The Online Pivot: California’s Cultural Institutions Adjust to the New Reality

By Sophia StewartJune 1, 2020

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2020%2F06%2FStewartVirtualEvfents.png)

I READ THE OTHER DAY that the experience of this pandemic has caused people to have strange and unusually vivid dreams. Reading this was a comfort — I thought it was just me. Since stay-at-home orders were first issued in March, I’ve been having this realistic recurring dream where I’m wandering around an unspecified museum — it’s something of a cross between the Getty Center and the Norton Simon — and admiring the art on the walls. It’s a little crowded, and the voices of fellow museumgoers echo around the gallery. When I wake up, I feel calm; then, after a moment of reorientation, crestfallen. All this to say: I think I really miss going to museums.

It’s been almost three months since every museum in California closed its doors to the public. As have most all of California’s other cultural institutions, including bookstores, performance venues, literary festivals, community centers, art galleries, and co-working spaces. I long for these places too — for the discoveries, the conversations, and the feelings of connectedness.

For obvious reasons, a ban on large gatherings was one of California’s first responses to the coronavirus pandemic, and, as Governor Gavin Newsom announced at a press conference in mid-April, the prospect of their being reauthorized “is negligible at best until we get to herd immunity and we get to a vaccine.”

Cultural institutions have been especially hard hit by these restrictions. In a survey conducted by the nonprofit Americans for the Arts, 11,000 organizations in the arts and cultural sector reported a combined loss of nearly $5 billion, as well as over 300,000 lost jobs. A third of respondents expect the pandemic to have a “severe” impact on their organization.

Yet cultural institutions haven’t given up, and have gotten creative in their efforts to maintain a presence in their communities. Many organizations have taken advantage of digital technologies like Zoom, Crowdcast, and YouTube to provide programming virtually. Over the last month, I’ve immersed myself in cultural programming by some of the state’s most valuable organizations: in Northern California, the Bay Area Book Festival and City Arts and Lectures; and in Southern California, the Hammer Museum, Inlandia Institute, and Women’s Center for Creative Work.

Since its inception in 2015, the Bay Area Book Festival has become one of the nation’s premier literary gatherings. I attended the weekend-long Festival in 2019, scuttling from venue to venue, attending talks and panels with writers like Morgan Parker, Kiese Laymon, R. O. Kwon, and Ishmael Reed, and grabbing the occasional iced tea in between. This year, the entire Bay Area Book Festival has moved online. “When we had to cancel on March 11, our entire program — 265 authors, 130 distinct programs — was ready to launch on our website for ticketing,” says Cherilyn Parsons, the festival’s founder and executive director. “So with what felt like a herculean effort, because we had to reinvent how we did almost everything, we pivoted to present a virtual festival: Bay Area Book Festival #UNBOUND.”

The #UNBOUND series launched on May 1 and will present weekly free programming through the end of the year. Programs debut and are recorded on YouTube Premiere, with a live audience chat feature. #UNBOUND offers an impressive array of talks with writers such as Garth Greenwell, Lidia Yuknavitch, and Adam Hochschild, as well as timely panel discussions. “We’ve focused the rollout of our virtual festival on topics with special relevance to our situation now, including voting rights, wellness, and parenting,” says Parsons.

The online pivot has been a mixed bag. Technology, Parsons says, has made author “appearances” more convenient, especially for international speakers. The switch also saved the festival money on travel expenses and venue rentals. But “converting to virtual programs is a tricky financial calculation,” says Parsons, and “we lost a lot more than we saved by canceling” in terms of ticket revenue, exhibitor fees, sponsorships, and donations. And “the huge downside to virtual programs is that people expect them to be free” — even though, as Parsons notes, “they’re not free to produce!”

Across the San Francisco Bay, City Arts and Lectures has been making the effort to reincarnate their cancelled conversation series online. The San Francisco–based nonprofit has hosted more than 50 annual lectures and conversations every year since 1980, usually at the historic Sydney Goldstein Theater. I’ve been lucky enough to attend several of City Arts and Lectures’s most exciting match-ups, from Hilton Als and Jelani Cobb to Emily Nussbaum and Raphael Bob-Waksberg.

