump into the Sound at the North Fork and swim all day to Connecticut. Open water is where Morrison bonds with those close to him. Fittingly, there are rituals; the East Village-based filmmaker organizes a New Year’s Day Brooklyn plunge, followed by lunch on the boardwalk at a Russian restaurant that faces the surf.

Maybe The Village Detective: A Song Cycle (2021) was Morrison’s destiny. Provoked by four sea-scarred reels of a Russian movie, it definitely was his opportunity. For it is Morrison’s most explicitly personal work, a feature-length essay pondering “the question of how life gets woven into art and art reflects life,” which Morrison has actor Mikhail Zharov pose twice, at the film’s beginning and, again, at its end. In between its introduction and conclusion, The Village Detective clarifies how time itself has been the evolving preoccupation of Morrison’s works and, consequently, their most significant contribution, not simply to the history of film but to the practice of history.

The enthralling beauty of motion-picture decay once more draws Morrison’s eyes. But there are noteworthy distinctions between his latest film’s principal found footage, from the Moscow-made The Village Detective (1969), fished incidentally from the North Atlantic off Iceland in 2016, and the archived films at the core of his two most-comparable features. Unlike the hauntingly scorched silent-era movies he choreographed to original music — by Michael Gordon in Decasia (2002), Morrison’s breakthrough, and by Alex Somers in his more-expository-but-equally-poetic Dawson City: Frozen Time (2016), the filmmaker’s penultimate work — The Village Detective’s eponymous source was produced well into the age of sound, on less-combustible safety stock and in widescreen. Even more significantly, the 1969 release remains widely known to the Russian public as well as to Soviet cinema specialists. Yet, these seeming departures from the documentary artist’s prior oeuvre only amplify the fundamental consistency of Morrison’s vision and methods. Accordingly, his newest audiovisual collaboration, this time with renowned avant-garde composer David Lang, distills a theme diluted by Decasia’s and Dawson City’s sentiment-inducing resuscitation of time-marred movies otherwise lost to public sight: the filmmaker’s cultivation — more than mere revelation — of histories seeded by disfigured finds.

Once upon a time, there was a young lad. He walked and roamed, deep in the midnight, he was a regular at the cemeteries.

— Zharov as Koudrayash in Thunderstorm (1934), quoted in The Village Detective (2021)

Across his career, Morrison has regularly roamed the cemeteries where old films are buried, exhuming decomposing movies to compose new histories. The Film of Her (1996) spawned the DNA from which the content and form of his recent film art about film history has evolved. This evocatively expository short — edited to music by Bill Frisell and previewing the narrative titling that returns in more-developed form in both Dawson City and The Village Detective — relates the heroic intervention of Library of Congress employee Howard L. Walls, who singularly saved a singular trove of early-cinema paper prints from mindless disposal in the 1940s.[1]

The Film of Her explicates a vital point, one latent in Dawson City and The Village Detective: official archives are inevitably, interminably incomplete. Scholarly subjectivity, the capriciousness of credentialed authority, and, most of all, fate, determines what archives do and do not conserve. Alas, we have little idea of all that they have not conserved. Unexpectedly unburied footage, that was nearly not archived, after all, generated The Village Detective, much as it did Dawson City, which Morrison built from films that had slept silently for decades, blanketed by frozen Yukon ground, before their un-prophesied resurrection.

“I was hoping they were something very old,” confesses the Reykjavik archivist who received The Village Detective’s quartet of risen reels. Not only was the cinematic jetsam not very old but it was, in fact, very new — new not because the movie was released only in 1969 and airs regularly on Russian TV since then, but because the trawled footage had metamorphosed across its decades-long ocean bath. Erlendur Sveinsson’s disappointment that the found film was not a lost treasure underscores the difference between preserving the past and creating it, archiving and historicizing. It is the water-logged print’s contemporary condition, change not preservation, that triggers Morrison’s imagination, because adaptation not reclamation enables the artist’s historical poetics: The Village Detective’s contemplation of time.

