GIVEN SOME of the emotionally troubling events that have closed out 2016, it may seem insensitive to suggest that an audience spend nearly two hours reliving the aftermath of one of the worst natural disasters to hit a US city in recent memory.

But the Blu-ray release of Robert Mugge’s compelling 2006 documentary, New Orleans Music in Exile, offers more than just a reminder of how flooding in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina nearly ended musical traditions that had survived in the city for centuries — destroying the homes of countless musicians and scattering them to all corners of the country.

It also highlights what is truly at stake when systems set up to protect and rescue people in national emergencies fail so spectacularly. The risk isn’t just to lives and property — though that should be enough. As Mugge’s intimate, far-reaching film illustrates, the soul of a community can be ripped apart by such disasters, erasing the progress made by those who have chosen to keep musical and cultural traditions alive for today’s generation and beyond.

Filmed over a couple of weeks just two months after the flood, New Orleans Music in Exile doesn’t spend much time on the question of how floodwaters breached the city’s levees. Nor do viewers get chapter and verse on the circumstances of the botched government response that led to agonizing days of deprivation for trapped residents.

As the filmmaker noted in a first-person piece for the streaming website Night Flight, when they were shooting the documentary, they were already aware Spike Lee was assembling a more politically incisive documentary film on the subject for HBO, and they chose instead to focus their piece on music and culture.

The result is a haunting, exhaustive retelling of the devastation musicians faced in the aftermath of Katrina and their efforts to cope with lives suddenly turned topsy-turvy. The primary subjects are the musicians who formed the lifeblood of the club scene in New Orleans: R&B singer Irma Thomas, British-born pianist Jon Cleary, trumpeter Kermit Ruffins, the Rebirth Brass Band, and others.

Premium cable channel Starz financed the film, premiered it in 2006, and released it on DVD several months later, Mugge said in an email. The filmmaker got the rights in June and included it among several of his films to be released on Blu-ray by the company MVD.

Stars like Dr. John and Cyril Neville make important appearances, but the meat of this story is the working-class players who kept the N’Awlins sound alive through clubs across the city.

Some of them were on tour elsewhere as the flooding erased their homes; others jumped into cars and trucks and fled to Baton Rouge, Memphis, Austin, or Houston with thousands of their fellow citizens. Regardless of the circumstance, once the floodwaters receded and the damage was clear, musicians faced an ominous question: what next?

In many ways, the story of New Orleans is the story of tribalism, how people from different countries, speaking different languages, formed an alliance that was sometimes uneasy, in light of the disparate histories involved. “New Orleans was never the Deep South,” percussionist/vocalist Cyril Neville tells Mugge’s cameras early in the film. “It was the northernmost part of the Caribbean.”

Indeed, as Neville noted in the film, the city’s wards have such deep, historic individual musical traditions that you could move from neighborhood to neighborhood and find that bands in each location performed a classic song like “Hey Pocky Way” a bit differently, though they all know the piece.

So what happens to that diverse yet coherent heritage, if many of the most ardent keepers of the flame are forced to move to Tennessee, Texas, Florida, or even further away?

Perhaps the biggest weakness of this Blu-ray — coming 11 years after the storm and 10 years after the documentary was first aired — is its lack of a postscript. The disc’s extras include an extensive interview with a public radio executive about rescuing several people by boat, a wonderful history of New Orleans piano styles by Cleary, and lots of additional or extended performances by musicians. But there is no follow-up footage to show us the current status of the people Mugge captured just months after many of them lost everything. Cleary, who is shown talking ruefully about struggling to get a refrigerator full of spoiled food out of his home, won a Best Regional Roots Music Grammy award this year for his record Go Go Juice.

Mugge’s cameras followed Thomas — often billed as “the soul queen of New Orleans” — as she sorted through the debris of the Lion’s Den, the club she owned with her husband. Viewers are told that the couple lost everything — their business, their cars, their home, their rental properties. But Thomas also bounced back in 2007 to win the first Grammy of her 50-plus-year singing career — Best Contemporary Blues Album for a disc titled, appropriately enough, After the Rain.

