There is no right way to tell a story of what’s happening during the COVID-19 pandemic, but there are plenty of wrong ones.

News articles, first-hand accounts, archival materials, original reporting, formal and informal records, and more will tell one version — the “official” history — about what took place. Most of it will likely center on high-level political chaos. But there are threads to the truth that no single narrative can ever cover, and which is rarely told by the people who felt the consequences of world-changing events most acutely: people at the center of the storm without any power.

So when we look back at this crisis, how will we remember it? Cinthya Santos Briones is doing her part to bring those voices to the center of how we talk about this crisis. She uses documentary photography, ethnography, and drawings to chronicle the struggles of immigrant frontline workers during the pandemic.

One woman pictured wears a surgical mask and holds a small sign that reads “The working class can’t work from home.” Another image is from inside a factory, captured in between rows of workers standing at makeshift tables and surrounded by paper littering the floor. The woman who shared this photo with Briones is packaging hand sanitizer in Brooklyn. She tells Briones that she makes $100 a day working nine-hour shifts (well below the new state minimum wage). “We always see the same thing,” says Briones. “The most impacted people are communities of color and the poor.”

Many writers and artists already know that our textbooks don't tell the full story of past events, or the people who experienced them. Ground-level social histories are often never recorded in the first place. “What is placed in or left out of the archive is a political act,” argues Carmen Maria Machado in her recent memoir, In the Dream House. Those choices add up to an incomplete record and a misunderstanding of what took place.

Briones profiles first- and second-generation Mexican, Guatemalan, and K’iche’ families working and surviving in New York City and New Jersey. “I am not just a documentarian or an artist,” Briones says of her role in the crisis. “But I have a responsibility to my community.”

Scholar Saidiya Hartman feels that same responsibility: “As a writer committed to telling stories, I have endeavored to represent the lives of the nameless and the forgotten,” she explains in an essay archiving the mid-Atlantic slave trade, “and to respect the limits of what cannot be known.”

Like Hartman, historian Monica Muñoz Martinez refuses to forget these stories and those who tell them. Her work uncovering details of violence against border communities gives us a blueprint for how we might look at this moment in a new way. “Critical remembering refuses the impulse of official state history to create one monolithic interpretation of the past,” Martinez writes in her book The Injustice Never Leaves You. Critical memories, she argues, have helped us look back at periods in our history and challenge what we have thought to be fact.

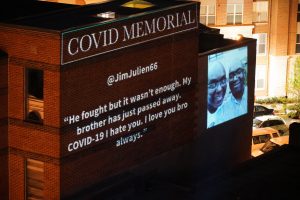

Visual artist Robin Bell is starting now, and has created a digital archive memorializing those who have died. COVID Memorial is an online collection of stories shared via email and public social-media content. According to its mission, the memorial “allows stories to speak for themselves.”

The list of memorials is long, and updates frequently. Posts on the website remember friends and family members, but also call on others to help stop the spread of the virus. “My lovely auntie died of coronavirus in a care home, alone, after a 10-year battle with Alzheimers,” reads one. “She was a nurse and spent her career helping people and deserved more than this. I’m begging you to stay home.”

Even if we stay in our homes, learn in online classrooms, and work remotely when we can, there are still times when we want to feel connected to one another in a larger way. Public monuments have traditionally served that role, uniting us around significant moments in history. And sometimes they raise the status of a memory — factual or otherwise — by paying tribute to it. With this in mind, Bell projected the COVID memorials on the side of a public building in Washington, D.C., effectively making the deaths of everyday people as meaningful as someone more important.

Just as there is more than one version of the past, there are many ways not to forget it. In her collection of untold histories, Hope in the Dark, author Rebecca Solnit offers us one: “The living are the monument” she tells us. “Remember that this is who we were and can be.”

When developers want to build private incarceration facilities, for instance, we can remember how prison labor was used to produce state-branded hand sanitizer, and how those incarcerated at Riker’s Island were paid six dollars an hour to dig mass graves. When healthcare and domestic workers negotiate their pay or benefits, we must document how they put themselves at serious risk with little to no personal protective equipment to save lives, and help them secure livable wages. When lawmakers try to suppress the vote, we will remember how Milwaukeeans stood in line for hours to cast their ballots, and make absentee and vote-by-mail resources available to everyone.

We can use this moment as an opportunity to institute radical change in our ways of living; we just need the imagination to make it happen. An example comes from one group in Chicago that has put together updates, newsletters, radio broadcasts, first-hand experiences, lists and guides, and artwork to help their communities face the crisis together while living and working apart. The Quarantine Times is both a resource for practical information and a living memorial to how Chicagoans are overcoming the pandemic.

“We all know, being in bodies right now and reading the news and from looking at the sky, that the way things are one day is completely different from the next,” says Mairead Case, a writer and teacher and the QT’s Thursday editor. “The Quarantine Times is really set up to hold all of it.”

The project provides direct support to one artist per day, via the commission of new works, for the duration of the pandemic. The hope is that the money paid to artists goes directly back into the community to keep it running. “The multitude of stories can help our community navigate their everyday lives, knowing that they are not alone and have shared experiences, struggles or accomplishments,” says Ed Marszewski, QT’s editor in chief. “It can show instances of solidarity, sadness, despair, and sometimes joy.”

It’s hard to know for sure how we’ll remember this moment. Most of us will certainly go back to the quarantine: how we lost our jobs and had trouble buying what we needed at the supermarket. Some of us will be reminded of losing a friend or someone in our family to the virus, or how we survived it. Learning the stories that are often overlooked in times of crisis opens up new memories to remember, and new ways of remembering them. It may be a small piece of the history of this moment, but I would argue not an insignificant one.

¤

Photographs by Sora Yamahira/Bellvisuals.com.

¤

LARB Contributor

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2020%2F04%2FDSC00266.jpg)