Sin, Glamour, and Photography in Hollywood’s Golden Age: On Two Books by Mark A. Vieira

By Chris YogerstMarch 14, 2020

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2020%2F03%2Fforbiddenhollywood.jpg)

Forbidden Hollywood by Mark A. Vieira

George Hurrell’s Hollywood by Mark A. Vieira

IF THERE ARE two qualities that define Hollywood’s Golden Age — especially the early 1930s — they are sin and glamour. From Cecil B. DeMille’s zeppelin orgy Madame Satan (1930) and Paul Muni’s blithely wielding a Tommy gun in Scarface (1932) to Mae West’s seductions in She Done Him Wrong (1933), such films define the era known to historians and a rising cadre of respectable bloggers as pre-Code, before the industry began censoring content in accordance with the Motion Picture Production Code in 1934. Some of the most symbolic images of the pre-Code era came from expert photographers hired by studios to capture sensational and scintillating stills of sex, violence, and general debauchery in glorious black-and-white. The most sought-after photographer was George Hurrell, father of the Hollywood glamour portrait, who started his career in the penultimate days of the spicy pre-Code years and continued into the 1990s.

Two books by Mark A. Vieira document the pre-Code era of Hollywood history through vivid pictures and astute storytelling. Forbidden Hollywood: The Pre-Code Era (1930–1934): When Sin Ruled the Movies details the years before the Production Code truly got its teeth. George Hurrell’s Hollywood: Glamour Portraits 1925–1992 chronicles one of the most desired photographers in American film history. As an author, photographer, and historian, Vieira combines his skills to highlight Hollywood history in a captivatingly visual way. Vieira’s curated photographs transport viewers back in time by capturing our attention through means unique to masterful photography.

The pre-Code films, Vieira writes, “shared a time, a place, and an attitude” from 1930 to 1934. Offering an escape from the Great Depression, filmmakers began to push the boundaries of industry strictures. The studios were also in financial straits due to the stock market crash, so Hollywood began producing increasingly edgy content as a means to keep audiences interested in spending their dwindling incomes on movies. Narratives ripped from the headlines of gangland newspapers and inspired by the affairs of speakeasy gals were projected across the country through celluloid on a weekly basis.

Some of the most talked about films from this period are sensual films featuring strong female leads. An early example Vieira cites is MGM’s The Trial of Mary Dugan (1929) starring Norma Shearer. The film, based on a hit Broadway play, deals with illicit relationships and features the actress in a negligee. This was enough to get the film banned in Chicago (ironic considering the state of corruption in the city at the time). Forbidden Hollywood sets up this vaunted period with a brief history of how the industry’s self-censorship came to be, followed by a series of relevant case studies with copious amounts of high-quality images. Vieira’s goal is to show us pre-Code Hollywood by “taking us there.” The vivid images in his book do just that.

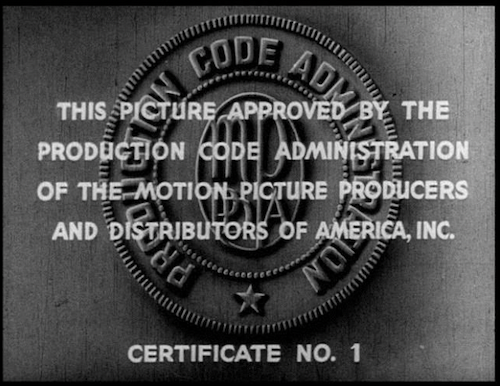

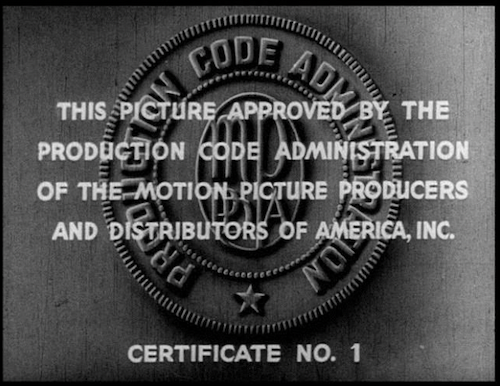

Though the Motion Picture Production Code was already in place beginning in 1922, the Code was largely unenforced in the 1920s. It was initially created by Will Hays, a Washington insider who was brought into the film industry to clean house and curb the tales of decadence coming out of Tinseltown. Fatty Arbuckle’s manslaughter charges, the death by poisoning of Olive Thomas, and the unsolved murder of director William Desmond Taylor led outsiders to believe that Hollywood was a hotbed of Babylonian happenings. Showing the government that the industry could police itself was a sign of good faith. The plan was to create a series of decency regulations that all films must either abide by or be denied exhibition. Officially, only films with a Code seal could be shown to the public, but seals were issued at will for many years.