Some months ago, I purchased a ticket to see two of my favorite writers, Jia Tolentino and Jenna Wortham, converse in a City Arts and Lectures talk. This past week, I attended their conversation — from the comfort of my bed, rather than the grandeur of the Goldstein. Since mid-March, City Arts and Lectures has made all of their talks webcast, streaming them on YouTube and making them free to the public. I’ve dropped in on a few especially interesting discussions — between Namwali Serpell and Carmen Maria Machado this past April, for instance — and I’ve been impressed by the intimacy of the conversations. With the artifice of the stage stripped away, it feels as though we are taking part in a virtual salon, with writers talking among themselves in their own homes and sharing ideas with each other, rather than presenting for an audience.

Tolentino and Wortham’s discussion was inevitably permeated by, but not limited to, pandemic talk. Verdant potted plants at their sides, they covered everything from surveillance capitalism to mutual aid to the Beyoncé remix of Megan Thee Stallion’s “Savage.” Tolentino also revealed a new tradition she’s started in quarantine: a Thursday-night club in which she and her friends watch movies together. The criterion for selection? They only watch movies “where they say the title of the movie dramatically in the movie.”

In both form and content, the conversation highlighted the possibilities as well as the limitations of human interaction in virtual space. “Nothing compares to actual presence,” Tolentino told Wortham. “These things are so wonderful but they are so wonderful because they remind us of how much we want to be with each other.”

Museums, literary institutes, and creative networks in Southern California have also been adjusting to social distancing restrictions. The Hammer Museum — one of my favorite places in Los Angeles — has been able to deliver most all of their regularly scheduled programming virtually. “Under these extraordinary circumstances,” says Director of Public Programs Claudia Bestor, “the Hammer is continuing to create spaces — now virtual — for our community to engage with art and ideas and also to find rest.” The Museum is hosting, for example, its weekly Mindful Awareness Meditation Sessions over Zoom, and is holding its annual Bloomsday — a presentation of James Joyce with staged readings of excerpts from Ulysses — online.

Every Wednesday at 12:30 p.m., as part of the Hammer’s Lunchtime Art Talks, a member of the museum’s curatorial department leads a short, free discussion about an individual work from the collection. Recently I joined a talk on Lorna Simpson’s “Backdrops Circa 1940s” (1990), led by curatorial assistant Vanessa Arizmendi. When I opened the Zoom link that had been emailed to me a few minutes prior to the event, I was surprised by the turnout — 180 attendees.

At the start, Arizmendi provided some tips and tricks for maximizing our Zoom experience, like using Speaker Mode and raising our hand in the Participants panel. Then she delivered an engaging presentation about Simpson, self-portraiture, and “Backdrops” itself. The work is stunning — a screenprint diptych on felt panels that places a photo of a young black woman lounging among the stars next to a photo of Lena Horne singing amid twinkling lights. As we look at one black woman posing in a photography studio and another performing on stage, we are made to examine our conceptions of glamour, and to ask ourselves whose images are worthy of reproduction.

Some 70 miles east of the Hammer, the Inlandia Institute in Riverside has produced a particularly robust assortment of online programming. I’d never before heard of the nonprofit literary center, and I was deeply moved by their mission to support literary activity in the Inland Empire, where arts and culture have been historically underfunded. “Given how suddenly our lives changed with the pandemic and the safer-at-home orders,” says Executive Director Cati Porter, “we — as an organization whose main focus has been to provide free public events and workshops in venues across the region — had to act quickly in order to preserve some of what we had to offer.”