Morrison’s Village Detective firstly focuses on its titular subject’s star. The screen career of Mikhail Zharov (1899-1981), an actor known by “99% of the Russian public,” began just prior to the Russian Revolution during the silent era. But it took off in the convergent ages of Stalin and sound, when he thrice (twice in 1941 alone) won the state prize named for the Soviet dictator, whose regime nevertheless imprisoned his in-laws.

Zharov’s long career across a broad swath of Soviet film history well serves Morrison, who, as he did in Dawson City, connects varied stories by deftly intercutting archival footage to narrate his Village Detective with its own primary sources. That the charismatic actor starred in dozens of films in which he captivatingly speaks (and sings) doesn’t hurt, as Morrison masterfully mines found sound-on-film featuring Zharov, consequently exploring a new (aural) dimension in his own work. In some instances, the artist visualizes his sonic research by printing optical sound strips; analogue-era wave forms dance beside an unaware Zharov, arrestingly visualizing two temporalities at once: the past of the squarish archival footage within the wider-screen, more-rectangular present of Morrison’s art.

The drowned movie’s story about a missing accordion inspires Lang’s beguiling score. Editing to the composer’s squeezebox concerto, Morrison brews anew his long-percolating essay about film’s physical history. Accordingly, his Village Detective builds toward an intense audiovisual movement that, against Lang’s plaintive accordion moans, projects the “damaged,” sound-stripped Reykjavik print in its boxy (4:3) aspect ratio (possibly because it was a version sized for TV), framed by its actual sprockets within the margins of Morrison’s wide-screen film.

Here, Morrison exhibits the art he’s honed in his silent-era chamber pieces and symphonies. When, through wavy emulsions, we read that Zharov hears the missing accordion playing in the distance, Morrison times the absent dialogue’s subtitling to address his audience directly and wittily between time-zones, between then and now, between Zharov’s Village Detective and his own Village Detective. Accordingly, the star of both movies orders us to “Hush!” and then, a minute later, pleads, “Let’s be silent,” as Lang’s languorous composition commands our concentration.

Through art, there is history in this movement’s observation of film’s material change. As we listen to Lang’s notes over the sea-salvaged footage, time itself comes into view, what it does to things and how the form of a historical source affects our perception of the past: How do the limits of what’s left to see, or what’s missing, from a print or from an archive, change what we know and feel? The expository coda to this musical meditation about the North Atlantic reels develops further these historiographical themes; Morrison startlingly samples the same denouement of Zharov’s Village Detective from its more-pristine, archived-in-Russia widescreen form as well as its quotation (formatted in yet-another aspect ratio) in Zharov’s own movie memoir, Zharov Tells (1970). These juxtapositions of different iterations of the same film — demonstrating how archival evidence cannot present an absolute vision of the past or even necessarily of a documentary source — suggests still-deeper questions: What if the four rusty reels were all we had of this film? And, even more vexingly, what would we lose if we did not have them? For they, and not their better-preserved cousins, inspired Morrison’s movie, compelling our contemplation of the past’s opacity.

I’m often asked: “How do you start out on a role?” I ask them: “Have you ever tried to untangle a tangled skein of yarn. From which end do you start?” No one knows. Each time it’s different.

— Zharov in Zharov Tells (1970), quoted in The Village Detective (2021)

Zharov’s confessed conundrum — how developing a new role is akin to untangling a skein of yarn — is Morrison’s resounding challenge in starting a new film. The artist begins with archival footage, filmography not historiography, and builds out historically from moving-image sources. Morrison must therefore wrestle with the mind-mangling freedom to choose where to start and how to proceed — not because history is haphazard, but because in his practice it’s not preconceived. The documentary creates the past, not the other way around. Consequently, Morrison’s films document what historians actually do but what only the most self-aware acknowledge and the most creative can express — how their work imagines the past.

