LARB IS THE NEW HOME for “Real Life Rock Top 10,” a monthly column by cultural critic Greil Marcus.

1. + 2. Bettye LaVette, “Strange Fruit” (Verve) and H.R. 35 Emmett Till Antilynching Act, carried by Representative Bobby Rush (D-Illinois). Abel Meeropol wrote “Strange Fruit” in 1937, as part of the campaign to make lynching a federal crime: to pass a law that had been blocked in Congress since 1918. Billie Holiday recorded it two years later and made it part of American history.

Bettye LaVette sings the song as if she’d just heard it, out of the blue, and couldn’t not but put her voice to it, as if no one ever had. There’s shock hiding in the burr of her voice, as if she’s seeing what she’s singing about for the first time, as if the bulging eyes and the twisted mouth were never quite as real for her as they are now.

This year the House passed Bobby Rush’s anti-lynching bill 410-4; with the backing of 99 members, it was set to pass the Senate in June when Rand Paul put a hold on it (he wanted to make it “stronger,” he said, but that was complicated, and — ). The bill remains in limbo. There’s so much more to focus on: the virus, the next relief bill, federal agents in disguise disappearing people into unmarked cars, but Rush has a record of persistence. He was a founder of the Chicago chapter of the Black Panthers; in 1992, decades after the murder of Panther chairman Fred Hampton by the Chicago police, he was elected to Congress. I will never forget the little item in the paper about his being challenged in the 2000 Democratic primary by a former editor of the Harvard Law Review. “What a carpetbagger,” I remember thinking. Rush defeated Barack Obama by two to one.

3. Mekons, Exquisite. A socially distanced album, or in Mekon Jon Langford’s words “long distance file sharing: Sally and I in Chicago but did not meet up during the process. Tom was looking after his Dad for much of it down in Sussex with only a cell phone. Rico in Aptos CA. Steve played drums in a basement in Brooklyn into a cell phone. Susie and Lu on either side of the Thames — not meeting up as Susie and her husband both had full on COVID. The saving grace was Dave Trumfio our bass player isolating in Silver Lake with a full recording studio so he was the final stop for all the files. I decided to see what I could do with my phone to encourage the others even though I have a home studio in the basement.”

What they came up with is stirring and incomplete. “Nobody,” with Tom Greenhalgh leading, calls back the despairing isolation of “King Arthur” in 1986 — there it was political, here it’s a social, physical fact that won’t hold still. The song is like its own lost chord, drifting too far from the shore: it’s scary. But “What Happened to Delilah” is the other side of the story: quick, a leap, another leap, a punk ring shout, first made of affection between friends, then a sign of community.

4. Peggy Noonan, “The Week It Went South for Trump,” The Wall Street Journal (June 25). “The real picture at the Tulsa rally was not the empty seats so much as the empty faces — the bored looks, the yawning and phone checking, as if everyone was re-enacting something, hearing some old song and trying to remember how it felt a few years ago, when you heard it the first time.”

5. Eric Church, “Stick That in Your Country Song” (UMG Nashville). Can you be cool and inflamed at the same time? This is Church’s “Born in the U.S.A.” written in 2015, recorded in January, released at the end of June. There’s no reference to a pandemic or a man being slowly tortured and killed in public on an American street, not literally, but you can’t not see all or any of that as the song plays. This is the country turning its back on every promise it ever made, until rage rolls over every concise, pungent, necessary argument: “Rock me hard, stop my heart / And blow the speakers right out of this car.” The song gets louder as it goes on, but the real volume is there in the start, the very first time Church spits out the title phrase, so coolly, so inflamed, that he puts a silent word on it: “Stick that in your country song, motherfuckers.”

6. + 7. Lady A, “Dear Fans” (Instagram, and comment June 11). As many have, you can call Lady Antebellum’s announcement that they’d changed their name to Lady A to rid it of the stain of slavery trivial, and you can say they put the name right back when they sued a Black blues singer who performs under the same name. But the Instagram comments following the announcement show it was anything but trivial, this being only one of the more articulate responses (the most articulate was “Bravo!”): “Unbelievable! who exactly are you pandering to? EVERY LIFE MATTERS!! Go ahead Keep the race narrative alive. Sorry I was a fan. Not anymore. Ask the DIXIE CHICKS HOW PANDERING WENT FOR THEM. Good luck.”