Many of Inlandia’s writing workshops were able to swiftly move to a virtual format, thanks to flexible workshop leaders who have utilized a variety of technologies like Facebook groups, Zoom, and Google Classroom. Inlandia decided to offer its fee-based workshops for free, “in acknowledgment of how the pandemic has affected many of our network’s members,” says Porter. The Institute has also been able to move many of its public events — including public readings and a live storytelling series called The Flame — online by broadcasting them on YouTube.

Inlandia Books, the Institute’s publishing arm, is also launching at least two new books virtually. One of them, San Bernardino, Singing, is an anthology of work by Inland writers edited by poet and educator Nikia Chaney. Through Inlandia’s Facebook events page, the Institute has serially released author readings, book giveaways, and special live author events. I’ve been particularly impressed with Inlandia’s social media savvy, as their Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter have been bustling ever since their physical location closed its doors.

Like the Bay Area Book Festival, Inlandia has hit rough spots along the way. “There are of course certain inherent challenges to holding virtual events, technology being a major one,” says Porter. “In addition to holding the events, we’ve also had to coach presenters on lighting, camera positioning, backgrounds, and engaging with the audience by looking and speaking directly into the camera — something that doesn’t come easily for many of us!” But the new configurations have also provided some unexpected benefits. “I can’t say that it’s been easy, but I’m happy that we’ve been able to quickly transition,” Porter says, “and in many cases our audience has grown because there are fewer competing events and we can reach outside of the confines of a commute.”

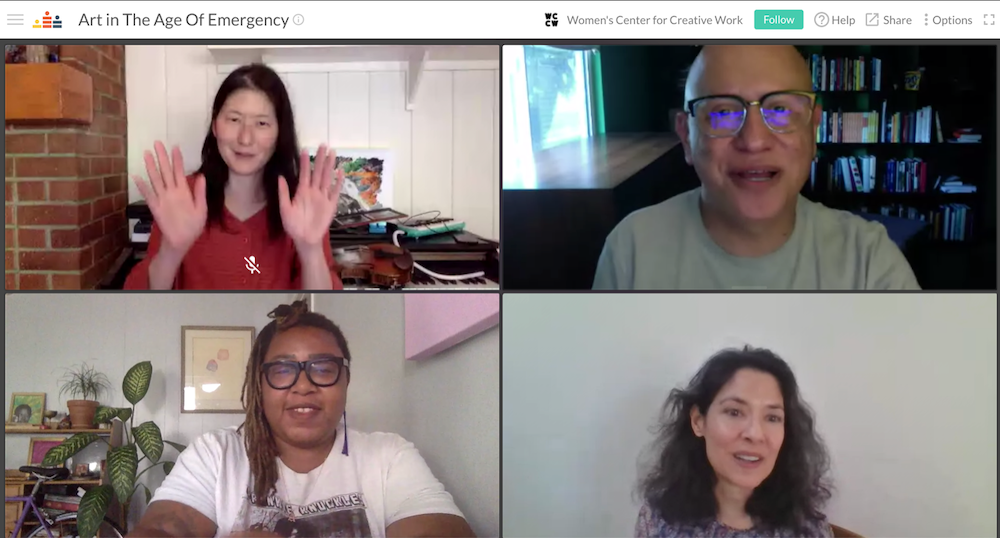

The Women’s Center for Creative Work (WCCW), headquartered in Los Angeles’s Frogtown, has also swiftly moved many of its regular events and services online, now facilitating digital workshops and co-working sessions. Founded in 2013, the Center serves as a space for connecting L.A.’s feminist creative communities. I attended their digital discussion titled “Art in the Age of Emergency,” which was organized directly in response to our present moment. In front of nearly 70 attendees, moderator Yxta Maya Murray and panelists Alex Espinoza, Kathleen Kim, and Adee Roberson spoke about collective grief and mourning, what it means to be “essential,” the articulative power of art, the relationship between art and action, and the significance of race, class, ethnicity, and migration in conversations around COVID-19.

