LARB PRESENTS the March installment of “Real Life Rock Top 10,” a monthly column by cultural critic Greil Marcus.

The Gang of Four were a four-piece band of critical thinkers: Dave Allen, bassist; Hugo Burnham, drummer and one-time-only vocalist; Andy Gill, guitarist and singer; Jon King, singer and melodica player. Except for Allen, who joined via an ad looking for a FAST RIVVUM AND BLUES BASSIST, they came out of the University of Leeds art department and film program in 1977. Though the band formally dissolved in 1984, with Allen and Burnham already gone, Gill and King, with two new, much younger members, were performing with undimmed fervor as the Gang of Four in 2011; after that, until his death last year, Gill used the name.

Nothing any of them did or didn’t do since their first recording in 1978 has lessened the shock of their sound. Their aesthetic was argument — people arguing with each other, with themselves, with history, with the news, with the world at large. Their means of getting any and all of that across were chopped-up rhythms and broken-up song lyrics. As Steve Albini puts it in the box set Gang of Four 77–81 (Matador), “Many of their songs were arranged so they could be played indefinitely, or as long as it took to get the point across.”

The 77–81 vinyl box is the first such anniversary/commemoration/milestone production — because of the United States Copyright Act of 1976, which allows recording artists to reclaim rights to recordings after 35 years, this is a US-only release — I’ve actually taken pleasure in, as something to hold, open, look at, read, play, listen to. I don’t think that’s because I first met the band in 1980, or because I contributed a paragraph to the book that’s part of the set: when I came across it I realized I’d forgotten all about it. It’s because if the music collected here were appearing for the first time, today, it would sound as much as if it were wiping the table clean as it did before, just as the objects in the box carry the glow left by people who actually did something, something that that world at large can look back on and say, Well — what was that?

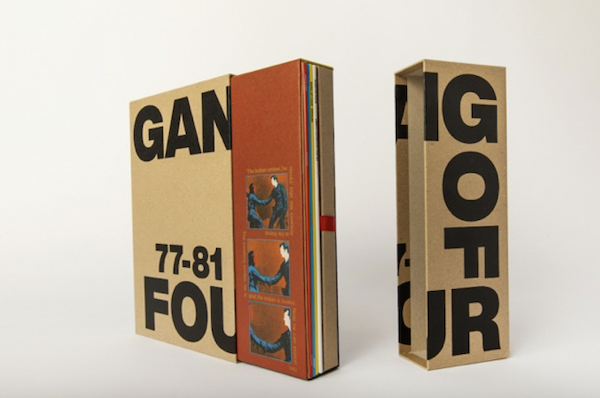

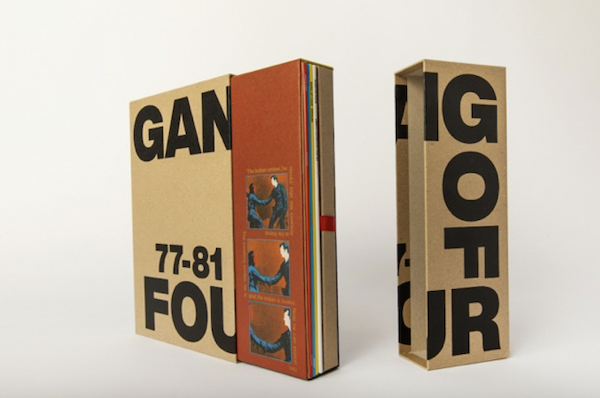

What it is, now, is a (1) big, reinforced box, with De Stijl borders around a New Sobriety design cut into the pidgin-critical-thinking part of the original Entertainment! front sleeve — a tripled movie-still image of a cowboy shaking hands with an Indian with captions running down their sides (“The Indian smiles, he thinks the cowboy is his friend”; “The cowboy smiles, he is glad the Indian is fooled”; “Now he can exploit him”). Running in block letters around the box itself is a line — a motto? a manifesto? — from the Entertainment! track “Natural’s Not in It”: “THIS HEAVEN GIVES ME MIGRANE.” Designed by King and Bjarke Vind Normann, it’s such a thing in itself, its own statement, that even if it were empty it would carry a charge.

