In 2020, chemical pollution leaked into the Compton air, California skies hazed orange with fire and smoke, and a pandemic traveled unchecked across the United States. The same boulevard that holds the annual parade filled with marches demanding justice for police killings. There was no clearing of the difficult rain, no the parade must go on. When will we be together like that again?

¤

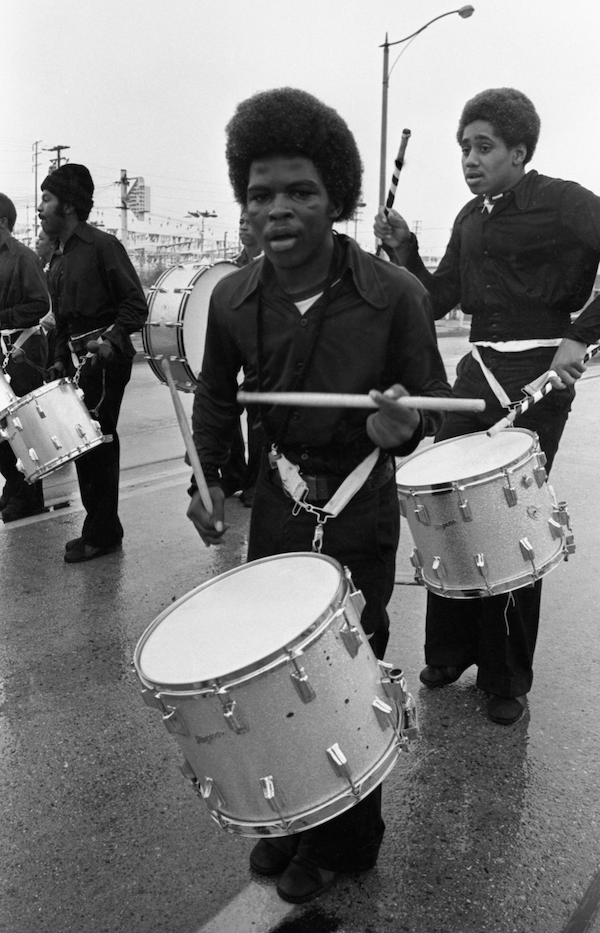

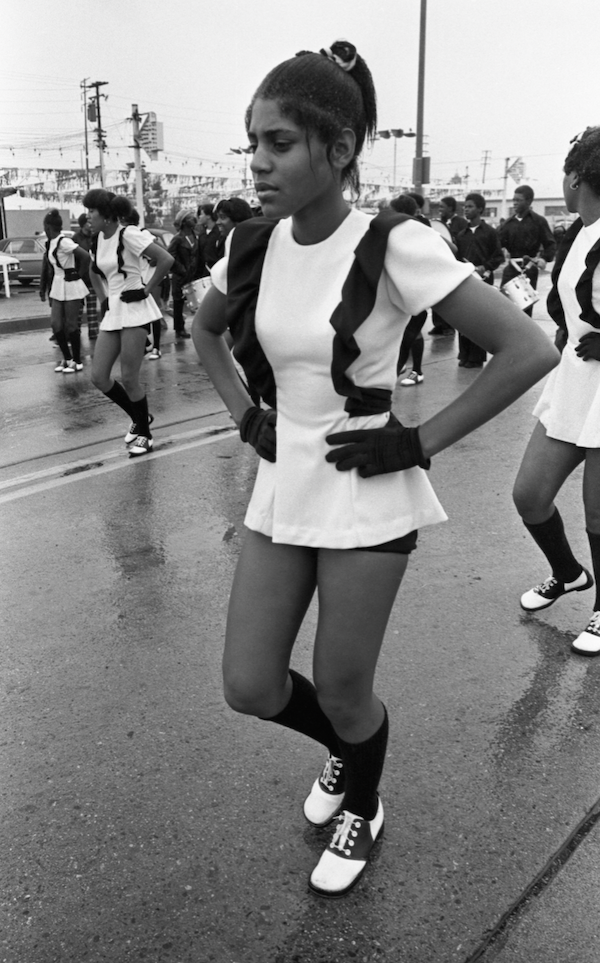

The 1973 Compton Christmas parade faced a hard rain. In black-and-white photos, the event looks like a dream. The sky appears dreary, feels like the blues (despite the lack of color): in each image, it is either raining or has just rained. Yet the parade went on, raindrops baptizing Compton Boulevard as if to mark it as holy. As if there were no rain at all, a gymnastics group marched in sleeveless black shirts, leotards, and tights. One gymnast planted both hands on the slick blacktop, perhaps preparing to do a handstand. Another laid full split on the wet street, chin leaning into the pavement. Their faces could be collaged onto a sunnier day and be just the same.