Morrison’s Village Detective begins with Morrison, played by Zharov. The film’s first four minutes, before its title, comprise an establishing prologue, presented in an epigraphic exchange between Zharov characters addressing Morrison’s work. In the Pirandello-esque sequence, the actor unnervingly stares at us in close-up donning different guises: a balalaika-strumming bard in Thunderstorm (1934), a youthful-if-weary, cigarette-puffing investigator in Engineer Kochin’s Error (1939), and playing himself in Zharov Tells (1970), his late-career autobiography in which he oracularly pontificates.

In Zharov, Morrison finds a transhistorical alter ego, an actor he casts to ventriloquize his own reflections about his practice. And because we can hear Morrison here, we can see him too: looking at his monitor as he edits and looking at us from the screen, through Zharov’s eyes. It’s eerily intimate. When the film’s first expository title invokes the first-person to convey how the filmmaker learned of the recovered reels — in an email from his friend Jóhann Jóhannsson, the late-Icelandic composer with whom he collaborated on The Miners’ Hymns (2010) and to whom he dedicates The Village Detective — the “I” seems matter-of-factual, because Morrison has already been addressing us, spectrally, via Zharov.

Morrison’s movie, then, is about two detectives: Zharov’s character, on the screen, searching for an accordion in a Russian village, and Morrison’s filmmaker, behind the screen, searching for new histories from old evidence via art in the East Village. It’s this frankly self-reflexive consideration of his own practice, expressed through his practice, that most distinguishes The Village Detective from Morrison’s prior works. Accordingly, the filmmaker’s quotation of Zharov’s reflection — “When I work in the theater, I long for cinema. When I work in theater, I miss cinema” — might equally apply to the artist’s own career, which has straddled stage and screen, music and movies, since he began creating projections for multimedia productions downtown at the Ridge Theater in the 1990s.

His beat goes on. Last December, uptown at the Maysles Documentary Center, I caught an audiovisual duet performed between Morrison and his friend and frequent collaborator Bill Frisell, the virtuoso jazz guitarist and composer. The video artist spun archival footage interspersed with personal recordings (including POV camerawork by his cat, Curly) from a computer console beside the musical artist playing to the screening scenes. The crossmedia performance was, in effect, an extended riff about Zharov’s “question of how life gets woven into art and how art reflects life,” for music has been central to Morrison’s art and life.

Art, Fyodor Ivanovich, belongs to the people. Of course, Cinema has the most mass reach compared to the other arts. But, Fyodor Ivanovich, Music is meant to educate men, not only aesthetically, but also, if it’s possible to say so, politically as well. Song helps us build and work.

— Gennady Pozdnyakov (Roman Tkachuk) addressing Fyodor Ivanovich Aniskin (Zharov) in The Village Detective (1969), quoted in The Village Detective (2021)

In reporting his missing accordion, Pozdnyakov, the forlorn musician who directs the village’s social club, channels Morrison. The filmmaker takes and makes music seriously. He frequently screens his works with live performances of their bespoke compositions, and his films’ optic tones look and feel scored more than scripted. Moreover, music is elemental to Morrison’s historical poetics, to his artdocs’ transhistorical audiovisualization of now and then at once. Their sonic design renders the present, present; sound informs viewers that history is not fixed back then but made now by the artist interpreting research before their eyes. Music resonates process, compelling the audience’s active aural as well as visual engagement with the work’s contemporary creation of the past; hearing enables viewing the art of history making.

Morrison is an experimental historian, because he is an experimental filmmaker. An organic transdisciplinarity that exceeds the analytic and expressive limits of conventional historical documentary, as well as conventional historical scholarship, forms his films. Morrison’s documentary art shows time as multidimensional. In his two most recent works, which are his most overtly historical, video research is a source for analysis not a mere illustration of narration. Accordingly, in Dawson City and The Village Detective, Morrison, like any responsible historian but too few historical documentarians, demonstrates his respect for his sources (and for his viewers) by informatively-yet-unobtrusively citing on-screen the footage we see as we see it.

