Bleeding Horizons: "Forrest Bess: Seeing Things Invisible"

By Travis DiehlNovember 24, 2013

Forrest Bess: Seeing Things Invisible by Clare Elliott

Triptych image: Richard Kraft, "Which Is To Say" (video stills)

Forrest Bess: Seeing Things Invisible

September 29, 2013 - January 5, 2014

Hammer Museum

10899 Wilshire Blvd, Los Angeles 90024

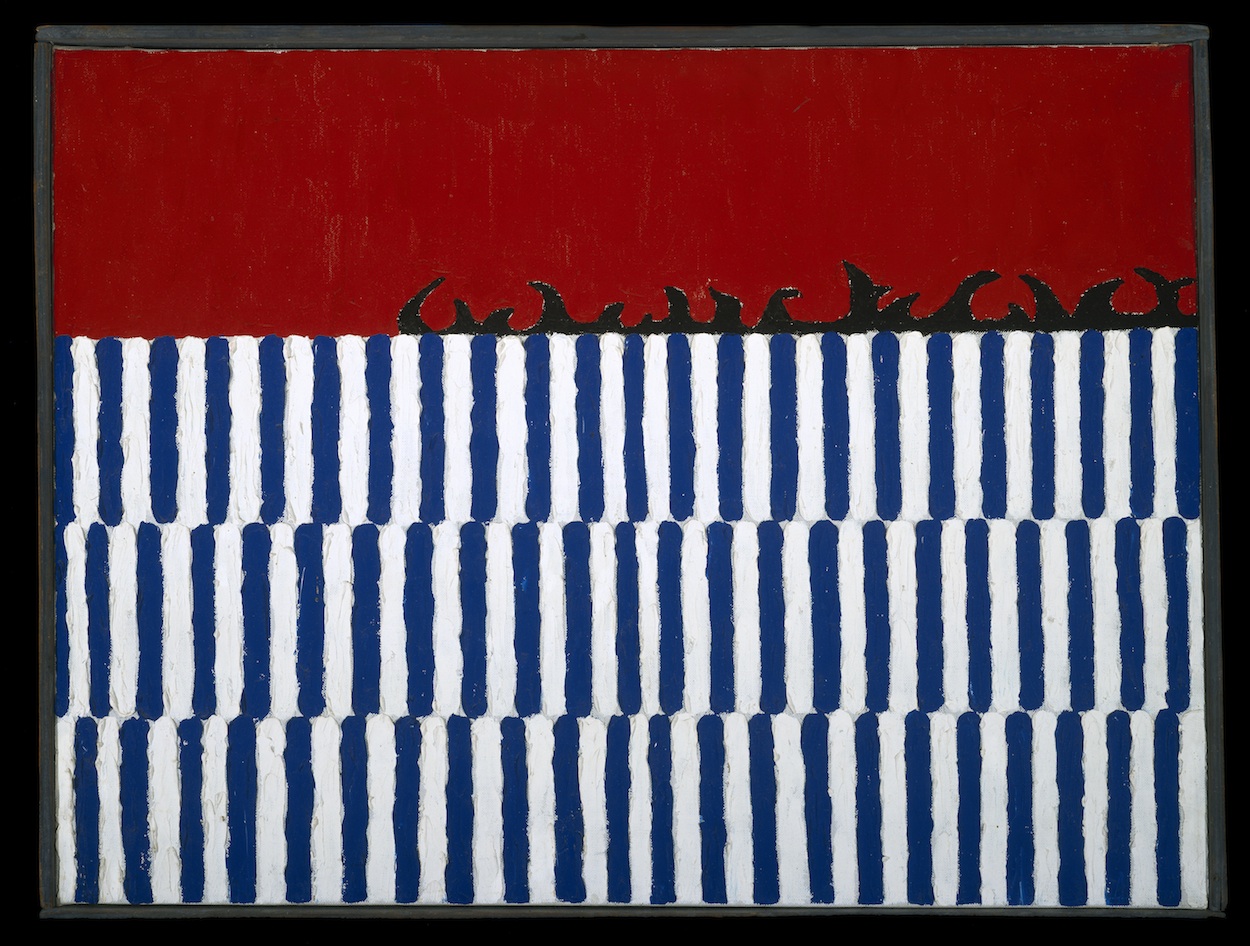

I would dare the critic who reviewed my work to sit at home some night just with one small insignificant canvas of mine — look at it and nothing else say for a period of thirty minutes or longer. I can make them cry for the loneliness they feel in the blue and white striped canvas.

