THE DISTANCE between the Hirshhorn Museum and the US Senate and House of Representatives is approximately one and a half miles. This summer, the hushed sanctum of the museum has been home to an exhibition of work by Iranian artist Shirin Neshat. It is possible to walk from the Senate to the Hirshhorn in less than half an hour, paying homage along the way to several monuments to wars and heroes of the still young American story. The Korean War Memorial is not far and the Washington Monument is right there. The narrative of Iran that Neshat tells in Facing History: Shirin Neshat is far more elusive, not owing to any inherent Iranian impenetrability, but because the American stance toward complexity and complicity tends to be one of tightly pursed lips, resolutely shut eyes, and hands clamped on ears. For nearly the past four decades, Iran has been the reliable bogeyman of the American political context; can the devilish attributes scrawled on its reality — the dehumanizing horns and talons, the genocidal intentions — be erased, or at least exposed for their artifice through art?

Neshat takes up this formidable question in work that humanizes her native land but also pushes questions about US complicity in its current fate. The Neshat exhibition is on display at a time when Iran’s future literally lies in the hands of American political officials. All summer, John Kerry, President Obama’s secretary of state, has been working to hammer out a nuclear deal that would permit a lifting of the sanctions that were placed on Iran following the Islamic Revolution of 1979. The two countries struck a deal on July 14, 2015, but House Republicans staunchly oppose it, denouncing the deal and its stipulations as an effective license for Iran to build nuclear weapons, and are threatening a veto. It was not until September 2, 2015, that the Obama Administration was able to gather enough votes in the US Senate to thwart Republican efforts to subvert the deal.

Neshat’s exhibition makes an artistic intervention into this complex political milieu — the transformation of a long held enemy into a potential friend. The assemblage of photographs and black-and-white video installations on view were made simultaneously with three periods of Iranian history. Together, they provoke a more complex conversation about Iran and the United States than has been possible in decades past. Contemporary political context intersects with the blank spaces of historical context that have typified the American encounter with Iran the enemy.

The work spans three periods in Iranian history. The first period begins with the 1953 ouster of Iran’s first democratically elected prime minister, Mohammad Mossadeq, orchestrated in large part by the United States. The second, far better known for its binary optics of extremism and tyranny, is the 1979 Islamic Revolution that led to the overthrow of the Shah and the ascent of Ayatollah Khomeini. The final period is the most recent, the hopeful if limitedly successful Green Revolution, which saw scores of Iranian youth, particularly women, taking to the streets of Tehran and demanding democracy and freedom from oppression. Together, the three constitute a denouement that challenges the singular story of Iran and Iranians as inexorable exemplars of oppression and tyranny, signaling that a deal with them would lead to tragedy. Speaking of President Obama in relation to the current arms deal, American presidential hopeful Mike Huckabee said, “He will take the Israelis and march them to the door of the oven.”