In the late 1920s, state and local censorship boards were the primary hurdle for film distributors. Facing nearly 100 local boards nationwide, as well as eight state boards with regional influence, the pre-Code era faced more battles outside of Los Angeles than within it. These local and regional censors charged filmmakers for reviewing prints and added additional fees for edits made. The Virginia board, for example, reportedly charged over $27,000 in 1928 alone. As an industry, Hollywood shelled out up to $3.5 million a year to censor boards throughout the 1920s. One of the toughest censor boards was in Ohio — the state pushed back on Birth of a Nation (1915) for its racism, and that case solidified the lack of free speech protections for the film industry. Though they put up a formidable fight, local and regional censors generally did not prevent Hollywood from pushing social and cultural boundaries throughout the Roaring Twenties and into the next decade.

In 1931, just as James Cagney was about to shine in The Public Enemy, Will Hays shortsightedly announced that “the greatest of all censors — the American public — is beginning to vote thumbs down on the ‘hard-boiled’ realism in literature and on the stage which marked the post-war period.” He was wrong — The Public Enemy became a box office hit and helped solidify the gangster film as part of the standard pre-Code canon. Although the film was popular, special interest groups pushed back against such films because they depicted graphic violence and a laissez-faire attitude toward sex. Scarface (1932) faced similar protest, and producer Howard Hughes dumped a six-figure sum into battling the censors for two years straight. The film was ultimately released but would be regularly denied exhibition after 1934. In 1932, Jean Harlow drew censor animosity for her fast and loose attitude toward sexual relationships in Red-Headed Woman. Hollywood censor Lamar Trotti called the film “the most awful script I have ever read.” However, the film passed after a test audience reported feeling unsympathetic toward Harlow’s character.

Vieira details how 1934 changed everything for Hollywood. The Legion of Decency, a Catholic content censorship organization, was incorporated in April of that year. The following month, Legion of Decency insider and influential Catholic Joseph Breen helped administer a boycott of Warner Bros. cinemas in Philadelphia. With the powerful Catholic Church and its 20 million viewers threatening to boycott Hollywood altogether, the industry felt it had no choice but to give in. Intimidated, Will Hays told industry moguls, “the Catholic authorities can have anything they want.” A prominent archbishop promised Hays that the Church would back off if Hollywood simply enforced their own rules. By July, the Breen-led Production Code Administration became the juggernaut that would change movies for decades to come.

Not all films featured in Forbidden Hollywood were magnets for controversy, such as Universal’s Dracula and Frankenstein, but these films represent foundational works of the period (Vieira also discusses the much more controversial Island of Lost Souls). For some readers, Vieira’s pre-Code book will be an appropriate companion for histories such as Thomas Doherty’s Pre-Code Hollywood: Sex, Immorality, and Insurrection in American Cinema 1930–1934. The quality and significance of the images in Forbidden Hollywood are worth the price of admission alone.

Movie stars had long reached a perch of immortality by the late 1920s, and photographer George Hurrell felt their presentation in PR material and magazines was too ordinary for Hollywood icons. That perfect gloss that we associate with Hollywood’s golden years had much to do with Hurrell’s ability to capture stars’ beauty in a way few photographers could. Working out of the Granada Shoppes and Studios on Sunset Boulevard, Hurrell’s career took off shortly after he photographed actor Ramon Navarro. The actor was so impressed with his portraits that he showed them to MGM’s top star, Norma Shearer, while she was on the set of Their Own Desire (1929). Hurrell won over Shearer, as he was the first photographer who could capture her face in a way that corrected her eye misalignment. It was not long before Hurrell landed the job as head portrait photographer at MGM. Vieira’s book, George Hurrell’s Hollywood: Glamour Portraits 1925–1992, takes us on a journey through the artist’s work by way of large, glossy reprints of his most important photographs.

Paging through the book, you will notice it is part biography and part career exhibition. Some of the most famous stills of Hollywood celebrities originated through Hurrell’s lens. Along with his gifted eye, Hurrell had a way of relaxing his subjects as he sang along to the records playing the background. During that first shoot with Shearer, Hurrell told Vieira that he had nervously danced his way into a tripod. Quick to regain his composure, the photographer carried on dancing as he adjusted his camera.