– Forrest Bess, letter to Betty Parsons dated March 2, 1962

LIKE MANY OF FORREST Bess's paintings, Untitled (No. 11A), 1958, is an abstract land- or seascape crested by floating symbols. A shallow red field tops three rows of short vertical strokes of alternating blue and white paint. Curved black teeth or flames lick upwards along the right portion of the horizon. In one of his numerous letters, Bess describes his own attempt to decode this painting, seeing “above a red sky and dividing the stripes from the sky a thin jagged black line that I supposed was a beach with driftwood.” Bess would later begin to record these specific symbols in his writing; a “Primer of Basic Primordial Symbolism” is included both on one wall at the artist’s current exhibition at the Hammer Museum and in the back of the accompanying catalogue, compiling what Bess saw as an ancient, rediscovered vocabulary. There we learn the black flames are craters; the tick marks denote time passing; the parallel lines suggest the back and forth of intercourse or masturbation.

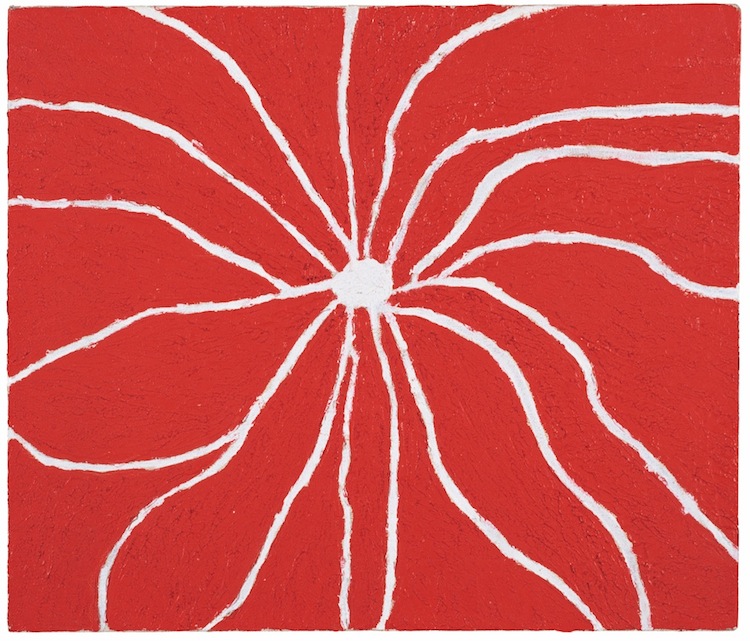

“The peninsula is a lonely, desolate place,” Bess wrote, “but there is something about it that attracts me to it — even though I am afraid of it.” The spread in the catalogue separating curator Clare Elliott's essay from plates of Bess's paintings is a monochrome blue photo of a marshy beach; the word artworks is set over the water. Perhaps the most romantic element of Bess's biography is his attachment to the sea — to the primal and essential and unknowable forces always lapping at the edge of the land as if eroding the rational. It was during his 27 years at Chinquapin Bay, staring all day at the water and sky as he fished for bait, painting at night, that Bess made most of his visionary work. He organized his symbolism along boundaries: between ground and sky; subterranean and celestial; interior and exterior. In Untitled (No. 5), 1949, a thick gradient of emerald to seafoam green surrounds a gray crag jutting from the left edge of the canvas. A violent orange peninsula slices from bottom to center, as if to touch the land. Four pieces of dark, gnarled wood frame the painting. The corners are unmitered, as Bess preferred. He constructed most of his own frames like the jambs of crude windows, just as he built his own house on the Gulf Coast of Texas from pieces of old boats. Untitled (The Spider), 1970, one of Bess's last paintings, depicts a white hole radiating white creases or scratches through textured, meaty red. The image is spider, sun, sphincter — female variegating male. This composition appears on the cover of the catalogue for Forrest Bess: Seeing Things Invisible, while The Spider's gray handmade frame matches the gray book cloth of the catalogue's spine. The unbleached craft paper chosen for the front and back endpapers hints at the raw, symbolic nature of the intervening pages, as if framed by Bess.