I was particularly struck by the smoothness of the Crowdcast presentation. Usually, remote events make me anxious — accidentally unmuted mics, videos freezing, a general uncertainty about who should talk when. But this time changes between different screens and speakers were seamless and aesthetically pleasing. It was also interesting to see these artists in their respective domestic spaces: Roberson, a visual artist, with paintings on her walls; Kim, a musician, with a piano behind her, melodica perched on top; and Espinoza, a writer, with bookshelves brimming.

Prior to the group discussion, each artist had a one-on-one conversation with Murray about how they’ve responded to COVID-19 in their practice and in their lives. Then each presented a work of art. Roberson first discussed her use of the quarantine as “generative time,” devoted not to making new work, but to research, reading, and relaxation. Now is a time for “processing and input,” she said, not necessarily productivity. Then she shared “we speak light,” an evocative three-minute video presentation. During the short film we see a pair of outstretched arms reaching for a crisp blue sky, waves crashing on a palm tree-spotted shoreline, sun streaming through green palm leaves, and figures in veiled baseball caps. It was both nostalgic and uncanny — while I longed for the summer sights that I know we won’t be able to enjoy this year, I also recognized that the facial coverings of the veiled figures were not unlike the ubiquitous face masks I see during my daily walks.

Next, Espinoza admitted that he has found it difficult to write during this time, “yet at the same time my work feels more urgent.” He’s felt especially challenged by the lockdown because “as writers, we need to participate with the world.” But he is determined to press on: “We’re passing through this period of trauma together,” he said. “That’s what art does — we have to look at the difficulty in order to shed light on it and understand what’s happening.” Then he read an excerpt from his novel-in-progress, which follows a group of strangers from different backgrounds dealing with various forms of loss — familial, personal, spiritual, and psychological. It’s about “collective grief,” Espinoza said in introducing the work, about “grief less as a private experience and more as a communal experience.”

Finally, Kim shared her feeling that the pandemic has “revealed our collective precarity,” and in fact exposes an entire “future of precarity.” Then she played an original composition that she said “contemplates the multiple meanings of the world ‘slur.’” A slur, Kim explained, has many definitions — a musical term, a euphemism for a racial insult, and a descriptor of speech. Throughout the song, Kim used the entirety of her violin, tapping on its body, plucking its strings, bowing, skidding. There was a fascinatingly “fractured aspect to the music,” Murray commented. Most interestingly, Kim used a looping pedal to play on top of her own bowing and also vocalize into a headset microphone. It sent chills up my forearms.

Last night I had my museum dream again. I realize now it’s not really about museums — it’s about a yearning for shared spaces, communal experiences. It’s about wanting to go somewhere, to learn something, to see or hear the new and the nourishing. Even now, under quarantine, California’s most important cultural institutions are committed to feeding that need. I think more and more about something Alex Espinoza said during the talk at WCCW: in a moment like this, the role of art — and, more broadly, of culture — is to “try to make us feel connected while we are disconnected.” With a spirit of resilience and a sense of creativity, curators, workshop leaders, and artists of all stripes have done just that.

Sophia Stewart is a writer, editor, and cultural critic from Los Angeles. You can find her writing here and follow her on Twitter @smswrites.

It’s been almost three months since every museum in California closed its doors to the public. As have most all of California’s other cultural institutions, including bookstores, performance venues, literary festivals, community centers, art galleries, and co-working spaces. I long for these places too — for the discoveries, the conversations, and the feelings of connectedness.

For obvious reasons, a ban on large gatherings was one of California’s first responses to the coronavirus pandemic, and, as Governor Gavin Newsom announced at a press conference in mid-April, the prospect of their being reauthorized “is negligible at best until we get to herd immunity and we get to a vaccine.”

Cultural institutions have been especially hard hit by these restrictions. In a survey conducted by the nonprofit Americans for the Arts, 11,000 organizations in the arts and cultural sector reported a combined loss of nearly $5 billion, as well as over 300,000 lost jobs. A third of respondents expect the pandemic to have a “severe” impact on their organization.

