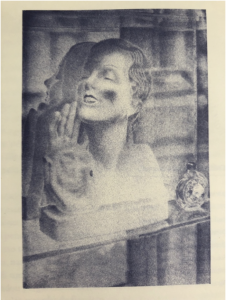

Ana Cristina Cesar (left); Bia Wouk (right).

Photos by João Almino.

There is a dress that my sister and I fell in love with as kids, a dress that used to be my mother's when she was in her 20s. For a while it was too big to fit me, so I used to watch my sister glide around the house in it, looking taller, elegant, and adult. Growing up, I marveled at a photograph we kept at home of my mother, wearing this dress on a blissful summer afternoon on a veranda. I think it represented for me womanhood itself: beautiful, at ease, free. I think it is why, when I was getting ready to leave home and move to college, I wanted to get the dress hemmed and take it with me.

Recently, I've been looking frequently at this photo, taken by my father, next to another photo he took just a year prior, in 1979: it shows the famous Brazilian poet Ana Cristina Cesar, known as Ana C., wearing the same dress and casting a similarly languid pose as my mother. She is sitting on the floor, the light a raspberry yellow and the dress crumpled around her legs. Sometimes people collect objects that once belonged to the famous artists they admire; it’s probably less common to find that an object you’ve had all your life (and that now hangs in your closet) was once worn and loved by that very artist.

¤

It wasn’t until I left home that I realized the scale of Ana C.’s renown, and still later that I’d be compelled to translate her. Growing up I had heard stories about her, but more so as a cherished and brilliant friend than the cult writer she would become.

My parents first met Ana C. at the Gare du Nord in Paris in 1979. She had arrived from England, where she was living at the time, studying literary translation at the University of Essex. They did not personally know her but had friends in common, who’d asked them to drive to the station. My mother, a Brazilian visual artist named Bia Wouk, vaguely remembers Ana C. sitting in the back of the car and saying something about The Police in a British accent. Not long after the drive, which was followed by dinner, they became good friends. Ana C. returned to Paris a few more times after that; she became enchanted with the city. She went to parties at my parents’ apartment. She went to my mother’s hairdresser, Gérard, and got the same short haircut. My mother even picked out the bright pink Yves Saint Laurent lipstick that Ana C. is wearing in the photo my father took.

The image is part of a series of photos that my father made of Ana C. in several outfits at his apartment. She was mortified when she saw the photos, writing to a friend in Brazil: “I received some scary portraits of mine from Paris, me posing in a dress and makeup like the mother in Pretty Baby, all of a sudden an older woman, looking like someone who hobbles.”

There are many photos left behind of Ana C., taken by friends and family, and the differences across them are striking. The critic Heloísa Buarque de Hollanda, who was also Ana C.’s mentor and close friend, describes the remaining photos as records of her “400 personas.” As is the case with many women artists, it can feel like there’s an unfair obsession over Ana C.’s looks — something that frustrated her in reviews of her poetry that were overly fixated on her image. But to more discerning critics like Hollanda, the photos are an extension of Ana C.’s writing: Just as she liked to explore multiple voices and pseudonyms in her poetry, she seemed to try on various identities.

When I look at the photos, I also see something that many who lived through their 20s would recognize: the desire to play and experiment until you feel closest to yourself. The year I left for college and hemmed the dress, I also got bold bangs. There’s a photo of me posing in my new look at a bar, and perhaps like Ana C., when I look at this photo now, I see myself (endearingly) stepping into a part that didn’t quite fit.

¤

At the time that Ana C. met my parents, she was writing Kid Gloves, a book that at turns reads like a letter, travel journal, and diary entry as it follows a woman journeying through Europe. Ana C. called letters and diaries “the most immediate kind of writing we have.” Her previous book, The Complete Correspondence (1979), was comprised of just one long, fictional letter (addressed to “my dear” and signed off by “Júlia”). “Historically, women start writing there, in the sphere of the particular, the familiar, the strictly intimate. Women don’t go directly writing for a newspaper,” she told a classroom of students in 1983, explaining her affinity for diaries, letters, and journals.

Ana C. was broadly interested in what it might mean to write in a “feminine” way, which, in her view, didn’t necessarily depend on the author’s gender. Some “feminine” markers, she told her students, include thinking about “the interlocutor” and playing with the “unsaid” — hallmarks of her own writing. In her poetry, especially Kid Gloves, the narrator directly addresses pen pals, demanding faster and longer replies. In other moments, her poetry reads — in her words — like a “fake diary” with secrets you can’t crack. “You don’t find intimacy there. It escapes,” she said.

Ana C., who was queer, confronted female stereotypes, at turns embracing and rejecting them. In one moment the protagonist of Kid Gloves is working on a translation and in the next is “grooming” herself. The narrator deftly analyzes classical paintings and then wonders about being “the difficult woman.” After Kid Gloves was published in 1980, Hollanda wrote that it “intentionally draws on that which is rejected as a ‘woman’s universe’” with an almost sarcastic air. For instance, the book’s cover drawing features a mannequin with a raised hand in a window display beside a bottle of perfume; it is a drawing that my mother made in Paris and that Ana tinged pink for the book.