Inside the box are LP versions of (2) Entertainment! (first released in the United Kingdom, on EMI, in 1979, in the United States, on Warner Bros., in 1980), and (3) the band’s second album, Solid Gold, from 1981; (4) an album of singles, most crucially “It’s Her Factory,” Burnham’s stand-up critique of a news item about housework, with Gill on drums, with live performances of “Cheeseburger” and “What We All Want,” as they appeared on Solid Gold in the same studio versions released as 45s; (5 & 6) Gang of Four Live at the American Indian Center 1980 SFO, a tremendous show as a double LP, with at the end the band all but outplaying the songs, or themselves, for “At Home He’s a Tourist” and “Return the Gift,” both of them inflamed accounts of people trapped in the capitalist hegemonies that produce false identities and free samples; (7) two “Gang of Four 77–81” buttons — every box set has to have at least a little piece of junk to demean you for what you paid for it; (8) a cassette with demos from 1977 on, starting with the otherwise unheard “The Things You Do” from a build-the-band rehearsal to stripped-down Solid Gold songs where the perspective the band started with — utter horror at the discovery that the THE WORLD IS REALLY LIKE THIS — is replaced by a less fractured attempt to see the world as a totality, every humiliation or satisfaction part of the means of exchange; (9) King and Burnham’s assembled chronicle, in book form, of what happened, how and why, with testaments from musical comrades, many replicant photographs, and song lyrics; and (10) in a pocket in the book, a sheaf of rejection letters from record companies, now reading hilariously for the stupidity of their language, from the tangled bureaucratese of A&M (“it has been decided that we will not be interested in a more extensive investigation of your work at this time”) to the ungodly hip of Stiff (“if there is no tape with this letter, then we’ve either lost it, or are considering taking it further and putting it out as a hit under another name”).

The Gang of Four offered a drama of false consciousness produced by consumerism, and a dramatization of the state of mind that came with it: the inability to think straight. This isn’t a matter of words, whether sung in a hysterical rush by King in “I Found That Essence Rare,” “Return the Gift,” “What We All Want,” or “Natural’s Not in It” (“The problem of leisure / What to do for pleasure / Coercion of the senses, we are not so gullible / Our great expectations, a future for the good / Fornication makes you happy, no escape from society”) or quietly analyzed by Gill in “Anthrax,” “Paralysed,” or “Why Theory” (following up the most unlikely song title in pop history with a staccato lecture that’s also like the kind of bar talk that happens when the drunk next to you has reached the state where everything is absolutely almost clear [“We’ve all got opinions / Where do they come from? / Each day seems like a natural fact”]). In Gang of Four songs, lyrics are a kind of guide vocal to the intellectual argument being made sonically, as one or two instruments are dropped out of a song as if at random, and then crash back in, as rhythms are scattered and reassembled with pieces missing so that as the progression of a song continues you hear the song questioning itself. That’s what happens in “Return the Gift,” as the song seems to be asking you to listen to each instrument, voice, guitar, drums, bass, individually, all the way through, so you have to play the song four times to hear it once. That’s what happens in “At Home He’s a Tourist,” as radical a piece of music that has been heard since, oh, maybe World War II. Gill is setting off bombs when he should be constructing a pattern, buttressing the argument King is making about the dislocation that occurs when you look in the mirror, or the mirror of other people’s faces, and realize you have no idea whom you or they are seeing. Instead Gill seems to be attacking the very idea that there could or should be an argument about anything so absurd, cruel, mean, disgusting, and real, which is to say the life that the guitarist like the singer or the drummer or the bassist or whoever might be listening goes through every day, when obviously the only proper response is to bang your head against the wall until everything in it comes out.