Yet cultural institutions haven’t given up, and have gotten creative in their efforts to maintain a presence in their communities. Many organizations have taken advantage of digital technologies like Zoom, Crowdcast, and YouTube to provide programming virtually. Over the last month, I’ve immersed myself in cultural programming by some of the state’s most valuable organizations: in Northern California, the Bay Area Book Festival and City Arts and Lectures; and in Southern California, the Hammer Museum, Inlandia Institute, and Women’s Center for Creative Work.

¤

Since its inception in 2015, the Bay Area Book Festival has become one of the nation’s premier literary gatherings. I attended the weekend-long Festival in 2019, scuttling from venue to venue, attending talks and panels with writers like Morgan Parker, Kiese Laymon, R. O. Kwon, and Ishmael Reed, and grabbing the occasional iced tea in between. This year, the entire Bay Area Book Festival has moved online. “When we had to cancel on March 11, our entire program — 265 authors, 130 distinct programs — was ready to launch on our website for ticketing,” says Cherilyn Parsons, the festival’s founder and executive director. “So with what felt like a herculean effort, because we had to reinvent how we did almost everything, we pivoted to present a virtual festival: Bay Area Book Festival #UNBOUND.”

The #UNBOUND series launched on May 1 and will present weekly free programming through the end of the year. Programs debut and are recorded on YouTube Premiere, with a live audience chat feature. #UNBOUND offers an impressive array of talks with writers such as Garth Greenwell, Lidia Yuknavitch, and Adam Hochschild, as well as timely panel discussions. “We’ve focused the rollout of our virtual festival on topics with special relevance to our situation now, including voting rights, wellness, and parenting,” says Parsons.

The online pivot has been a mixed bag. Technology, Parsons says, has made author “appearances” more convenient, especially for international speakers. The switch also saved the festival money on travel expenses and venue rentals. But “converting to virtual programs is a tricky financial calculation,” says Parsons, and “we lost a lot more than we saved by canceling” in terms of ticket revenue, exhibitor fees, sponsorships, and donations. And “the huge downside to virtual programs is that people expect them to be free” — even though, as Parsons notes, “they’re not free to produce!”

Across the San Francisco Bay, City Arts and Lectures has been making the effort to reincarnate their cancelled conversation series online. The San Francisco–based nonprofit has hosted more than 50 annual lectures and conversations every year since 1980, usually at the historic Sydney Goldstein Theater. I’ve been lucky enough to attend several of City Arts and Lectures’s most exciting match-ups, from Hilton Als and Jelani Cobb to Emily Nussbaum and Raphael Bob-Waksberg.

Some months ago, I purchased a ticket to see two of my favorite writers, Jia Tolentino and Jenna Wortham, converse in a City Arts and Lectures talk. This past week, I attended their conversation — from the comfort of my bed, rather than the grandeur of the Goldstein. Since mid-March, City Arts and Lectures has made all of their talks webcast, streaming them on YouTube and making them free to the public. I’ve dropped in on a few especially interesting discussions — between Namwali Serpell and Carmen Maria Machado this past April, for instance — and I’ve been impressed by the intimacy of the conversations. With the artifice of the stage stripped away, it feels as though we are taking part in a virtual salon, with writers talking among themselves in their own homes and sharing ideas with each other, rather than presenting for an audience.

Tolentino and Wortham’s discussion was inevitably permeated by, but not limited to, pandemic talk. Verdant potted plants at their sides, they covered everything from surveillance capitalism to mutual aid to the Beyoncé remix of Megan Thee Stallion’s “Savage.” Tolentino also revealed a new tradition she’s started in quarantine: a Thursday-night club in which she and her friends watch movies together. The criterion for selection? They only watch movies “where they say the title of the movie dramatically in the movie.”

In both form and content, the conversation highlighted the possibilities as well as the limitations of human interaction in virtual space. “Nothing compares to actual presence,” Tolentino told Wortham. “These things are so wonderful but they are so wonderful because they remind us of how much we want to be with each other.”