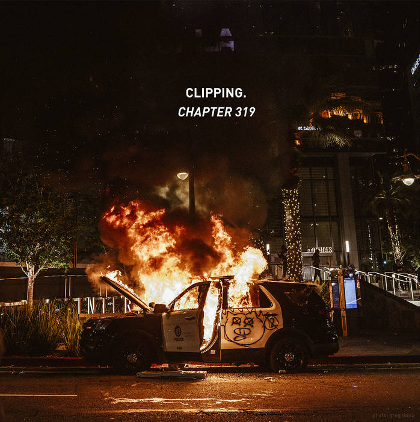

8. clipping, “Chapter 319.” The art for this precise, short, withering stomp by the techno-hip-hop-Afro-futurist-whatever-they-will-not-call-themseves-next trio — Daveed Diggs, voice, William Hutson and Jonathan Snipes, machines — beautiful as it is (and I don’t mean righteous-beautiful, I mean its sleeve art: it’s a perfectly composed image that you can’t help but respond to aesthetically, consciously or not) only grounds the music, it doesn’t speak for it.

clipping is the perfect name for this group: Diggs seems to clip a split-split second off every line-closing consonant, while Hutson and Snipes seem to trim their beats from the front, kicking them forward into the music a split-split second before you’re expecting to hear them. Diggs can rush past his lines — “Fuck the history lesson you know you know by now,” says the man who played Jefferson and Lafayette in the original cast of Hamilton (“The fact that we were all here playing the founding fathers and mothers of this country implies a sort of ownership over our country’s history that I had never felt before,” he’s said). He can bring the song to a halt, a cop flashing his lights and shining his flashlight in its face: “Donald Trump is a white supremacist — full stop. If you vote for him again you’re a white supremacist — full stop.” The record shows up, says its piece, and leaves.

9. Hightown opening credits, produced by Jerry Bruckheimer (Starz). They use “Vacation” by the Textones (the unglossy, unprofessional 1980 recording of the song Kathy Valentine brought to the Go-Go’s) over the opening montage, a portrait of Provincetown, the end of Cape Cod as the end of the earth. You see a utopia of gay bars, fishing boats, transvestites dancing in the street, a multi-sex Poseidon leading a parade and unfolding his arms as if he’s inviting you into the future. It’s irresistible, so sensuous you can’t take your eyes off of it, so fast in its humor — a bag of shrimp is dumped in one quick cut, a bag of syringes in the next — that the very good crime show that follows never quite catches up to it. But the first season only just ended.

10. Ted Widmer, Lincoln on the Verge: Thirteen Days to Washington (Simon & Schuster). American presidential historian, Bill Clinton speechwriter, and Lord Rockingham in the 1990s band Upper Crust, Widmer throws you into a cauldron of jeopardy and suspense and never lets go. Abraham Lincoln is leaving Springfield, Illinois, by train, with Indianapolis his first of the 16 stops it will take him to reach Washington, DC, for his inauguration — if he makes it, if the capital is still there. At the same time, Jefferson Davis is on his own train from Mississippi to Montgomery, Alabama, to assume the presidency of the Confederacy, and if Maryland goes, the government will have to flee. An assassination plot in Baltimore has been uncovered, but not contained, and in fact Lincoln is facing assassination every time he gives a speech, not that the speeches are hobbled and stiff. In Indianapolis, where everything — whether Indiana too might secede — is riding on it, he compares secession to one of the free-love cults that had been outraging Christian society throughout the century. “The refusal to fall apart in 1861 made a difference,” Widmer ends quietly, echoing Melville’s daunting “The Declaration of Independence makes a difference,” just a line in a letter to his editor in 1849. Finally the book is an act of fraternity, subject and writer as democratic brethren — not that Widmer would make such a claim for himself. “It’s definitely about Lincoln,” he says of the 13 days 159 years ago, “but some small piece of this story came from the experience of being in a band, traveling around the country between low-paying gigs.”

Thanks to J.-M. Büttner and Steve Weinstein.

A new and illustrated edition of Greil Marcus’s 1975 book Mystery Train has been issued by the Folio Society in London.

¤

1. + 2. Bettye LaVette, “Strange Fruit” (Verve) and H.R. 35 Emmett Till Antilynching Act, carried by Representative Bobby Rush (D-Illinois). Abel Meeropol wrote “Strange Fruit” in 1937, as part of the campaign to make lynching a federal crime: to pass a law that had been blocked in Congress since 1918. Billie Holiday recorded it two years later and made it part of American history.