These are the kinds of success stories hinted at by the film’s ending, which shows Ruffin welcomed by clubs in Houston and other players finding refuge in Austin and Memphis. Dr. John closes out the film with a version of his anthem “Sweet Home New Orleans,” which sums up the feeling of those who want their old city back.

Several voices in the film wonder if the scattering of musical talent to other cities will turn New Orleans into a shell of its former self — a tourist trap propped up by superficial renderings of its storied musical history, while the true creators build lives elsewhere.

“The intensity of the music is going to be diluted,” warned Jan Ramsey, publisher of OffBeat Magazine. “One of the things that was really important about New Orleans was the music in generations of families. And they’re spread all over the place now.”

Several stories written for major media outlets commemorating the 10th anniversary of Katrina’s landfall last year indicated Ramsey’s worst-case scenario didn’t materialize — though a loss of black residents and a spike in gentrification has made retaining musical traditions more difficult.

Mugge wrote in an email that, given the expense of updating music rights, remastering, promotion, and other costs, it didn’t seem feasible to spend more dollars creating a mini-movie to follow up the 2006 story. Pianist Eddie Bo, shown in the film receiving a new portable piano financed by donations, died in 2009. But many other musicians from the film are doing well and most have moved back to the city, Mugge added. It seems there’s another wonderful documentary at hand, if Mugge ever gets the chance to answer many of the important questions his film raised more than a decade ago.

Certainly the best part of New Orleans Music in Exile is the music. Mugge, a documentarian known for revealing, music-oriented films on artists like Sun Ra and Gil Scott-Heron, gives lots of space for musicians like Dr. John, Cyril Neville, The Iguanas, Papa Grows Funk, and Marcia Ball to show off the sounds that have given New Orleans such a special place in history and in the public imagination.

The film’s beginning features violinist and vocalist Theresa Andersson delivering a haunting version of Neil Young’s “Like a Hurricane” in the studio, the ragged tones of her distorted violin providing an unsettling counterpoint to her ethereal vocals. Her work sets the stage for a range of performances that fill the movie — from members of the Rebirth Brass Band playing outside to Papa Grown Funk jamming at The Maple Leaf Bar and Dr. John working his Gris-Gris magic before a larger crowd, demonstrating the wide reach of New Orleans musical exports affected by the flood.

In February 2006, I spent time as a reporter in New Orleans, documenting how journalists’ struggle to recover at the Times-Picayune newspaper mirrored the struggle of the larger population to get back on their feet. At the time, I was amazed at how, five months after the flooding, there were still rows and rows of abandoned cars beneath highway overpasses, houses were still sitting in the middle of roads in residential neighborhoods, and the French Quarter still felt a bit like a ghost town.

There was, at the time, a muted but unmistakable spirit in the town, a sense of dedication to survive the disaster and get back to the business of life in New Orleans as soon as possible. That spirit also flowers in Mugge’s film, as musicians are shown rebuilding their lives one gig at a time, driven by the certain knowledge that saving their town and its musical heritage is worth every effort.

The flooding that devastated New Orleans left wounds that still haven’t fully closed. New Orleans Music in Exile provides poignant, bracing testimony to the history and heritage that the United States risks by underestimating what Mother Nature can do.

But the Blu-ray release of Robert Mugge’s compelling 2006 documentary, New Orleans Music in Exile, offers more than just a reminder of how flooding in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina nearly ended musical traditions that had survived in the city for centuries — destroying the homes of countless musicians and scattering them to all corners of the country.

It also highlights what is truly at stake when systems set up to protect and rescue people in national emergencies fail so spectacularly. The risk isn’t just to lives and property — though that should be enough. As Mugge’s intimate, far-reaching film illustrates, the soul of a community can be ripped apart by such disasters, erasing the progress made by those who have chosen to keep musical and cultural traditions alive for today’s generation and beyond.

Filmed over a couple of weeks just two months after the flood, New Orleans Music in Exile doesn’t spend much time on the question of how floodwaters breached the city’s levees. Nor do viewers get chapter and verse on the circumstances of the botched government response that led to agonizing days of deprivation for trapped residents.