Newly elected Mayor Doris Davis waved to the crowd outside the frame. She stood beneath a clear umbrella protecting her pressed and curled hair, dressed in a natty double-breasted peacoat with fur trim. That year, Davis won the mayoral election against incumbent Douglas Dollarhide, the first Black mayor of a major city in California. Davis’s victory made her the first female mayor of Compton and the first Black woman mayor of any major city in the United States.

The photographer that day was Guy Crowder, a graduate of Compton’s Centennial High who would become renowned as the first Black staff photographer for L.A. County and as a freelance photojournalist, snapping L.A.’s Black elite for The Los Angeles Sentinel, The Los Angeles Times, Ebony, and Jet magazine. His work included ribbon cuttings, star-studded galas, swearings-in of history-making politicians like Dollarhide, Davis, and Tom Bradley, Los Angeles’s first Black city councilman and its first and only Black mayor. His photos, now featured in the digital collection at the Tom and Ethel Bradley Center at Cal State Northridge, highlight a moment in time when Compton was proudly praised as “the Black city.”

Compton’s Black residents successfully fought to live there. They defeated the campaign waged by its previous majority-White population to keep Black families from purchasing homes in the area, a campaign that involved mob violence, cross burnings, blockbusting, and attempts to reinforce racially restrictive housing covenants that kept Black residents out of neighboring cities like Gardena, Lynwood, and South Gate. While there were some predominantly Black neighborhoods in the region at the time, such as South Central, Watts, and Baldwin Hills, Compton was the only city largely populated and run by Black residents.

By 1973, Compton had an all-Black city council, its first Black mayor, police chief, and community college superintendent. Compton’s Black middle class enjoyed large suburban homes with manicured lawns, ranches with acres of land and stables for horses, prodigious fruit trees, parks with swimming pools, and a shopping district lining Compton Boulevard that served as the backdrop to the annual Christmas parade. The Compton Communicative Arts Academy (CCAA), one of the most influential Black arts organizations in Los Angeles, operated one of many sites on Compton Boulevard and Rose Street. A year later, near Compton Boulevard and Willowbrook Avenue, the city would break ground on the $27 million Compton Civic Center, which included a courthouse and city hall designed by Harold Williams, one of the first Black architects licensed by the state of California.

Over the years, the Christmas parade became a must-attend event. Charles Dickson, a master sculptor and teacher at the CCAA, described the parade as a place where art happened every year. It was a community display of Black culture, art, and performance.

Conceptual artist Lorraine O’Grady understood this when she launched the Art Is… performance at another Black parade in another Black city down another Black boulevard. In response to the notion that Black art was not avant-garde, and as part of several artistic interventions that challenged racism in the art world, O’Grady, who adopted the persona Mademoiselle Bourgeoise Noire, set the Art Is… performance at the 1983 Afro-American Day Parade in Harlem on Adam Clayton Powell Boulevard. On one of the hottest days of that summer, performers hired by O’Grady descended from a float with gold frames in hand. They danced and placed the frames in front of the parade-goers and took their pictures. In response, the audience, shouted, “That’s right, that’s what art is, We’re the art!”

Crowder’s images of the 1973 Compton Christmas parade captured the pride of the up-and-coming Black city. The drumlines, school marching bands, and drill teams were in step with the style of choreographed dancelines and marching bands of the Historically Black Colleges and Universities that many of the Black migrants who settled in Compton graduated from. This would have included teachers I had a generation later: well-dressed, well-mannered, college-educated Black women from Louisiana, Mississippi, and Florida — such as Mrs. Jones, who turned our classroom into a visual and performing arts space, teaching us to make collages from Jet and Vogue magazines, or Mrs. Glasper, who taught us how to balance a checkbook while telling stories about segregation in the South, or Mrs. Booker, who made us recite Dr. King’s 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech and poems by Gwendolyn Brooks and Langston Hughes.