For me, this came together most surprisingly in two new places. First it was in the band’s first recorded step here, “The Things You Do” demo — excitement pushed by a kind of literary authority, not people fooling around with an art form that isn’t really theirs (“They were writing about rich schoolboy subjects and politics in London,” said Jimmy Douglass, the American record man who produced Solid Gold) but taking authority from one form, transferring it to another, and finding that the shift is producing something they could never have expected but recognize as if it’s what they’ve been looking for all their lives. And then it was in the way song lyrics read in the book, which wasn’t just a matter of finding out that what I always thought was “I do love a new purchase” in “Natural’s Not in It” is actually “Ideal love a new purchase.” (“I thought for years it was, ‘I do love a new purchase,’ as well,” Burnham said when I mentioned it. “Please don’t tell Jon I said that. Or I may have to kiss this guy.”) That’s because, in stark black lettering, they are almost objects before they’re anything else. They read like the internal captions in John Heartfield posters: mini cut-up essays about reification and what to do about it (be shocked, hire a private detective, have a drink, have two more, go to sleep, wake up and break an appliance). As you read, you’re brought into the energy and paradox of multiple voices: maybe different voices of different people, maybe different voices within the same person.

Loud, or whispered. Mumbled doubts against someone who sounds as if he’s willing to risk his life if that’s what it takes to make you believe he doesn’t know what he’s talking about but might if he can make it to the next verse. With King dancing like a puppet with half its strings cut, being jerked across the stage by some invisible agency while Gill stepped forward, holding himself still as if the only way to face up to the catastrophe is not to blink, the Gang of Four were frightening and thrilling; more frightening song by song, most thrilling when it was over and you walked out wondering what had happened. Curtis Crowe of Pylon, writing about a show where they opened for the Gang of Four in 1979, captures it. “When the first chord struck,” he says, “the entire room took one step back.”

Gang of Four 77–81 as an LP box carries a list price of $174.99. It is available as a CD set, with the book, without the buttons, and with a download coupon for the LP box cassette, for $79.99. Charles Taylor writes: “I got the LP box. I get so much pleasure from the physical fact of vinyl as opposed to CDs. I pore over the covers instead of just stacking them. And, I can’t explain this, I pay better attention.” The set does not include the Gang of Four’s first release, the 1978 “Damaged Goods,” “Love Like Anthrax,” and “Armalite Rifle,” on the Edinburgh label Fast Product, because there is no equivalent to the “35-Year Law” in the United Kingdom.

Thanks to Michelangelo Matos and Andrew Hamlin.

Greil Marcus contributed an introduction to the new Strange Attractor edition of Cathi Unsworth’s 2009 Sixties London mystery Bad Penny Blues.

¤

The Gang of Four were a four-piece band of critical thinkers: Dave Allen, bassist; Hugo Burnham, drummer and one-time-only vocalist; Andy Gill, guitarist and singer; Jon King, singer and melodica player. Except for Allen, who joined via an ad looking for a FAST RIVVUM AND BLUES BASSIST, they came out of the University of Leeds art department and film program in 1977. Though the band formally dissolved in 1984, with Allen and Burnham already gone, Gill and King, with two new, much younger members, were performing with undimmed fervor as the Gang of Four in 2011; after that, until his death last year, Gill used the name.

Nothing any of them did or didn’t do since their first recording in 1978 has lessened the shock of their sound. Their aesthetic was argument — people arguing with each other, with themselves, with history, with the news, with the world at large. Their means of getting any and all of that across were chopped-up rhythms and broken-up song lyrics. As Steve Albini puts it in the box set Gang of Four 77–81 (Matador), “Many of their songs were arranged so they could be played indefinitely, or as long as it took to get the point across.”

The 77–81 vinyl box is the first such anniversary/commemoration/milestone production — because of the United States Copyright Act of 1976, which allows recording artists to reclaim rights to recordings after 35 years, this is a US-only release — I’ve actually taken pleasure in, as something to hold, open, look at, read, play, listen to. I don’t think that’s because I first met the band in 1980, or because I contributed a paragraph to the book that’s part of the set: when I came across it I realized I’d forgotten all about it. It’s because if the music collected here were appearing for the first time, today, it would sound as much as if it were wiping the table clean as it did before, just as the objects in the box carry the glow left by people who actually did something, something that that world at large can look back on and say, Well — what was that?