Both Dawson City and The Village Detective depart from most of Morrison’s prior works in their deployment of on-camera interviews as well as expository titling. Talking heads are scarce, but, when they do appear, they are informants about the patrimony of visual evidence, not cameo narrators. Each film’s titling, however, is extensive and expansive. In addition to source citations, more prominent narrative notes visualize the filmmaker’s historical voice across both artdocs. The tone of these expository messages, though, is relentlessly poetic, never didactic; pictured words are graphic constituents of Morrison’s art, not explanations of it. Their visual rhythm is meditative; these apparitional-like epigrams surface metrically, accompanying, but never overwriting, sound and footage. They follow rather than lead the filmmaker’s principal historical tool, his editing. Correspondingly, these long-form film histories unfold in soft-edged movements, not divisive chapters. There is no voice reading a script over moving images, but there is a voice, that of the artist audiovisualizing history through them.

Morrison’s history films are, then, counterworks to Ken Burns’s productions. The works of the United States’ most celebrated maker of “historical” documentaries project defining contrasts with those of Morrison. In Burns’s televised serials, time is a given, a script outline, not something to be analyzed but something to be abided, intractably moving in one direction, steadily forward; chronology is primordial. The time of the doc moves in lock step with the march of the story told. These coffee-table-sized TV programs are audiovisualized tomes more than filmic histories. The personality-driven, PBS/NEH American Experience-style, big-budget productions synthesize, melodramatize, and super smoothly aestheticize already-published interpretations. Accordingly, they divide in print-like chapters that rely on read narration. Archival moving and still images go uncited on screen — relegated to a list of repositories in the end credits — because they’re less sources of original analysis, or even evidence, than illustrations of read writing.

The filmmaker abdicates the role of historian to writers who do not control the films’ form. Academics serve as advisers and make compelling cameos playing themselves. But collaborating scholars no more apply the art of history to the practice of film than the director applies the art of film to the practice of history. Burns’s docs are not art because they are not experimental, and they are not new histories because they are not art. Viewers need not actively engage, because neither form nor content challenges their expectations of what history is or what a Burns production will be.

Morrison’s historical art does have experimental analogues. Among documentary artists today, Péter Fórgacs stands out for the Budapest-based filmmaker’s archive-derived essays that evocatively work between image and sound to raise the past. But it is a New York precursor, Joseph Cornell (1903-1972), whose work splits my mind’s screen when historicizing Morrison. The seemingly stark differences between the artists — Cornell compulsively-but-randomly collected materials in second-hand shops, obsessively worked alone, and had difficulty deepening, let alone sustaining, professional as well as personal relationships; Morrison methodically-but-expansively researches footage in archives and robustly nurtures friendships and communities central to his art as well as his life — only render more vividly for me their intergenerational, interborough association.

Cornell’s Rose Hobart (1936) — the first-ever found-footage collage — remained the most original such artwork before Morrison’s Decasia. And, like Morrison’s creation would, Cornell’s assemblage mixed recorded music with reconstructively edited footage, which the artist stripped of its original synced sound and projected slowed-down through blue glass. Composed of clips from East of Borneo (1931), a Hollywood captivity tale that Cornell cut-and-spliced at his mother’s Flushing kitchen table, the moving-image collage’s elliptical study of its feminine subject, depends on the discordant effect between its found footage and its (underconsidered) superimposed found sound, kitschy-even-in-their-day North Americanized Brazilian songs, which provocatively maps tropical (Southeast Asian and South American) eroticas in the West’s barely repressed imaginary.[2]

Morrison’s The Mesmerist (2003), produced in Decasia’s afterglow, elucidates the Cornell connection by channeling Rose Hobart and previewing The Village Detective. Comparable in scale to Cornell’s ur-found-footage collage, which distilled East of Borneo’s 77 minutes into a 19-minute compilation essay focused on its star, Rose Hobart, Morrison’s 16-minute work recuts time-raked footage from the 73-minute The Bells (1926) to music composed by Frisell (and performed by his trio), to contrive a new story focused on a key character, played by Boris Karloff. The Mesmerist, therefore, anticipates The Village Detective’s meditation around a movie star’s role as it also previews the precarious patrimony of Morrison’s most recent found-footage work’s principal primary source. But as the filmmaker has explained, archivists were “going to chuck that decayed print of The Bells,” judging it “redundant,” because the Library of Congress already “had a pristine nitrate print” of the movie. The Mesmerist only exists because the Library fortunately gifted Morrison the otherwise-doomed reels, which the artist valued for their “beautiful dried decay.” Through mesmeric bursts of emulsifying jellyfish, Morrison exhibits the warped print’s supremely un-redundant materiality, its evanescently bubbling historicity.[3]