Bettye LaVette sings the song as if she’d just heard it, out of the blue, and couldn’t not but put her voice to it, as if no one ever had. There’s shock hiding in the burr of her voice, as if she’s seeing what she’s singing about for the first time, as if the bulging eyes and the twisted mouth were never quite as real for her as they are now.

This year the House passed Bobby Rush’s anti-lynching bill 410-4; with the backing of 99 members, it was set to pass the Senate in June when Rand Paul put a hold on it (he wanted to make it “stronger,” he said, but that was complicated, and — ). The bill remains in limbo. There’s so much more to focus on: the virus, the next relief bill, federal agents in disguise disappearing people into unmarked cars, but Rush has a record of persistence. He was a founder of the Chicago chapter of the Black Panthers; in 1992, decades after the murder of Panther chairman Fred Hampton by the Chicago police, he was elected to Congress. I will never forget the little item in the paper about his being challenged in the 2000 Democratic primary by a former editor of the Harvard Law Review. “What a carpetbagger,” I remember thinking. Rush defeated Barack Obama by two to one.

3. Mekons, Exquisite. A socially distanced album, or in Mekon Jon Langford’s words “long distance file sharing: Sally and I in Chicago but did not meet up during the process. Tom was looking after his Dad for much of it down in Sussex with only a cell phone. Rico in Aptos CA. Steve played drums in a basement in Brooklyn into a cell phone. Susie and Lu on either side of the Thames — not meeting up as Susie and her husband both had full on COVID. The saving grace was Dave Trumfio our bass player isolating in Silver Lake with a full recording studio so he was the final stop for all the files. I decided to see what I could do with my phone to encourage the others even though I have a home studio in the basement.”

What they came up with is stirring and incomplete. “Nobody,” with Tom Greenhalgh leading, calls back the despairing isolation of “King Arthur” in 1986 — there it was political, here it’s a social, physical fact that won’t hold still. The song is like its own lost chord, drifting too far from the shore: it’s scary. But “What Happened to Delilah” is the other side of the story: quick, a leap, another leap, a punk ring shout, first made of affection between friends, then a sign of community.

4. Peggy Noonan, “The Week It Went South for Trump,” The Wall Street Journal (June 25). “The real picture at the Tulsa rally was not the empty seats so much as the empty faces — the bored looks, the yawning and phone checking, as if everyone was re-enacting something, hearing some old song and trying to remember how it felt a few years ago, when you heard it the first time.”

5. Eric Church, “Stick That in Your Country Song” (UMG Nashville). Can you be cool and inflamed at the same time? This is Church’s “Born in the U.S.A.” written in 2015, recorded in January, released at the end of June. There’s no reference to a pandemic or a man being slowly tortured and killed in public on an American street, not literally, but you can’t not see all or any of that as the song plays. This is the country turning its back on every promise it ever made, until rage rolls over every concise, pungent, necessary argument: “Rock me hard, stop my heart / And blow the speakers right out of this car.” The song gets louder as it goes on, but the real volume is there in the start, the very first time Church spits out the title phrase, so coolly, so inflamed, that he puts a silent word on it: “Stick that in your country song, motherfuckers.”

6. + 7. Lady A, “Dear Fans” (Instagram, and comment June 11). As many have, you can call Lady Antebellum’s announcement that they’d changed their name to Lady A to rid it of the stain of slavery trivial, and you can say they put the name right back when they sued a Black blues singer who performs under the same name. But the Instagram comments following the announcement show it was anything but trivial, this being only one of the more articulate responses (the most articulate was “Bravo!”): “Unbelievable! who exactly are you pandering to? EVERY LIFE MATTERS!! Go ahead Keep the race narrative alive. Sorry I was a fan. Not anymore. Ask the DIXIE CHICKS HOW PANDERING WENT FOR THEM. Good luck.”