¤

Museums, literary institutes, and creative networks in Southern California have also been adjusting to social distancing restrictions. The Hammer Museum — one of my favorite places in Los Angeles — has been able to deliver most all of their regularly scheduled programming virtually. “Under these extraordinary circumstances,” says Director of Public Programs Claudia Bestor, “the Hammer is continuing to create spaces — now virtual — for our community to engage with art and ideas and also to find rest.” The Museum is hosting, for example, its weekly Mindful Awareness Meditation Sessions over Zoom, and is holding its annual Bloomsday — a presentation of James Joyce with staged readings of excerpts from Ulysses — online.

Every Wednesday at 12:30 p.m., as part of the Hammer’s Lunchtime Art Talks, a member of the museum’s curatorial department leads a short, free discussion about an individual work from the collection. Recently I joined a talk on Lorna Simpson’s “Backdrops Circa 1940s” (1990), led by curatorial assistant Vanessa Arizmendi. When I opened the Zoom link that had been emailed to me a few minutes prior to the event, I was surprised by the turnout — 180 attendees.

At the start, Arizmendi provided some tips and tricks for maximizing our Zoom experience, like using Speaker Mode and raising our hand in the Participants panel. Then she delivered an engaging presentation about Simpson, self-portraiture, and “Backdrops” itself. The work is stunning — a screenprint diptych on felt panels that places a photo of a young black woman lounging among the stars next to a photo of Lena Horne singing amid twinkling lights. As we look at one black woman posing in a photography studio and another performing on stage, we are made to examine our conceptions of glamour, and to ask ourselves whose images are worthy of reproduction.

¤

Some 70 miles east of the Hammer, the Inlandia Institute in Riverside has produced a particularly robust assortment of online programming. I’d never before heard of the nonprofit literary center, and I was deeply moved by their mission to support literary activity in the Inland Empire, where arts and culture have been historically underfunded. “Given how suddenly our lives changed with the pandemic and the safer-at-home orders,” says Executive Director Cati Porter, “we — as an organization whose main focus has been to provide free public events and workshops in venues across the region — had to act quickly in order to preserve some of what we had to offer.”

Many of Inlandia’s writing workshops were able to swiftly move to a virtual format, thanks to flexible workshop leaders who have utilized a variety of technologies like Facebook groups, Zoom, and Google Classroom. Inlandia decided to offer its fee-based workshops for free, “in acknowledgment of how the pandemic has affected many of our network’s members,” says Porter. The Institute has also been able to move many of its public events — including public readings and a live storytelling series called The Flame — online by broadcasting them on YouTube.

Inlandia Books, the Institute’s publishing arm, is also launching at least two new books virtually. One of them, San Bernardino, Singing, is an anthology of work by Inland writers edited by poet and educator Nikia Chaney. Through Inlandia’s Facebook events page, the Institute has serially released author readings, book giveaways, and special live author events. I’ve been particularly impressed with Inlandia’s social media savvy, as their Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter have been bustling ever since their physical location closed its doors.

Like the Bay Area Book Festival, Inlandia has hit rough spots along the way. “There are of course certain inherent challenges to holding virtual events, technology being a major one,” says Porter. “In addition to holding the events, we’ve also had to coach presenters on lighting, camera positioning, backgrounds, and engaging with the audience by looking and speaking directly into the camera — something that doesn’t come easily for many of us!” But the new configurations have also provided some unexpected benefits. “I can’t say that it’s been easy, but I’m happy that we’ve been able to quickly transition,” Porter says, “and in many cases our audience has grown because there are fewer competing events and we can reach outside of the confines of a commute.”

¤

The Women’s Center for Creative Work (WCCW), headquartered in Los Angeles’s Frogtown, has also swiftly moved many of its regular events and services online, now facilitating digital workshops and co-working sessions. Founded in 2013, the Center serves as a space for connecting L.A.’s feminist creative communities. I attended their digital discussion titled “Art in the Age of Emergency,” which was organized directly in response to our present moment. In front of nearly 70 attendees, moderator Yxta Maya Murray and panelists Alex Espinoza, Kathleen Kim, and Adee Roberson spoke about collective grief and mourning, what it means to be “essential,” the articulative power of art, the relationship between art and action, and the significance of race, class, ethnicity, and migration in conversations around COVID-19.