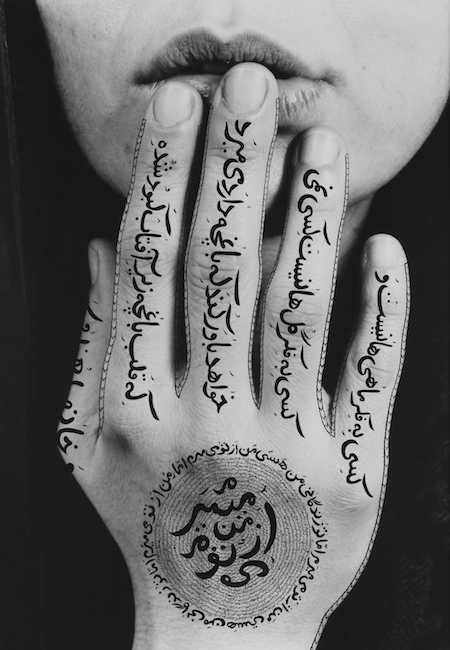

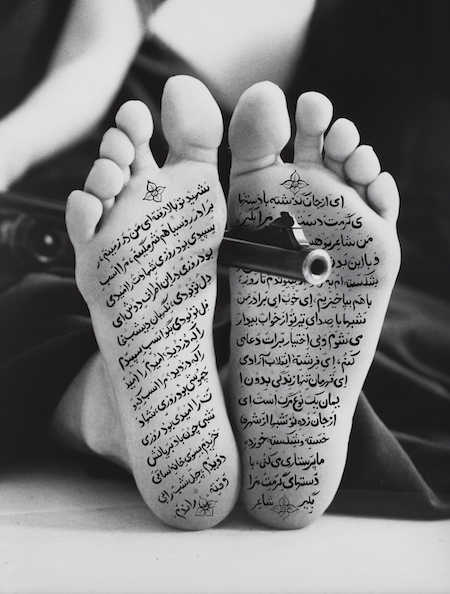

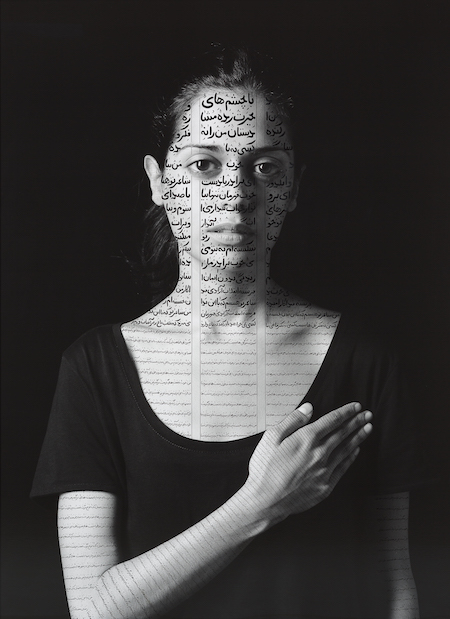

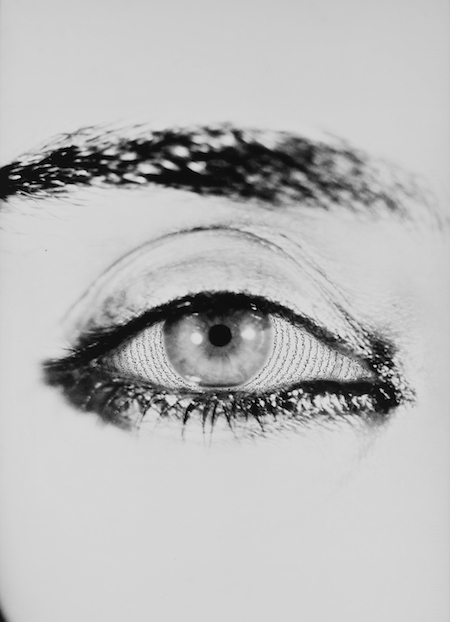

If the political takes the real and distorts it into caricatures that align with the political agendas of enemy-making, the artistic can do the opposite, unearth and enhance the real into the beautiful. In this exhibition, photographs from Neshat’s “Women of Allah” series are the strongest. In these portraits, the faces, eyes, and hands of the artist and other female subjects are transcribed with Persian poetry. This theme of transcription recurs in all three historical periods to which Neshat attends; here, the black-encased women of the past and fresh-faced male and female youth of the Green Revolution address the metaphorical Iran as it seems to appear to America and Americans — unintelligible and overwrought. The fact that this striated relationship can be and is, in Neshat’s delicate recreation, one of attraction and beauty is a testament that artistic possibility can achieve what the political may find impossible — or at least improbable.

The Muslim Feminist: Empowerment and Segregation

Just as the transcription of words and stories on Iranian faces bears a particular relationship with the Iranian-American political contemporary, so too does the presentation of veiled but armed women. At the time Neshat’s “Women of Allah” series was photographed (1993–1997), the post-revolution Iranian regime was one of the first to push the idea of Iranian women’s empowerment as a literal wielding of weapons. The image of women in black chadors clasping guns was a familiar part of the post-1979 Iranian Regime’s project of reconstituting the understanding of women’s empowerment not as a Western-derived pursuit of gender equality, but rather as a literal wielding of destructive power to fight for basic rights. In Neshat’s representation of ideas of segregation and militarization, guns and veils come together to represent the twin dangers a woman can pose, one of a palpable if veiled sexuality and the other of the literal bullet in the barrel.