The blue and white stripes of (No. 11A), bounded by a thin slate gray frame, take on the scope of a striated ocean — a symbolic depth. Yet this image does not flash onto our mind's eye, or appear without context; we see (No. 11A) already informed of the dualities running like ribs through Bess's oeuvre: abstraction underpinned by hidden symbolism; the paintings set against the artist's biography; the rational beset by the irrational. The show’s co-curator, artist Robert Gober, remarks that the symbols make the paintings “uncomfortable”— transforming these bold, colorful, compact works into evidence of metaphysical delusions. How we read works such as (No. 11A) depends on what information we admit into our contemplation of the striped canvas — or else, what information we reject, once given. Curators Gober and Elliott, as well as Menil Collection director Josef Helfenstein, open their catalogue contributions with remarkably similar outlines of Bess's life. Elliott in her fourth sentence lists “his visions, his homosexuality, his theory of hermaphroditism, and both the symbolic system and the alarming experiments in self-surgery that resulted from these.” In his first line, Gober states that “Forrest Bess lived a life of profound poverty and solitude.” The present curators are not alone; introducing a 1981 Whitney exhibition of his work, Barbara Haskell wrote that Bess felt “a polarization manifested in the sensitive, gentle painter on the one hand; the rugged, liquor-drinking fisherman on the other.” All quickly note, however, that Bess exhibited with Betty Parsons in New York, and carried out extensive written correspondence with, among others, art historian Meyer Schapiro and psychoanalyst Carl Jung. This consummate outsider lived in a fishing shack in Texas while exhibiting no less than six times at what was then the most advanced insider gallery of the day, sharing a roster with the likes of Pollock and Rothko. Here, as elsewhere, Bess floats between two determinant poles.

¤

Forrest Bess died of a stroke in 1977. By 1982, his retrospective at the Whitney had been widely reviewed. Critics at the time recognized both the “contemporariness” of his small, expressive paintings — as well as an overbearing emphasis on his life story. 30 years later, perhaps sensing a greater cultural tolerance for the graphic details of transsexual operations, Elliott and Gober deliver a more complete account of Bess's theories, his self-surgery, his symbolism, and his frustrated homosexuality, offering related materials in three vitrines and quoting at length from Bess's letters. Seeing Things Invisible relates a heretofore “repressed” anecdote, for example, in which Bess, while in the Army Corps of Engineers, made a drunken pass at another enlistee and was beaten with a lead pipe; this skull injury supposedly heightened the frequency and intensity of the visions he had experienced since childhood. Still, the show foregrounds Bess's life in the catalogue and wall texts without claiming to provide a comprehensive biography. The task of a proper historicization is left to others, such as an article in the June 1982 Texas Monthly, which is open to its first page in one of the vitrines. As Thomas Lawson wrote in 1982, reviewing the Whitney show for Artforum: “It seems to me that if critics and historians are going to use biography to help them explain an artist's work they have an obligation to go all the way, not just tease their readers with fragmentary gossip.” Indeed, even as they fill in the gaps of a rough-hewn life, the curators' inclusions do more for our lurid fascination than for our understanding of Bess's art.

Bess believed a large urethral incision at the base of his penis would lead to the unification of the conscious and subconscious mind, and therefore to immortality. He developed his research in his “thesis,” a sourcebook of photos, diagrams, and diverse and often incoherent texts, which he sought unsuccessfully to display alongside his paintings. Only three pages of the actual thesis remain; the original was lost in the mail during Bess's lifetime. Still, the painter's expressed desire to exhibit his thesis seems to have been permission enough to introduce, in its absence, a range of ephemera. “This project of exhibiting material about his thesis along with the paintings aims to fulfill his wish,” Gober writes. Gober has reserved one vitrine for information on Bess and his self-surgery, including a letter from Bess to President Eisenhower; another with texts and photos relating to Betty Parsons; and a third containing books and articles by Dr. John Money, the discredited pioneer of sexual reassignment surgery, with whom Bess corresponded and who covered his case in a medical journal. Admittedly, like immortality achieved through hermaphroditism, exhibiting a missing text is a tall metaphysical order, while, on the other hand, to ignore this aspect of the paintings would have seemed like censorship. “One attempts to avoid stereotyping Bess as a mad genius,” writes Elliott — “to recognize the theories as a major underpinning of his work and acknowledge the surgeries, and the frightening element of self-harm, without allowing all of this to overwhelm the paintings themselves.” But how to remain respectful when the nature of representation in this instance is so gory? Bess considered his thesis a work of great scientific value — a seriousness hardly extended by the present curators (or, for that matter, by nearly anyone). As with the paintings, the portrayal of Bess's often insane ideas renders Seeing Things Invisible uncomfortable; seductive abstractions turn to viscera and blood.