Correspondingly, Rose Hobart only exists because Cornell, who, like Morrison, prowled old cemeteries, ran into a copy of East of Borneo “in a typical Cornell manner, by rummaging in a junk heap. He discovered a warehouse in New Jersey where scraps of old film were discarded and being sold sight unseen, by weight, usually to be salvaged for their content of silver nitrate,” recalled Julien Levy, in whose gallery Cornell first showed his film about a film, in 1936.[4] Important history making, like important art making, is not inevitable but inspirational, as often as not the result of unscripted, unanticipated, and even accidental finds that ignite creative interventions. Viewed with Rose Hobart, The Mesmerist bridges a critical moment in the history of commercial movie culture — for The Bells was released just before the transition to sound started and East of Borneo just as it ended — as well as in the history of avant-garde cinema, between Cornell and Morrison, across the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, leading to The Village Detective.

Cornell’s interborough life, as well as his interdisciplinary art, resonates in Morrison’s practice. Notably, each artist produced a short color film generated by that life — documenting a ride on a single subway line (minus subway sounds). Morrison’s Every Stop on the F Train (2008), in under eight minutes, films each station from inside a subway car rattling west beneath Cornell’s Queens before swinging downtown under Manhattan, clipping Morrison’s East Village on its way, finally, above ground, out to the filmmaker’s beloved Brooklyn shore (every stop announced harmonically by the Young People’s Chorus of New York City sung to Michael Gordon’s a cappella score). Cornell routinely rode the 7 train, erupting west from Flushing bedrock onto elevated rails across Queens, before diving under the East River and burrowing beneath 42nd Street, to deposit the artist directly below the New York Public Library, where he researched regularly, and near the cafeterias, where he ate pie addictively. The subway fascinated Cornell, and when the IRT’s Third Avenue El, Manhattan’s last-standing elevated line, was about to come down in 1955, he hired the then-fledgling experimental filmmaker Stan Brakhage to shoot the doomed line silently in Kodachrome. Disappointed by Brakhage’s expressionistic cinematography, Cornell, who had desired a more straight-forward documentary of the condemned El, let the filmmaker complete The Wonder Ring (1955) as his own.

A few years later, though, Cornell reedited Brakhage’s footage as his own Gnir Rednow, which reversed Wonder Ring’s shots, flipping left for right, as well as its title’s spelling, for its five-and-a-half minute trip. When viewed with Brakhage’s earlier edit, Cornell’s recut conjures an antecedent of Outerborough (2005), Morrison’s archival diptych, which in split-screen runs back and forth 1899 American Mutuoscope & Biograph footage shot from a camera mounted (proto-GoPro style) to the front of a trolley crossing the Brooklyn Bridge from Manhattan (for which Todd Reynolds later composed original music).

The Third Avenue El was personal for Cornell. It’s how, after he subwayed into midtown on the 7, he headed downtown to the East Village, where he occasionally visited other artists and habitually harvested sources, in the used bookstores along Fourth Avenue, for the assemblages he constructed at the other end of the IRT, back east in Queens. Cornell’s work reached the end of the line in this neighborhood, where Morrison’s career took off. The Flushing-based artist donated Rose Hobart and the rest of his films to Anthology Film Archives in 1969, at the East Village avant-garde cinema center’s conception (as Zharov’s Village Detective opened in Eastern Europe), and staged his final show, “A Joseph Cornell Exhibition for Children,” three years later (in, what turned out to be, the last year of his life) at Cooper Union, where, in the late ’80s, Morrison completed his undergraduate art training, in the East Village, which remains his home.