In the years since Neshat created her iconic images of Iranian women, this competing idea of Muslim women’s agency and empowerment has spread beyond Iran. The darkly clad weapon-wielding woman of Neshat’s photograph Rebellious Silence994, features a chador-clad woman holding a gun barrel upright against her face such that it bisects her body in half. This woman warrior stares directly at the camera, her gaze both distant and resolute. In the decades since Rebellious Silence was shot, the idea of the covered woman as warrior has begun to signify a competing conception of empowerment centered on gender segregation rather than parity. Its visible anti-Western and anti-imperialist points of reference are imagined as more authentic for Iranian women than one focused only on equality, on women being like men, or other simplistic parallels tying unveiling with freedom. Because the Islamist veiled and armed woman warrior model is focused on complementarity instead of equality, it envisions the realms of men and women as separate but imbued with their own power structures in which women can rise to leadership. Some legitimacy for this conception of gender relations has been supplied by the doubts feminist scholars like Aysha Hidayatullah have expressed for the task of finding theological support for gender equality within Islamic theological texts. Power is hence being reconstructed and reconstituted: Neshat’s women wield guns and supplicate at the same time; their veils do not stanch their sexuality; the female gaze looking back at its audience is bold and unflinching. Women in orthodox religious schools in Iran and beyond — in Islamabad, in Muslim ghettoes in France and Britain — now consume and sometimes adopt this alternative conception of the feminine, a premonition of which appeared in Neshat’s “Women of Allah” series decades ago in images such as Rebellious Silence and Faceless (both works, 1994). (The latter also features a woman in chador, but now her gun is pointed at the viewer.)

This world of segregated spheres, where men and women live apart but remain connected, is distilled to its most elemental aspect in Neshat’s video installations. In the video Turbulent, 1998, two large screens are placed to the viewer’s right and left. On one, a man sings to an all male audience clad in white shirts; his words are legible and melodic even if their meaning is not intelligible to those who do not speak Persian. On the other, a woman sings a wordless melody to an empty hall; the man’s words were recognizable as words even to the non-Persian speaking viewer while the woman’s are guttural and haunting. Enveloping the listener, they represent rebellion and mourning, a destruction of silence and simultaneous refusal to use words that do not capture her pain, the words of men.

If Turbulence points to the artifice of gender segregation and perhaps to the consequent necessity of intelligibility between the spheres of male and female, the black-and-white photograph Untitled, 1997, points to its fictions. In the picture, a woman completely covered in a black chador, stands with a young boy whose naked body is adorned with henna-like patterns. Her single exposed arm clasps the boy’s hand. While theoretical constructs of gender segregation may pretend that separate spheres invalidate the need for submission of woman to man, the rules mandate that a lone woman cannot appear in public without a male guardian. The boy may be small, exposed, and seemingly powerless, but he is still more powerful than the woman who cannot exist publicly without him.

Exile and Iranian Artist

In Dante’s inferno, the poet’s coming exile is foretold with the following words: “You shall leave everything you most dearly loved: / This is the first one of the arrows which / The bow of exile is prepared to shoot.” In one of her public lectures, Neshat speaks poignantly of the weight of her banishment from that she loves most. The artist left Iran in 1974 and did not return until 10 years after the Islamic Revolution, only to find that the Iran she sought and hoped to find no longer existed. The stark contrasts and complications of the world that she did find became the impetus for her art. Her art, its critiques and questioning of the smug utopia that the Islamic Republic pretends to be, in turn have became the basis of her exclusion, her public critique of it in the West exposing her to revenge or reprisal from the regime if she chooses to return.

Torn from Iran, Neshat in her own words lives a nomadic life; her yearning for Iran — that what she loved most has been taken from her — has led to ceaseless searching for what seems most like Iran or represents some closeness in cast or context, in smell or scenery. Some of Neshat’s video installations and pictures are filmed in Morocco; a new project is set in Egypt. These Iran-like places, sometimes geographically proximate at other times culturally similar, are not and will never be Iran, and yet Iran remains the fulcrum around which all of Neshat’s artistic expression is centered. In fulfilling the artistic task of holding up a mirror to the society, Neshat has been banished from it. The irony of her artistic geography, however, does not end there; for in America, where her work is on view in the capital at one of the nation’s foremost museums, where its leaders discuss the future of Iran’s inclusion or exclusion and demonization or humanization, she is forever Iranian.