As the filmmaker noted in a first-person piece for the streaming website Night Flight, when they were shooting the documentary, they were already aware Spike Lee was assembling a more politically incisive documentary film on the subject for HBO, and they chose instead to focus their piece on music and culture.

The result is a haunting, exhaustive retelling of the devastation musicians faced in the aftermath of Katrina and their efforts to cope with lives suddenly turned topsy-turvy. The primary subjects are the musicians who formed the lifeblood of the club scene in New Orleans: R&B singer Irma Thomas, British-born pianist Jon Cleary, trumpeter Kermit Ruffins, the Rebirth Brass Band, and others.

Premium cable channel Starz financed the film, premiered it in 2006, and released it on DVD several months later, Mugge said in an email. The filmmaker got the rights in June and included it among several of his films to be released on Blu-ray by the company MVD.

Stars like Dr. John and Cyril Neville make important appearances, but the meat of this story is the working-class players who kept the N’Awlins sound alive through clubs across the city.

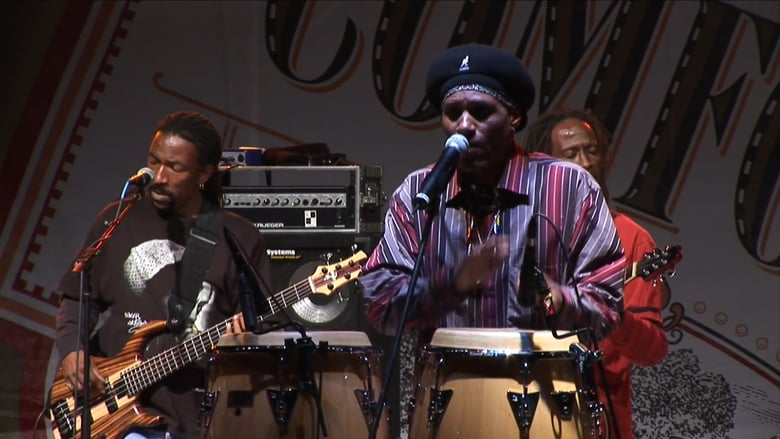

Cyril Neville and Tribe 13

Some of them were on tour elsewhere as the flooding erased their homes; others jumped into cars and trucks and fled to Baton Rouge, Memphis, Austin, or Houston with thousands of their fellow citizens. Regardless of the circumstance, once the floodwaters receded and the damage was clear, musicians faced an ominous question: what next?

In many ways, the story of New Orleans is the story of tribalism, how people from different countries, speaking different languages, formed an alliance that was sometimes uneasy, in light of the disparate histories involved. “New Orleans was never the Deep South,” percussionist/vocalist Cyril Neville tells Mugge’s cameras early in the film. “It was the northernmost part of the Caribbean.”

Indeed, as Neville noted in the film, the city’s wards have such deep, historic individual musical traditions that you could move from neighborhood to neighborhood and find that bands in each location performed a classic song like “Hey Pocky Way” a bit differently, though they all know the piece.

So what happens to that diverse yet coherent heritage, if many of the most ardent keepers of the flame are forced to move to Tennessee, Texas, Florida, or even further away?

Perhaps the biggest weakness of this Blu-ray — coming 11 years after the storm and 10 years after the documentary was first aired — is its lack of a postscript. The disc’s extras include an extensive interview with a public radio executive about rescuing several people by boat, a wonderful history of New Orleans piano styles by Cleary, and lots of additional or extended performances by musicians. But there is no follow-up footage to show us the current status of the people Mugge captured just months after many of them lost everything. Cleary, who is shown talking ruefully about struggling to get a refrigerator full of spoiled food out of his home, won a Best Regional Roots Music Grammy award this year for his record Go Go Juice.

Mugge’s cameras followed Thomas — often billed as “the soul queen of New Orleans” — as she sorted through the debris of the Lion’s Den, the club she owned with her husband. Viewers are told that the couple lost everything — their business, their cars, their home, their rental properties. But Thomas also bounced back in 2007 to win the first Grammy of her 50-plus-year singing career — Best Contemporary Blues Album for a disc titled, appropriately enough, After the Rain.