Photocopy of Bia Wouk’s drawing “Violettes Rêvées.”

I recently called Hollanda to ask her how she might introduce Ana C. to an American audience today. “She is the ‘daughter’ of Clarice,” Hollanda said, alluding to the great novelist and short story writer Clarice Lispector, whose books in recent years have exploded in the United States. Both women had the same impulse, “which is to discover: who am I? What are women?” (Both were also fascinated by psychoanalysis; Ana C., like Lispector, had a Lacanian therapist.) Ana C. first explored in Brazilian poetry what Clarice Lispector first explored in Brazilian fiction: the everyday life and mind of a woman. “She made a mark in feminine Brazilian poetry,” Hollanda said. “It’s a before and after.”

¤

Growing up, I knew that it was hard, for my mother especially, to speak about Ana C. — Ana committed suicide just four years after they met, when she was back living in her native Rio de Janeiro. While I had previously contemplated translating her poetry, I quickly let go of the thought when I realized how painful it might be for my family to unlock their memories. Until one day, when visiting my mother in Brazil in the summer of 2018, she handed me a thick stack of letters. “Here, these are Ana’s letters,” she said. “You take them. I don’t have a use for them anymore.” I took my mother’s gesture as a sign to do something with them.

The two women never actually lived in the same city. Most of their friendship matured and unraveled over letters, which my mother had kept for over thirty years and not read since. They were all immaculately preserved (not exactly a surprise — the dress that she and Ana C. wore is also in impeccable condition). Many of the letters were written on thin sheets of lilac, yellow, and baby blue paper, which my mother had bought for her in Paris. One of them, I’d discover, was an early draft of a section in Kid Gloves, which obliquely describes one of my mother’s window display drawings of “three ducks trapped in a shop.” Kid Gloves is Ana C.’s most visual book, filled with references to art and meditations on the differences between writing and drawing. As the letters suggest, this was significantly influenced by her friendship with my mother.

Here was actual evidence that Ana C. was using letters to develop her poetry. Stylistically, they hold a lot in common: they are deliciously meandering, moving swiftly from sophisticated observations on paintings to descriptions of bike rides and punk haircuts and “Ain’t Misbehavin’” playing in the background. But the running thread that stands out to me is this performance of womanhood and becoming oneself. Ana C.’s letters, like her poetry, are about the piecing together of a life: as woman, writer, lover, friend, translator, daughter. She speaks of balancing her writing with a full time job. She wonders if she should pursue academia. She wants her “own little house.” In the meantime, she publishes incisive criticism, takes on ambitious translation projects, including The Hite Report on Male Sexuality, and writes her most influential collection of poetry, At Your Feet, published to acclaim in 1982. In a letter, she tells my mother that she initially wanted to call the book I’m Tired of Being a Man. In another letter she states, “I’m neither a lady nor a modern woman” — a line that then shows up in the poem “Lock and Key” in At Your Feet.

Who am I? What are women? Surely these are lifelong and unanswerable questions, but Ana C. seemed to be getting closer to their answers toward the end of her brief life. In a letter from December 24, 1981, she shares, “Something did click in my mind: it clicked to, yes, go after desire.” Her book, she says, “speaks of this: of desire that’s no longer tortured.”

¤

Translating Ana C. has been the most personal translation project I’ve ever done. Having some access to her life has made it tempting to read the person into the words. But I remind myself that her poetry, like her letters, are constructed and fascinating pieces of writing in and of themselves. Both are a kind of performance — “the poet is an imposter,” she wrote in a 1977 essay. Literature plays with “pretense to be able to speak.” I wonder if that was what she was doing when she posed for her photos as well — trying “to speak,” to say something new.

After my first year of college, I mostly stop wearing the dress, but I take it with me to each of my apartments. It isn’t until I discover the photo of Ana C. that I decide to try it on after years of neglect. Knowing that she had worn this exact dress 40 years earlier makes it more delicate in my hands, a rare artifact. At the same time, the original meaning it held for me is left intact. When I look in the mirror, the dress hugging me in all the wrong places, I am still dreaming of what being a grown-up could mean. I am looking at the idea of womanhood: fabricated, beautiful, unreal.

¤

Elisa Wouk Almino is a writer and literary translator from Portuguese. She is a senior editor at Hyperallergic and teaches translation and art writing at UCLA Extension and Catapult.

LARB Contributor

Elisa Wouk Almino is a writer and literary translator from Portuguese. She is a senior editor at Hyperallergic and teaches translation and art writing at UCLA Extension and Catapult.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2021%2F11%2FAna-Cristina-Cesar-and-Bia-Wouk-photos-by-Joao-Almino.png)