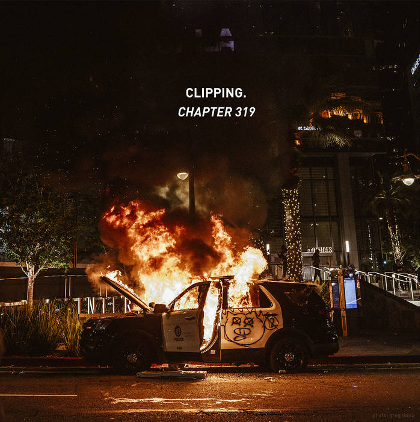

8. clipping, “Chapter 319.” The art for this precise, short, withering stomp by the techno-hip-hop-Afro-futurist-whatever-they-will-not-call-themseves-next trio — Daveed Diggs, voice, William Hutson and Jonathan Snipes, machines — beautiful as it is (and I don’t mean righteous-beautiful, I mean its sleeve art: it’s a perfectly composed image that you can’t help but respond to aesthetically, consciously or not) only grounds the music, it doesn’t speak for it.

clipping is the perfect name for this group: Diggs seems to clip a split-split second off every line-closing consonant, while Hutson and Snipes seem to trim their beats from the front, kicking them forward into the music a split-split second before you’re expecting to hear them. Diggs can rush past his lines — “Fuck the history lesson you know you know by now,” says the man who played Jefferson and Lafayette in the original cast of Hamilton (“The fact that we were all here playing the founding fathers and mothers of this country implies a sort of ownership over our country’s history that I had never felt before,” he’s said). He can bring the song to a halt, a cop flashing his lights and shining his flashlight in its face: “Donald Trump is a white supremacist — full stop. If you vote for him again you’re a white supremacist — full stop.” The record shows up, says its piece, and leaves.

9. Hightown opening credits, produced by Jerry Bruckheimer (Starz). They use “Vacation” by the Textones (the unglossy, unprofessional 1980 recording of the song Kathy Valentine brought to the Go-Go’s) over the opening montage, a portrait of Provincetown, the end of Cape Cod as the end of the earth. You see a utopia of gay bars, fishing boats, transvestites dancing in the street, a multi-sex Poseidon leading a parade and unfolding his arms as if he’s inviting you into the future. It’s irresistible, so sensuous you can’t take your eyes off of it, so fast in its humor — a bag of shrimp is dumped in one quick cut, a bag of syringes in the next — that the very good crime show that follows never quite catches up to it. But the first season only just ended.

10. Ted Widmer, Lincoln on the Verge: Thirteen Days to Washington (Simon & Schuster). American presidential historian, Bill Clinton speechwriter, and Lord Rockingham in the 1990s band Upper Crust, Widmer throws you into a cauldron of jeopardy and suspense and never lets go. Abraham Lincoln is leaving Springfield, Illinois, by train, with Indianapolis his first of the 16 stops it will take him to reach Washington, DC, for his inauguration — if he makes it, if the capital is still there. At the same time, Jefferson Davis is on his own train from Mississippi to Montgomery, Alabama, to assume the presidency of the Confederacy, and if Maryland goes, the government will have to flee. An assassination plot in Baltimore has been uncovered, but not contained, and in fact Lincoln is facing assassination every time he gives a speech, not that the speeches are hobbled and stiff. In Indianapolis, where everything — whether Indiana too might secede — is riding on it, he compares secession to one of the free-love cults that had been outraging Christian society throughout the century. “The refusal to fall apart in 1861 made a difference,” Widmer ends quietly, echoing Melville’s daunting “The Declaration of Independence makes a difference,” just a line in a letter to his editor in 1849. Finally the book is an act of fraternity, subject and writer as democratic brethren — not that Widmer would make such a claim for himself. “It’s definitely about Lincoln,” he says of the 13 days 159 years ago, “but some small piece of this story came from the experience of being in a band, traveling around the country between low-paying gigs.”

Thanks to J.-M. Büttner and Steve Weinstein.

¤

A new and illustrated edition of Greil Marcus’s 1975 book Mystery Train has been issued by the Folio Society in London.

LARB Contributor

Greil Marcus is a critic who lives in Oakland. This year, Yale will publish More Real Life Rock: The Wilderness Years, 2014-2021 (May) and Folk Music: A Bob Dylan Biography in Seven Songs (Fall).

LARB Staff Recommendations

Real Life Rock Top 10: June 2020 — Part II

LARB presents the second, all–Bob Dylan edition of the June installment of “Real Life Rock Top 10,” a monthly column by cultural critic Greil Marcus.

Real Life Rock Top 10: June 2020 — Part I

LARB presents the first part of the June installment of “Real Life Rock Top 10,” a monthly column by cultural critic Greil Marcus.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2020%2F07%2FMarcusColumnJuly.png)