One of Hurrell’s defining characteristics was his ability to get his subjects to emote sultriness through their facial expression. The pre-Code era saw many stars shedding clothes and bearing skin, but Hurrell did not need to rely on nudity for his subjects to appear sexy. A perfect example is the photo below of Paulette Goddard, identified with Hurrell’s signature in the bottom right corner.

Many artists have since tried to mimic Hurrell’s style, though none have been able to completely recreate the master. Particularly emblematic touches include Hurrell’s use of a single spotlight on a white backdrop, photographing subjects upside down, incorporating a Dutch tilt, featuring eyelash shadows, using a boom light to highlight hair and cheekbones, and avoiding the use of soft light. Hurrell preferred a wardrobe that created contrast. He also acknowledged the influence of his contemporaries, such as George Hoyningen-Huene and Cecil Beaton. Hurrell was loved by his subjects, especially the most self-conscious of them, because of his ability to carefully find photogenic angles.

While at MGM in the 1930s, Hurrell captured iconic images of Myrna Loy, Jean Harlow, Clark Gable, Joan Crawford, Lupe Vélez, Anna May Wong, and Carole Lombard. By the 1940s, Hurrell was at Warner Bros. snapping photos of Bette Davis, Humphrey Bogart, Ida Lupino, Olivia de Havilland, Lauren Bacall, and James Cagney. Other stars included Mae West, Buster Keaton, Gloria Swanson, Loretta Young, Rita Hayworth, Jane Russell, Katharine Hepburn, Paulette Goddard, and Veronica Lake. Hurrell also landed opportunities to photograph on film sets — Vieira’s book features several magnificent photographs shot during the making of Grand Hotel (1932).

An especially illuminating overleaf in the book features an untouched photo of Joan Crawford alongside its retouched counterpart. The untouched picture shows a (still beautiful) Crawford with a freckled face. The retouched photo shows the pristine, “impossibly beautiful” Crawford we know from the screen. The side-by-side images are striking in their difference, showing why Golden Age celebrities were worshiped as something larger than life. They did not represent reality, but a dream or delusion of perfection. While fascinating, it is sad to think about how such processes have created unnecessary pressure for today’s celebrities (and fans) to match unattainable beauty. That said, the untouched photo of Crawford demonstrates how one can exhibit beauty without the aid of editing.

When Hurrell began his work at Warner Bros., the toughest studio in town, he found one actress to be just as tough as the studio’s reputation. “I don’t want some glamour girl stuff,” sneered Bette Davis, “I want to be known as a serious actress and nothing else.” Davis did not initially like Hurrell’s glossy portraits. “I don’t want to look like a piece of shiny wax fruit,” she added. Hurrell took his time, danced to his music, and adjusted the wattage in his bulbs. Davis slowly came around. Upon looking at the first prints from Hurrell’s camera, the actress was delighted, “Hell, these are fine!”

Part of the reason Hurrell captured what other photographers simply could not is because he urged his subjects to lose the makeup. According to Hurrell, “In those days, it wasn’t easy, because the makeup was so caked, and they used such heavy makeup, too.” What he wanted to capture was the natural sheen that was lost when layers of makeup were applied. Some reluctantly agreed only because they knew the studios would be touching up the photographs anyway. However, for most, going in front of a camera without makeup showed great trust in Hurrell as an artist.

Vieira explains that the omnipresent word “icon” was not used to describe Hollywood celebrities until the 1970s. Film historian and critic John Kobal observed that the celebrities represented in images like Hurrell’s were “not real people.” During the Great Depression, “stars had to be removed from reality, from anything that had to do with mundane everyday life. It was as if the gods were stepping down from Mount Olympus to momentarily deal with mortal problems.” It is difficult to imagine a current celebrity that exudes the same iconographic presence that Clark Gable or Katharine Hepburn did generations ago. Vieira’s book pulls us into the world of the business of manufacturing icons, explores the process of creation, and lavishes in the joy of the final product.

Hurrell’s career ebbed and flowed over the years, and he worked steadily until his death in 1992. He photographed generations of stars, from Norma Shearer during the dawn of film sound to Natalie Wood, Bette Midler, Liza Minnelli, David Bowie, Lionel Richie, Chevy Chase, Barry Manilow, Aretha Franklin, Diana Ross, Harrison Ford, and Sharon Stone, among many others. Hurrell’s portraits are now the stuff of Hollywood legend. Vieira’s book provides an insightful narrative into both Hurrell’s life as well as the particulars of his artistic style that turned many into immortal icons.