I was particularly struck by the smoothness of the Crowdcast presentation. Usually, remote events make me anxious — accidentally unmuted mics, videos freezing, a general uncertainty about who should talk when. But this time changes between different screens and speakers were seamless and aesthetically pleasing. It was also interesting to see these artists in their respective domestic spaces: Roberson, a visual artist, with paintings on her walls; Kim, a musician, with a piano behind her, melodica perched on top; and Espinoza, a writer, with bookshelves brimming.

Prior to the group discussion, each artist had a one-on-one conversation with Murray about how they’ve responded to COVID-19 in their practice and in their lives. Then each presented a work of art. Roberson first discussed her use of the quarantine as “generative time,” devoted not to making new work, but to research, reading, and relaxation. Now is a time for “processing and input,” she said, not necessarily productivity. Then she shared “we speak light,” an evocative three-minute video presentation. During the short film we see a pair of outstretched arms reaching for a crisp blue sky, waves crashing on a palm tree-spotted shoreline, sun streaming through green palm leaves, and figures in veiled baseball caps. It was both nostalgic and uncanny — while I longed for the summer sights that I know we won’t be able to enjoy this year, I also recognized that the facial coverings of the veiled figures were not unlike the ubiquitous face masks I see during my daily walks.

Next, Espinoza admitted that he has found it difficult to write during this time, “yet at the same time my work feels more urgent.” He’s felt especially challenged by the lockdown because “as writers, we need to participate with the world.” But he is determined to press on: “We’re passing through this period of trauma together,” he said. “That’s what art does — we have to look at the difficulty in order to shed light on it and understand what’s happening.” Then he read an excerpt from his novel-in-progress, which follows a group of strangers from different backgrounds dealing with various forms of loss — familial, personal, spiritual, and psychological. It’s about “collective grief,” Espinoza said in introducing the work, about “grief less as a private experience and more as a communal experience.”

Finally, Kim shared her feeling that the pandemic has “revealed our collective precarity,” and in fact exposes an entire “future of precarity.” Then she played an original composition that she said “contemplates the multiple meanings of the world ‘slur.’” A slur, Kim explained, has many definitions — a musical term, a euphemism for a racial insult, and a descriptor of speech. Throughout the song, Kim used the entirety of her violin, tapping on its body, plucking its strings, bowing, skidding. There was a fascinatingly “fractured aspect to the music,” Murray commented. Most interestingly, Kim used a looping pedal to play on top of her own bowing and also vocalize into a headset microphone. It sent chills up my forearms.

¤

Last night I had my museum dream again. I realize now it’s not really about museums — it’s about a yearning for shared spaces, communal experiences. It’s about wanting to go somewhere, to learn something, to see or hear the new and the nourishing. Even now, under quarantine, California’s most important cultural institutions are committed to feeding that need. I think more and more about something Alex Espinoza said during the talk at WCCW: in a moment like this, the role of art — and, more broadly, of culture — is to “try to make us feel connected while we are disconnected.” With a spirit of resilience and a sense of creativity, curators, workshop leaders, and artists of all stripes have done just that.

¤

Sophia Stewart is a writer, editor, and cultural critic from Los Angeles. You can find her writing here and follow her on Twitter @smswrites.

LARB Contributor

Sophia Stewart is a writer, editor, and cultural critic from Los Angeles. You can find her writing here and follow her on Twitter @smswrites.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Zoom and Gloom: Universities in the Age of COVID-19

Ryan Boyd considers two new books on higher education.

Pandemic Narratives and the Historian

Alex Langstaff interviews an international group of leading historians of public health, epidemics, and disaster science.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!