¤

Bess insisted on the difference between visions — which he called “a kind of cultivated seeing into the darkness,” “ideograms,” and “inward sight”— and mere hallucinations. Unlike his contemporaries, Bess did not “experiment” on canvas. Instead he maintained that his paintings were faithful records of his visions, transcribed from sketches made immediately after they occurred. Bess compared his process to painting what one sees on the inside of the eyelid. Yet his unschooled technique, while idiosyncratic, was not naïve. Bess took basic painting lessons at an early age, studied architecture in college, spent the pre-war years in provincial artist communities, and was enough of a draftsman to earn a position designing camouflage for the military. He also knew art history. His 1951 Homage to Ryder is a clear statement of influence. Included in Seeing Things Invisible, the painting becomes another touchstone for the Bess myth — as the painter Albert Pinkham Ryder (1847–1917) was himself considered self-taught, an outsider and a recluse, despite considerable critical attention during his lifetime. Bess's Dedication to Van Gogh, 1946, dominated by zig-zagging pine green and orange furrows, echoes Wheatfield with Crows, 1890, which has a disputed provenance as one of the Dutch artist's final paintings. We find other parallels to Bess in Van Gogh's madness (also visionary), his self-mutilation (born, like Bess's, from unrequited desire), his alcoholism (including absinthe-induced hallucinations), his many letters to his brother (which constitute, as with Bess, our main biographical source), and his isolation in the countryside. Bess seems to have recognized, and even encouraged for himself, the position of the secluded, tortured artist — separated from a society that he felt misunderstood the true nature of his work.

Of course, Bess often could not make sense of his own visions. Yet the titles he gave to a few of the paintings suggest a skeleton of interpretation. The artist's symbology is presented in Seeing Things Invisible with the qualification that it is incomplete, inconsistent, and ultimately an unreliable way to interpret his work. Bess fitted one painting with two sets of hanging hardware; vertically, it bears the title Tree of Life; horizontally, the image becomes Sign of the Hermaphrodite. Indeed, Bess's paintings are a remarkably honest, naked example of painterly solipsism. The exhibition's title, Seeing Things Invisible, read one way, implies a mystical second sight; read another, Bess sees things that are simply not there.

Still, a certain curatorial ambiguity entertains the painter's more mystical, unscientific ideas. The metallic virus cresting the black horizon in The Prophecy (Sputnik), 1946, apparently titled after the Russian satellite's launch in 1957, suggests that Bess's primitive forms offer clues to the future. Perhaps there is a universal code to the subconscious; and maybe Bess's bizarre self-surgery, if fully realized, would have resulted in immortality. No one seems to subscribe to Bess's convoluted philosophy. Yet with critical distance, Gober and Elliott leave it to Bess's correspondents to unequivocally reject the scientific value of his thesis. Responding to Bess's request to exhibit his thesis alongside his paintings, Parsons somewhat patronizingly suggested he “show [his] paintings and the thesis in a medical hospital.” Carl Jung ultimately deemed Bess's discovery to be of the sort “found possibly once each century since the beginning of time.” “In the end,” wrote Dr. Money, “[Bess's] theory remained without support or substantiation, and so earned the classification not of a belief, but a delusion.”