Vieira’s books on the pre-Code era and Hurrell’s photography are well worth the read for both seasoned classic film fans and newcomers alike. The books are printed on quality stock that displays the true power of the star image. Whether it’s a film still, publicity shot, or studio portrait, static images are an essential ingredient for understanding Hollywood’s Golden Age. Images frozen in time allow us to ruminate on their power, appreciate their glamour, and understand why so many continue to be fascinated by stars of yesteryear.

Chris Yogerst is assistant professor of communication in the department of arts and humanities at the University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee. His next book, Hollywood Hates Hitler! Jew-Baiting, Anti-Nazism, and the Senate Investigation into War Mongering in Motion Pictures, will be published in September 2020 by the University Press of Mississippi.

Two books by Mark A. Vieira document the pre-Code era of Hollywood history through vivid pictures and astute storytelling. Forbidden Hollywood: The Pre-Code Era (1930–1934): When Sin Ruled the Movies details the years before the Production Code truly got its teeth. George Hurrell’s Hollywood: Glamour Portraits 1925–1992 chronicles one of the most desired photographers in American film history. As an author, photographer, and historian, Vieira combines his skills to highlight Hollywood history in a captivatingly visual way. Vieira’s curated photographs transport viewers back in time by capturing our attention through means unique to masterful photography.

¤

The pre-Code films, Vieira writes, “shared a time, a place, and an attitude” from 1930 to 1934. Offering an escape from the Great Depression, filmmakers began to push the boundaries of industry strictures. The studios were also in financial straits due to the stock market crash, so Hollywood began producing increasingly edgy content as a means to keep audiences interested in spending their dwindling incomes on movies. Narratives ripped from the headlines of gangland newspapers and inspired by the affairs of speakeasy gals were projected across the country through celluloid on a weekly basis.

Some of the most talked about films from this period are sensual films featuring strong female leads. An early example Vieira cites is MGM’s The Trial of Mary Dugan (1929) starring Norma Shearer. The film, based on a hit Broadway play, deals with illicit relationships and features the actress in a negligee. This was enough to get the film banned in Chicago (ironic considering the state of corruption in the city at the time). Forbidden Hollywood sets up this vaunted period with a brief history of how the industry’s self-censorship came to be, followed by a series of relevant case studies with copious amounts of high-quality images. Vieira’s goal is to show us pre-Code Hollywood by “taking us there.” The vivid images in his book do just that.

Though the Motion Picture Production Code was already in place beginning in 1922, the Code was largely unenforced in the 1920s. It was initially created by Will Hays, a Washington insider who was brought into the film industry to clean house and curb the tales of decadence coming out of Tinseltown. Fatty Arbuckle’s manslaughter charges, the death by poisoning of Olive Thomas, and the unsolved murder of director William Desmond Taylor led outsiders to believe that Hollywood was a hotbed of Babylonian happenings. Showing the government that the industry could police itself was a sign of good faith. The plan was to create a series of decency regulations that all films must either abide by or be denied exhibition. Officially, only films with a Code seal could be shown to the public, but seals were issued at will for many years.

In the late 1920s, state and local censorship boards were the primary hurdle for film distributors. Facing nearly 100 local boards nationwide, as well as eight state boards with regional influence, the pre-Code era faced more battles outside of Los Angeles than within it. These local and regional censors charged filmmakers for reviewing prints and added additional fees for edits made. The Virginia board, for example, reportedly charged over $27,000 in 1928 alone. As an industry, Hollywood shelled out up to $3.5 million a year to censor boards throughout the 1920s. One of the toughest censor boards was in Ohio — the state pushed back on Birth of a Nation (1915) for its racism, and that case solidified the lack of free speech protections for the film industry. Though they put up a formidable fight, local and regional censors generally did not prevent Hollywood from pushing social and cultural boundaries throughout the Roaring Twenties and into the next decade.

In 1931, just as James Cagney was about to shine in The Public Enemy, Will Hays shortsightedly announced that “the greatest of all censors — the American public — is beginning to vote thumbs down on the ‘hard-boiled’ realism in literature and on the stage which marked the post-war period.” He was wrong — The Public Enemy became a box office hit and helped solidify the gangster film as part of the standard pre-Code canon. Although the film was popular, special interest groups pushed back against such films because they depicted graphic violence and a laissez-faire attitude toward sex. Scarface (1932) faced similar protest, and producer Howard Hughes dumped a six-figure sum into battling the censors for two years straight. The film was ultimately released but would be regularly denied exhibition after 1934. In 1932, Jean Harlow drew censor animosity for her fast and loose attitude toward sexual relationships in Red-Headed Woman. Hollywood censor Lamar Trotti called the film “the most awful script I have ever read.” However, the film passed after a test audience reported feeling unsympathetic toward Harlow’s character.