These are the kinds of success stories hinted at by the film’s ending, which shows Ruffin welcomed by clubs in Houston and other players finding refuge in Austin and Memphis. Dr. John closes out the film with a version of his anthem “Sweet Home New Orleans,” which sums up the feeling of those who want their old city back.

Several voices in the film wonder if the scattering of musical talent to other cities will turn New Orleans into a shell of its former self — a tourist trap propped up by superficial renderings of its storied musical history, while the true creators build lives elsewhere.

“The intensity of the music is going to be diluted,” warned Jan Ramsey, publisher of OffBeat Magazine. “One of the things that was really important about New Orleans was the music in generations of families. And they’re spread all over the place now.”

Several stories written for major media outlets commemorating the 10th anniversary of Katrina’s landfall last year indicated Ramsey’s worst-case scenario didn’t materialize — though a loss of black residents and a spike in gentrification has made retaining musical traditions more difficult.

Mugge wrote in an email that, given the expense of updating music rights, remastering, promotion, and other costs, it didn’t seem feasible to spend more dollars creating a mini-movie to follow up the 2006 story. Pianist Eddie Bo, shown in the film receiving a new portable piano financed by donations, died in 2009. But many other musicians from the film are doing well and most have moved back to the city, Mugge added. It seems there’s another wonderful documentary at hand, if Mugge ever gets the chance to answer many of the important questions his film raised more than a decade ago.

Certainly the best part of New Orleans Music in Exile is the music. Mugge, a documentarian known for revealing, music-oriented films on artists like Sun Ra and Gil Scott-Heron, gives lots of space for musicians like Dr. John, Cyril Neville, The Iguanas, Papa Grows Funk, and Marcia Ball to show off the sounds that have given New Orleans such a special place in history and in the public imagination.

The film’s beginning features violinist and vocalist Theresa Andersson delivering a haunting version of Neil Young’s “Like a Hurricane” in the studio, the ragged tones of her distorted violin providing an unsettling counterpoint to her ethereal vocals. Her work sets the stage for a range of performances that fill the movie — from members of the Rebirth Brass Band playing outside to Papa Grown Funk jamming at The Maple Leaf Bar and Dr. John working his Gris-Gris magic before a larger crowd, demonstrating the wide reach of New Orleans musical exports affected by the flood.

In February 2006, I spent time as a reporter in New Orleans, documenting how journalists’ struggle to recover at the Times-Picayune newspaper mirrored the struggle of the larger population to get back on their feet. At the time, I was amazed at how, five months after the flooding, there were still rows and rows of abandoned cars beneath highway overpasses, houses were still sitting in the middle of roads in residential neighborhoods, and the French Quarter still felt a bit like a ghost town.

There was, at the time, a muted but unmistakable spirit in the town, a sense of dedication to survive the disaster and get back to the business of life in New Orleans as soon as possible. That spirit also flowers in Mugge’s film, as musicians are shown rebuilding their lives one gig at a time, driven by the certain knowledge that saving their town and its musical heritage is worth every effort.

The flooding that devastated New Orleans left wounds that still haven’t fully closed. New Orleans Music in Exile provides poignant, bracing testimony to the history and heritage that the United States risks by underestimating what Mother Nature can do.

¤

LARB Contributor

Eric Deggans is NPR’s first full-time TV critic. He came to NPR from the Tampa Bay Times newspaper in Florida, where he served as TV/Media Critic and in other roles for nearly 20 years. A journalist for more than 20 years, he is also the author of Race-Baiter: How the Media Wields Dangerous Words to Divide a Nation, a look at how prejudice, racism, and sexism fuel some elements of modern media, published in October 2012 by Palgrave Macmillan.

Now serving as chair of the Media Monitoring Committee for the National Association of Black Journalists, he has also served on the board of directors for the national Television Critics Association and on the board of the Mid-Florida Society of Professional Journalists.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Après Katrina, Le Déluge

Gary Rivlin's "Katrina: After the Flood" argues that "Katrina was pretext for ridding New Orleans of enough blacks … so that whites were once again...

Katrina’s Bullets: Ronnie Greene on Police Violence

To read Ronnie Greene’s Shots on the Bridge in the time of Black Lives Matter is to confront rage.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2016%2F12%2FDeggansMugge.png)