Despite Bess's best efforts, visual art and medicine remain distinct disciplines. Yet whether or not his thesis is art is another question. In culture at large, Bess's visionary methods are in sync with a cyclical, resurgent interest in essence, in primitivism, and in alchemy. We recognize this tendency in the Neo-expressionism of the 1980s, when the trendiness that Bess so despised swung in his favor. “Working as an untutored loner,” Lawson wrote in 1982, “[Bess] still came up with the same old pictures,” as if all abstract-expressionist roads lead to the same vague symbology — a statement characteristic of the heady years of the “painting wars.” Bess started painting at another such moment in the mid-1940s, when it was as common for an artist to be influenced by Jung as by the perceived primitivism of African masks. It is unclear if Parsons aligned Bess with Abstract Expressionism or with the “originary” art she also showed. In the 2013 catalogue, Gober writes, “[Parsons] was devoted to American abstract art, but continued to show the art of ancient and primitive cultures, believing that these disparate works shared a formal and spiritual source.” Seeing Things Invisible, preceded by the miniature Bess exhibition that was Gober's contribution to the 2012 Whitney Biennial, comes at a moment when painting is again re-mystified, allowed a certain quasi-visionary status, and returning to self-containment. The Hammer's own 2012 Made in L.A. Biennial, which opened a few days after the Whitney show closed, provided several examples of this trend, with varying degrees of irony — from Pearl C. Hsiung's foldout painting of surreally rainbowed waves, presenting a “pop” version of transcendence, to the carved and painted wood mandalas of Zach Harris, self-styled with visionary and “outsider” tropes. At the same time, painting in and of itself has come to symbolize a stubborn faith in certain aesthetic truths, to the point where we can speak of Bess's work in terms of a binary between symbols and simply paintings, as if one is not always some of the other.

Bess sought the state of pseudo-hermaphroditism: not the coexistence of male and female traits, but their union — and here his delusional quest for immortality parallels the descent of a clear artistic narrative into the gruesome, ambivalent dialectics of postmodernism and beyond. Even as Bess's paintings are characterized by contrast and simplicity — paint straight from the tube, often knifed on, bold and optical juxtapositions of color, organic yet clear forms — they signify the dissolution of binaries; white in red; female in male. For artist Ken Okiishi, writing in Artforum in 2012, Bess's paintings appeal to our ideas of the post-human; he recuperates Bess as a prophet of biological art, working where technology meets the flesh. (Crucially, post-human modification will be elective — a choice that not all of us will make.) Indeed, the malleability or customization of the body as art has been both theorized and more or less legitimated in the past 50 years. Today we also see Bess's work with the benefit of developed gender-identity discourses. The present curators nominate Bess as a transgender martyr — lost within himself at a time when society offered no context or support for his desires — implying that we are beyond, or are ready to move beyond, that repressed state.

Yet Bess's isolation might also appeal to a Luddite anxiety in an era when connectivity is an essential part of culture, and outsider artist is practically an oxymoron. The embrace of abstract, personal paintings becomes an anti-intellectual stance — cut with the language of scholarship, but nonetheless unable to resist the sordid details of Bess's life, including his projections into metaphysical landscapes. Like Bess's thesis, the curatorial rhetoric of Seeing Things Invisible is not a clinical or distant portrayal but itself a muddied, “artistic,” personal endeavor. Divorced from the language of the subconscious, drifting between ignorance and knowledge, Bess's lonely and unrequited search for meaning parallels our own. Our neat phraseology of binaries, positive and negative, male and female, exterior and interior, bleeds into impossible continuums; we struggle to find symbols, ancient or new, for an indeterminate reality. The artist Forrest Bess is himself one such symbol. The Gulf Coast horizon, after all, is often muggy; gray; a liminal smear.

¤

Travis Diehl lives in Los Angeles. He edits the artist-run journal of art Prism of Reality.

LARB Contributor

LARB Staff Recommendations

Feelings and Forms: Jill Bennett’s "Practical Aesthetics"

Triptych image by Alfredo Jaar IN HIS 1913 ESSAY, “Art and Significant Form,” the art critic and Bloomsbury Group affiliate Clive Bell...

Surrealist Afterlives: On LACMA’s “In Wonderland”

Dorothea Tanning, Birthday, 1942 ON JANUARY 15, 1943, the New York Sun’s chief art critic, Henry McBride, explained precisely why it was women...

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!