Vieira details how 1934 changed everything for Hollywood. The Legion of Decency, a Catholic content censorship organization, was incorporated in April of that year. The following month, Legion of Decency insider and influential Catholic Joseph Breen helped administer a boycott of Warner Bros. cinemas in Philadelphia. With the powerful Catholic Church and its 20 million viewers threatening to boycott Hollywood altogether, the industry felt it had no choice but to give in. Intimidated, Will Hays told industry moguls, “the Catholic authorities can have anything they want.” A prominent archbishop promised Hays that the Church would back off if Hollywood simply enforced their own rules. By July, the Breen-led Production Code Administration became the juggernaut that would change movies for decades to come.

Not all films featured in Forbidden Hollywood were magnets for controversy, such as Universal’s Dracula and Frankenstein, but these films represent foundational works of the period (Vieira also discusses the much more controversial Island of Lost Souls). For some readers, Vieira’s pre-Code book will be an appropriate companion for histories such as Thomas Doherty’s Pre-Code Hollywood: Sex, Immorality, and Insurrection in American Cinema 1930–1934. The quality and significance of the images in Forbidden Hollywood are worth the price of admission alone.

¤

Movie stars had long reached a perch of immortality by the late 1920s, and photographer George Hurrell felt their presentation in PR material and magazines was too ordinary for Hollywood icons. That perfect gloss that we associate with Hollywood’s golden years had much to do with Hurrell’s ability to capture stars’ beauty in a way few photographers could. Working out of the Granada Shoppes and Studios on Sunset Boulevard, Hurrell’s career took off shortly after he photographed actor Ramon Navarro. The actor was so impressed with his portraits that he showed them to MGM’s top star, Norma Shearer, while she was on the set of Their Own Desire (1929). Hurrell won over Shearer, as he was the first photographer who could capture her face in a way that corrected her eye misalignment. It was not long before Hurrell landed the job as head portrait photographer at MGM. Vieira’s book, George Hurrell’s Hollywood: Glamour Portraits 1925–1992, takes us on a journey through the artist’s work by way of large, glossy reprints of his most important photographs.

Paging through the book, you will notice it is part biography and part career exhibition. Some of the most famous stills of Hollywood celebrities originated through Hurrell’s lens. Along with his gifted eye, Hurrell had a way of relaxing his subjects as he sang along to the records playing the background. During that first shoot with Shearer, Hurrell told Vieira that he had nervously danced his way into a tripod. Quick to regain his composure, the photographer carried on dancing as he adjusted his camera.

One of Hurrell’s defining characteristics was his ability to get his subjects to emote sultriness through their facial expression. The pre-Code era saw many stars shedding clothes and bearing skin, but Hurrell did not need to rely on nudity for his subjects to appear sexy. A perfect example is the photo below of Paulette Goddard, identified with Hurrell’s signature in the bottom right corner.

Many artists have since tried to mimic Hurrell’s style, though none have been able to completely recreate the master. Particularly emblematic touches include Hurrell’s use of a single spotlight on a white backdrop, photographing subjects upside down, incorporating a Dutch tilt, featuring eyelash shadows, using a boom light to highlight hair and cheekbones, and avoiding the use of soft light. Hurrell preferred a wardrobe that created contrast. He also acknowledged the influence of his contemporaries, such as George Hoyningen-Huene and Cecil Beaton. Hurrell was loved by his subjects, especially the most self-conscious of them, because of his ability to carefully find photogenic angles.

While at MGM in the 1930s, Hurrell captured iconic images of Myrna Loy, Jean Harlow, Clark Gable, Joan Crawford, Lupe Vélez, Anna May Wong, and Carole Lombard. By the 1940s, Hurrell was at Warner Bros. snapping photos of Bette Davis, Humphrey Bogart, Ida Lupino, Olivia de Havilland, Lauren Bacall, and James Cagney. Other stars included Mae West, Buster Keaton, Gloria Swanson, Loretta Young, Rita Hayworth, Jane Russell, Katharine Hepburn, Paulette Goddard, and Veronica Lake. Hurrell also landed opportunities to photograph on film sets — Vieira’s book features several magnificent photographs shot during the making of Grand Hotel (1932).