Morrison’s work has been nourished by his life downtown. Below 14th Street, he’s forged foundational friendships that have produced creative collaborations with musical artists (including Lang and Frisell, whom Morrison met when the nascent filmmaker worked cleaning up at the Village Vanguard), experimental performers (notably those at the Ridge), and among his long-time East Village neighbors (with whom he cultivates the award-winning 9th Street Community Garden and Park).

The most striking resonance between Morrison and Cornell, however, is not geographical but vocational. Their works advance disciplines in which neither trained, and, therefore, was not disciplined away from experimentation. Cornell scissored-and-taped Rose Hobart (as well as built his boxes), because he was not confined by formal film (let alone art) instruction. Bill Morrison is not only an experimental filmmaker but an experimental historian, because artistic practice, not a PhD, generates his historical poetics — which The Village Detective explicates.

Where and when, how and by whom a film is viewed governs its reception. Viewing Zharov’s Village Detective in its theatrical widescreen format in Moscow in 1969 is not only distinctly different from studying a mutated full-screen print on an archive’s Steenbeck in Reykjavik a half-century later, but also from watching it on Russian TV across the intervening Soviet-and-post-Soviet decades. Correspondingly, changes around the screen over the last year have affected my own reception of Morrison’s Village Detective (which continues to debut around the world).

When I first viewed The Village Detective at its New York premiere early last fall, Moscow’s military meddling in eastern Ukraine was an offscreen clash for most of the world. As I complete this essay, early this summer, Putin’s full-blast, multifront assault on Ukraine is a global concern. Zharov’s avuncular provincial cop’s search for a missing accordion now summonses nostalgia for a more predictable Cold War. The abstractions water wrought over time on the trawled print that Morrison melodically samples intensifies my geopolitical melancholia. Movies are the ultimate nostalgia makers. Andre Bazin indelibly termed film’s fulfillment of the human desire to preserve the past, to stop time, as change mummified. It’s this wish that Morrison’s works artfully evoke and that Dawson City: Frozen Time’s title slyly cites.

Zharov’s Village Detective appeared during the gray, post-Khrushchev reign of Leonid Brezhnev, the Soviet leader whose rule (1964-1982) expired with his death, the year after Zharov died. The Cold War between 1969 and 1981, between The Village Detective’s release and its star’s demise, was one in which the conflict’s brutal nonnuclear violence remained mainly confined to the then-called Third World, where Moscow and Washington fought via proxies to the deathly detriment of multitudes. Meanwhile, the superpowers slowed their direct conflict to a disco adagio called Detente, which lasted for most of the ’70s.

Before Morrison’s Village Detective, Zharov’s Village Detective was internationally unknown. It was neither a noted work of world cinema nor one that addressed the Cold War. But the movie premiered in a period bracketed on either end by internationally iconic cinematic visions of nuclear annihilation, each produced by an expatriate superpower auteur: the Bronx-born Stanley Kubrick made (in the UK) his terrifyingly funny satire of the madness of MAD (Mutually Assured Destruction), Dr. Strangelove (1964), in the Cuban Missile Crisis’s long shadow; and the Zavrazh’e-born Andrei Tarkovsky made (in Sweden) his starkly earnest nuclear nightmare, The Sacrifice (1986), his final film, amidst renewed East-West tumult that surged in Brezhnev’s wake, during Reagan’s reign.

Those exceptional films tell us no more, and likely less, about everyday screen culture than does Zharov’s formulaically entertaining The Village Detective. The still-popular-in-Russia movie, consequently, offers a disarming suggestion about Soviet society that emotes an East-West past seemingly less perilous than today’s reality.

About a fourth of the way into The Village Detective, Morrison quotes what “Lenin reportedly said: ‘Of all the arts, the most important for us is the cinema.’” Attributed to the revolutionary when motion-picture culture was barely two decades old, the declaration resonates in video’s capacity to produce form-shifting histories, which the East Village detective’s research-derived art has achieved across the past quarter century.