What it is, now, is a (1) big, reinforced box, with De Stijl borders around a New Sobriety design cut into the pidgin-critical-thinking part of the original Entertainment! front sleeve — a tripled movie-still image of a cowboy shaking hands with an Indian with captions running down their sides (“The Indian smiles, he thinks the cowboy is his friend”; “The cowboy smiles, he is glad the Indian is fooled”; “Now he can exploit him”). Running in block letters around the box itself is a line — a motto? a manifesto? — from the Entertainment! track “Natural’s Not in It”: “THIS HEAVEN GIVES ME MIGRANE.” Designed by King and Bjarke Vind Normann, it’s such a thing in itself, its own statement, that even if it were empty it would carry a charge.

Inside the box are LP versions of (2) Entertainment! (first released in the United Kingdom, on EMI, in 1979, in the United States, on Warner Bros., in 1980), and (3) the band’s second album, Solid Gold, from 1981; (4) an album of singles, most crucially “It’s Her Factory,” Burnham’s stand-up critique of a news item about housework, with Gill on drums, with live performances of “Cheeseburger” and “What We All Want,” as they appeared on Solid Gold in the same studio versions released as 45s; (5 & 6) Gang of Four Live at the American Indian Center 1980 SFO, a tremendous show as a double LP, with at the end the band all but outplaying the songs, or themselves, for “At Home He’s a Tourist” and “Return the Gift,” both of them inflamed accounts of people trapped in the capitalist hegemonies that produce false identities and free samples; (7) two “Gang of Four 77–81” buttons — every box set has to have at least a little piece of junk to demean you for what you paid for it; (8) a cassette with demos from 1977 on, starting with the otherwise unheard “The Things You Do” from a build-the-band rehearsal to stripped-down Solid Gold songs where the perspective the band started with — utter horror at the discovery that the THE WORLD IS REALLY LIKE THIS — is replaced by a less fractured attempt to see the world as a totality, every humiliation or satisfaction part of the means of exchange; (9) King and Burnham’s assembled chronicle, in book form, of what happened, how and why, with testaments from musical comrades, many replicant photographs, and song lyrics; and (10) in a pocket in the book, a sheaf of rejection letters from record companies, now reading hilariously for the stupidity of their language, from the tangled bureaucratese of A&M (“it has been decided that we will not be interested in a more extensive investigation of your work at this time”) to the ungodly hip of Stiff (“if there is no tape with this letter, then we’ve either lost it, or are considering taking it further and putting it out as a hit under another name”).

The Gang of Four offered a drama of false consciousness produced by consumerism, and a dramatization of the state of mind that came with it: the inability to think straight. This isn’t a matter of words, whether sung in a hysterical rush by King in “I Found That Essence Rare,” “Return the Gift,” “What We All Want,” or “Natural’s Not in It” (“The problem of leisure / What to do for pleasure / Coercion of the senses, we are not so gullible / Our great expectations, a future for the good / Fornication makes you happy, no escape from society”) or quietly analyzed by Gill in “Anthrax,” “Paralysed,” or “Why Theory” (following up the most unlikely song title in pop history with a staccato lecture that’s also like the kind of bar talk that happens when the drunk next to you has reached the state where everything is absolutely almost clear [“We’ve all got opinions / Where do they come from? / Each day seems like a natural fact”]). In Gang of Four songs, lyrics are a kind of guide vocal to the intellectual argument being made sonically, as one or two instruments are dropped out of a song as if at random, and then crash back in, as rhythms are scattered and reassembled with pieces missing so that as the progression of a song continues you hear the song questioning itself. That’s what happens in “Return the Gift,” as the song seems to be asking you to listen to each instrument, voice, guitar, drums, bass, individually, all the way through, so you have to play the song four times to hear it once. That’s what happens in “At Home He’s a Tourist,” as radical a piece of music that has been heard since, oh, maybe World War II. Gill is setting off bombs when he should be constructing a pattern, buttressing the argument King is making about the dislocation that occurs when you look in the mirror, or the mirror of other people’s faces, and realize you have no idea whom you or they are seeing. Instead Gill seems to be attacking the very idea that there could or should be an argument about anything so absurd, cruel, mean, disgusting, and real, which is to say the life that the guitarist like the singer or the drummer or the bassist or whoever might be listening goes through every day, when obviously the only proper response is to bang your head against the wall until everything in it comes out.