Art, the Enemy, and the Reclamation of History

On, May 15, 2015, the day on which Facing History: Shirin Neshat opened at the Hirshhorn Museum, The Washington Post’s critic Philip Kennicott complained in his review:

Unfortunately, the historical focus of the show doesn’t always serve Neshat’s work well. Historical photographs and even a newsreel give viewers a sense of these epochal events, but Neshat’s work isn’t particularly documentary in its focus. At its best, it is a kind of poetic descant to history, reimagining it in a lyrical and reflective mode. The exhibition’s approach also threatens to make Neshat into a conduit, or worse, a martyr, of the tragedies of Iranian history, inviting us to indulge the superficial and aggrandizing view of the artist as someone who suffers on behalf of her people.

Kennicott’s smug critique, and its discomfort with the ambiguities of Neshat’s work — its lack of ultimate prescription or resolution — reveals in sum the challenges of representing Iran, or really any Muslim country, within the American context. The dictates of the latter demand a particular narrative arc from the Muslim female artist, one in which the oppressions of faith and culture are duly and roundly denounced, the American elevation of them as the most corrosive and oppressive forces in existence consequently affirmed. In simple terms, American feminism beholds the Iranian or the Pakistani or the Syrian woman artist and recognizes only the feminism of rebellion, of throwing off, of repudiation. This myopia, which extends also to rules of inclusion and exclusion within the Western art world, has no time or energy and certainly no recognition for the feminisms of resilience, of women whose strengths are not simply encapsulated in the idea of rebellion.

In its overt rejection of this demand, Neshat’s work does the crucial task that feminisms of “other” places desperately need. Not all strength or all complexity is signified by the abandonment of one or another structure. More crucially, leaving out the contributions of feminisms of resilience, of the dead activist women of the Green Revolution who did not manage to overthrow but tried nevertheless, of the covered women, the supplicating women whose adorned hands represent inner worlds of lyricism and poetry, of a resilience that is not trite or showy, that provokes some discomfort in the Western viewer who expects one thing and gets another. It is this restriction of the feminist to that which confirms, either via the artist’s stance or the subject’s treatment, an exclusive elevation of the feminism of rebellion and a devaluation of suffering (martyrdom) that leaves out entire histories, denies Iranian women a legacy of their own.

Shirin Neshat: Facing History does not give American audiences yet another chance to pity Iran’s women in the manner to which they are so accustomed or to ignore their own government’s complicity in Iran’s contemporary political reality. What the exhibition accomplishes is far more complex: a feminist reclamation of history that tells Iran’s story via the female gaze, but refuses to distill it into easy binaries of terrible oppressive Islamic Iran and the lovely liberated and perfect United States. If the theistic authoritarianism of Iran’s regime doggedly insists that the segregated world it creates, where dissent is a crime and unfettered femininity a burden, then the United States is just as obstinate in its hunger for Iran to continue to play the enemy, its women eagerly awaiting prescriptions for liberation from their Western sisters, their struggles centered entirely on throwing off veils. The power of resilience, captured so evocatively in Neshat’s exhibition, forces the viewer to think beyond this simple recipe and ponder the interconnected fates of the male and female that makes simple oppositions only trite obfuscations. A feminist history of Iran, such as the one Neshat presents, threatens all of its audiences: the exclusionary Iranian regime, whose political project depends on affirming the moral perfection of a gender segregated society and the Americans who cannot bear to veer from the prescription of demonizing Iranian men so that they may pretend to rescue Iranian women.

¤

LARB Contributor

Rafia Zakaria is an attorney, a political philosopher and the author of The Upstairs Wife: An Intimate History of Pakistan (Beacon 2015). She is a columnist for Dawn Pakistan and Al Jazeera America.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Corita Kent: The Big G Stands for Goodness

Nun, activist, artist Corita Kent at the Pasadena Museum of California Art.

Kahlil Joseph’s Double Conscience: A Contemporary Spiritual

"Double Conscience," Kahlil Joseph's video project, is an elegant illustration of poverty, inner-city turmoil, and their multilayered impact on a...

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2015%2F09%2F03-Shirin_Neshat_Women_of_Allah_Allegiance_with_Wakefulness-small.jpg)