Bill Morrison’s historical poetics honor his sources’ protean corporality, how they change over time. Accordingly, his artdocs do not restore or re-create something old but audiovisualize something new using old things. They neither merely reassemble archival footage into engaging cinema nor reduce the past to entertaining stories. What his films do is transhistorically weld research into contemporary art that converses between present and past.

Significantly, The Village Detective’s conclusion laps back to its introduction’s quotation of Zharov’s late-career musing about “how life gets woven into art and how art reflects life.” Like all consequential histories, The Village Detective contemplates its own subjectivity. And like Decasia and Dawson City, it projects the mercurially generative relationship between history and its sources. This is because, like all consequential art, Morrison’s films change how we see; they unfreeze time.

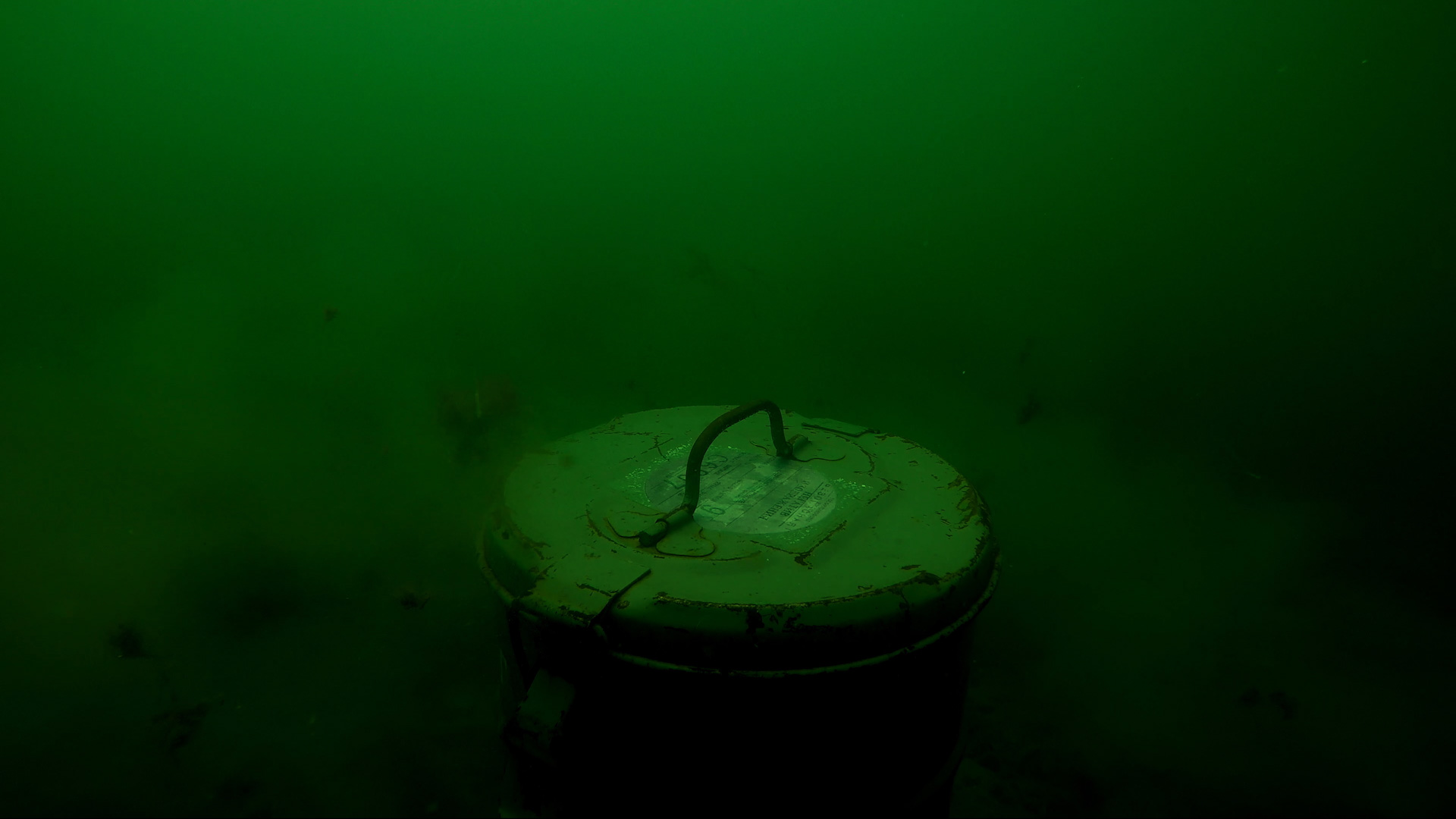

The Village Detective’s closing scene laps back, too, to its opening: a celadon-toned underwater evocation of a film canister plunging through the sea, to sleep on the ocean’s bed. That’s fitting, because the cross-currents of sensations when the lights go up after a Morrison movie are akin to those when emerging from an ocean swim: immersive renewal and arduous grasping, struggling to retain the flood of ideas that breached your consciousness while afloat but that inexorably ebb back beneath the sea by the time your toes touch the beach.

¤

[1] The Film of Her also employs document-derived, dramatized voiceover of Walls. The Great Flood (2012), Morrison’s feature about the 1927 Mississippi cataclysm (music by Frisell) further develops lyrical narrative titling, which flourishes in Dawson City and The Village Detective.

[2] Cornell recognized the emotive connection between Rose Hobart’s tropical images and sounds; in fact, he considered Tristes Tropiques as a new title for the version he reworked for posterity in the 1960s. Regarding Rose Hobart’s music, prominent scholarship remains off key. For starters, it does not distinguish between the film’s two distinct iterations: its single 1936 screening at Julien Levy’s New York gallery and its 1968 reworking for preservation