For me, this came together most surprisingly in two new places. First it was in the band’s first recorded step here, “The Things You Do” demo — excitement pushed by a kind of literary authority, not people fooling around with an art form that isn’t really theirs (“They were writing about rich schoolboy subjects and politics in London,” said Jimmy Douglass, the American record man who produced Solid Gold) but taking authority from one form, transferring it to another, and finding that the shift is producing something they could never have expected but recognize as if it’s what they’ve been looking for all their lives. And then it was in the way song lyrics read in the book, which wasn’t just a matter of finding out that what I always thought was “I do love a new purchase” in “Natural’s Not in It” is actually “Ideal love a new purchase.” (“I thought for years it was, ‘I do love a new purchase,’ as well,” Burnham said when I mentioned it. “Please don’t tell Jon I said that. Or I may have to kiss this guy.”) That’s because, in stark black lettering, they are almost objects before they’re anything else. They read like the internal captions in John Heartfield posters: mini cut-up essays about reification and what to do about it (be shocked, hire a private detective, have a drink, have two more, go to sleep, wake up and break an appliance). As you read, you’re brought into the energy and paradox of multiple voices: maybe different voices of different people, maybe different voices within the same person.

Loud, or whispered. Mumbled doubts against someone who sounds as if he’s willing to risk his life if that’s what it takes to make you believe he doesn’t know what he’s talking about but might if he can make it to the next verse. With King dancing like a puppet with half its strings cut, being jerked across the stage by some invisible agency while Gill stepped forward, holding himself still as if the only way to face up to the catastrophe is not to blink, the Gang of Four were frightening and thrilling; more frightening song by song, most thrilling when it was over and you walked out wondering what had happened. Curtis Crowe of Pylon, writing about a show where they opened for the Gang of Four in 1979, captures it. “When the first chord struck,” he says, “the entire room took one step back.”

¤

Gang of Four 77–81 as an LP box carries a list price of $174.99. It is available as a CD set, with the book, without the buttons, and with a download coupon for the LP box cassette, for $79.99. Charles Taylor writes: “I got the LP box. I get so much pleasure from the physical fact of vinyl as opposed to CDs. I pore over the covers instead of just stacking them. And, I can’t explain this, I pay better attention.” The set does not include the Gang of Four’s first release, the 1978 “Damaged Goods,” “Love Like Anthrax,” and “Armalite Rifle,” on the Edinburgh label Fast Product, because there is no equivalent to the “35-Year Law” in the United Kingdom.

¤

Thanks to Michelangelo Matos and Andrew Hamlin.

¤

Greil Marcus contributed an introduction to the new Strange Attractor edition of Cathi Unsworth’s 2009 Sixties London mystery Bad Penny Blues.

LARB Contributor

Greil Marcus is a critic who lives in Oakland. This year, Yale will publish More Real Life Rock: The Wilderness Years, 2014-2021 (May) and Folk Music: A Bob Dylan Biography in Seven Songs (Fall).

LARB Staff Recommendations

Real Life Rock Top 10: February 2021

LARB presents the February 2021 installment of “Real Life Rock Top 10,” a monthly column by cultural critic Greil Marcus.

Real Life Rock Top 10: January 2021

LARB presents the January installment of “Real Life Rock Top 10,” a monthly column by cultural critic Greil Marcus.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2021%2F03%2FMarcusColumnmarch2021.png)