An especially illuminating overleaf in the book features an untouched photo of Joan Crawford alongside its retouched counterpart. The untouched picture shows a (still beautiful) Crawford with a freckled face. The retouched photo shows the pristine, “impossibly beautiful” Crawford we know from the screen. The side-by-side images are striking in their difference, showing why Golden Age celebrities were worshiped as something larger than life. They did not represent reality, but a dream or delusion of perfection. While fascinating, it is sad to think about how such processes have created unnecessary pressure for today’s celebrities (and fans) to match unattainable beauty. That said, the untouched photo of Crawford demonstrates how one can exhibit beauty without the aid of editing.

When Hurrell began his work at Warner Bros., the toughest studio in town, he found one actress to be just as tough as the studio’s reputation. “I don’t want some glamour girl stuff,” sneered Bette Davis, “I want to be known as a serious actress and nothing else.” Davis did not initially like Hurrell’s glossy portraits. “I don’t want to look like a piece of shiny wax fruit,” she added. Hurrell took his time, danced to his music, and adjusted the wattage in his bulbs. Davis slowly came around. Upon looking at the first prints from Hurrell’s camera, the actress was delighted, “Hell, these are fine!”

Part of the reason Hurrell captured what other photographers simply could not is because he urged his subjects to lose the makeup. According to Hurrell, “In those days, it wasn’t easy, because the makeup was so caked, and they used such heavy makeup, too.” What he wanted to capture was the natural sheen that was lost when layers of makeup were applied. Some reluctantly agreed only because they knew the studios would be touching up the photographs anyway. However, for most, going in front of a camera without makeup showed great trust in Hurrell as an artist.

Vieira explains that the omnipresent word “icon” was not used to describe Hollywood celebrities until the 1970s. Film historian and critic John Kobal observed that the celebrities represented in images like Hurrell’s were “not real people.” During the Great Depression, “stars had to be removed from reality, from anything that had to do with mundane everyday life. It was as if the gods were stepping down from Mount Olympus to momentarily deal with mortal problems.” It is difficult to imagine a current celebrity that exudes the same iconographic presence that Clark Gable or Katharine Hepburn did generations ago. Vieira’s book pulls us into the world of the business of manufacturing icons, explores the process of creation, and lavishes in the joy of the final product.

Hurrell’s career ebbed and flowed over the years, and he worked steadily until his death in 1992. He photographed generations of stars, from Norma Shearer during the dawn of film sound to Natalie Wood, Bette Midler, Liza Minnelli, David Bowie, Lionel Richie, Chevy Chase, Barry Manilow, Aretha Franklin, Diana Ross, Harrison Ford, and Sharon Stone, among many others. Hurrell’s portraits are now the stuff of Hollywood legend. Vieira’s book provides an insightful narrative into both Hurrell’s life as well as the particulars of his artistic style that turned many into immortal icons.

¤

Vieira’s books on the pre-Code era and Hurrell’s photography are well worth the read for both seasoned classic film fans and newcomers alike. The books are printed on quality stock that displays the true power of the star image. Whether it’s a film still, publicity shot, or studio portrait, static images are an essential ingredient for understanding Hollywood’s Golden Age. Images frozen in time allow us to ruminate on their power, appreciate their glamour, and understand why so many continue to be fascinated by stars of yesteryear.

¤

Chris Yogerst is assistant professor of communication in the department of arts and humanities at the University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee. His next book, Hollywood Hates Hitler! Jew-Baiting, Anti-Nazism, and the Senate Investigation into War Mongering in Motion Pictures, will be published in September 2020 by the University Press of Mississippi.

LARB Contributor

Chris Yogerst, a regular contributor to the Los Angeles Review of Books, is an associate professor of communication at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee. His most recent book is The Warner Brothers (2023). Chris is also the author of From the Headlines to Hollywood: The Birth and Boom of Warner Bros. (2016) and Hollywood Hates Hitler! Jew-Baiting, Anti-Nazism, and the Senate Investigation into Warmongering in Motion Pictures (2020). His writing can be found in The Hollywood Reporter, The Washington Post, The Journal of American Culture, and Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television. Find him on Twitter @chrisyogerst as well as Instagram and Facebook @cyogerst.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Road to Glory: Faulkner’s Hollywood Years, 1932–1936

Lisa C. Hickman reconstructs William Faulkner’s tumultuous Hollywood sojourn of 1932–1936.

Into the Archives: On “Letters from Hollywood”

Chris Yogerst reviews a revealing collection of letters from the Golden Age of Hollywood.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!