at Anthology Film Archives, which remains the version heard and seen since then; prominent scholarship ahistorically assumes that the music heard on the extant version is what Cornell spun in 1936. Not atypically, for example, the essay published by the Library of Congress misstates, “Cornell played music to accompany the film using two jovial Latin music tracks by Nestor Amaral from a 78 record titled ‘Holiday in Brazil’.” Holiday in Brazil was, in fact, an LP (not a 78) recorded and released in the United States in 1957 (Mayfair), two decades after Rose Hobart premiered, and well after the Brazilian bandleader followed Carmen Miranda to New York in the 1940s and then to Hollywood in the 1950s. Regarding Rose Hobart’s 1936 exhibition, the historical reporting of P. Adams Sitney, a cofounder of Anthology who knew Cornell, is reasonable (if limited): Cornell “repeated, almost hypnotically, a passage of Brazilian music on a record player.” But Sitney’s note about the songs themselves is less reliable, citing “‘Porto Allegre’ [sic] and ‘Belem Bayonne’ from Holiday in Brazil” with no date for the LP’s release and only correctly naming one of the three (not two) tracks sampled; see, Sitney, “The Cinematic Gaze of Joseph Cornell,” in Joseph Cornell, Kynaston McShine, ed. Museum of Modern Art, 1980, 76, 88. The actual cuts heard are: “Carrupaco” (Side A, Track 3); “Porto Alegre” (A4), and “Playtime in Brazil,” (B1); the latter two repeat, hence: A3, A4, B1, A4, B1.

[3] Morrison interviewed by Scott MacDonald in The Sublimity of Document: Cinema as Diorama. Oxford University Press, 2019, 172. Morrison also used scorched material from The Bells, to less-narrative ends, in Light Is Calling (2004), scored by Michael Gordon.

[4] Julien Levy, Memoir of a Gallery. Boston: MFA Publications, 1977, 2003, 229.

¤

Seth Fein is a historian and filmmaker. Born and raised in Brooklyn, he lives and works in Queens, where he founded and operates Seven Local Film.

LARB Contributor

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Talking Cure: On Ruth Beckermann’s “Mutzenbacher”

J. Hoberman reviews Ruth Beckermann’s film, “Mutzenbacher,” loosely adapted from the 1906 novel.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2022%2F08%2FVillage-Detective.jpg)