Images of the 1973 parade show a group of drummers with Afros and a drill team dressed in white who look tired and rained-on. Yet they marched on. Another photo follows a white Chevy Corvette Stingray along the glistening pavement, the car bearing a poster that reads “Miss Compton Marjon Battle.” Poet and English Professor Amaud Jamaul Johnson records moments like these about his hometown, Compton, in his recent collection of poems, Imperial Liquor:

Before the wig shops and gutted lots,

Miss Compton’s tinseled scepter, her bob,

A motorcade of Impalas peeling the corner

Miss Compton 1973 gazes toward the camera, T-top windows down, a line of parade-goers on the other side of the street, her smile lighting the way.

¤

Compton’s moniker, “Hub City,” denotes its location as the center of the region. Major north-south and east-west arteries for L.A. County run through it: Alameda Street, home to the once-active industrial corridor that employed many residents in the area; Rosecrans Avenue, which ends mere blocks from the Pacific Ocean; Compton Boulevard, home to the parade, which ran between the city of Bellflower and the border of Manhattan Beach.

I grew up in an apartment building on Long Beach Boulevard, where Saturday mornings the music of Anita Baker, Zapp, Rubén Blades, and La Lupe poured from the apartments of Black migrants from the South and Black immigrants from Panama, like my parents. Long Beach Boulevard, a major thoroughfare that begins near the Port of Long Beach, was a dangerous street. In front of our apartment, cars drove at high speeds, with no streetlights or traffic-calming measures to slow them down. Often, I would hear loud shrieks and would run to the window to see a car accident. Three of my neighbors were hit by vehicles: an elderly woman, who watched me from time to time, gave me rice with sugar and butter when I only knew coconut rice and peas, and two of my friends, one of whom still lives with scars from the accident while the other, a playmate around six years old, was killed crossing the street with an older relative. A crosswalk was painted in front of our apartment building soon after.

The streets of Compton were mostly known for other dangers, as the city became an outpost of a drug epidemic that wrecked neighborhoods across the nation. Surrounding cities, some also dealing with crime and violence, sought to dissociate themselves from Compton. The cities of Paramount, Bellflower, Gardena, Lawndale, Hawthorne, and Redondo Beach all lobbied to change the name of their stretch of Compton Boulevard. Former Gardena councilman and owner of Nader’s Furniture Chuck Nader’s goal was to “eliminate confusion,” a sentiment echoed a year later in Redondo Beach. A Paramount businesswoman complained that Compton was “well-known for the slums and strife that existed there for the last 20 years,” even though Paramount itself had been listed by a RAND Corporation study as one of America’s troubled suburbs several years prior. The unincorporated areas of East Compton and West Compton also elected to change their names; at the time, local officials called East Compton one of the most violent neighborhoods in the area.

Compton City Councilman Maxcy D. Filer, known as “Mr. Compton” because he served as president of the local NAACP chapter and as city councilman from 1976 until 1991, spoke about the race to disown the city’s name: “The city of Compton has a great history,” he said, “then all of a sudden when Compton becomes a predominantly black city, they can find every excuse in the world to take the name Compton away. I just don’t believe their motives.” White residents once fought to keep Black migrants out of Compton; by the 1980s, they fought to make sure the Black city kept to itself. They turned their backs on a city that mirrored their own problems, not recognizing the violence and racism of such an act. Filer countered, “I’m not ashamed of the name Compton.”

The streets and other geographic markers that these neighboring cities renamed into oblivion remain as monuments of the area’s racist past. Homeowners in these other cities would benefit from property values that outpaced Compton’s and perhaps rose at its expense. Decades later, residents from these cities would descend like missionaries with the aim to turn Compton around. East Compton changed its name to East Rancho Dominguez, but their children and grandchildren grew up to say they were from Compton.

¤

Compton Boulevard became a singular road, unique to the city. As Black Studies Professor George Lipsitz observed in his 2011 book How Racism Takes Place, “streets shaped by segregation could also function as sites for congregation”: street parades became a way for “Black expressive culture” to counter the “white spatial imaginary” and create “democratic spaces for cultural production, distribution, and reception.” Every year, residents enact Compton Boulevard as a living monument, a place where it can be itself.

Music has been largely missing from the cityscape during the pandemic. As Johnson portrays the city in Imperial Liquor, Compton is a loud, bluesy place that sways to a constant soundtrack of soul and R&B, narrating love and longing. As he notes in the poem “Smokey,” “the most dangerous men / in my neighborhood / only listened to love songs.”

There is a love song I miss hearing blasting from a passing car or motorcycle (since there was no parade this past year): “Hope That We Can Be Together Soon” by Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes, featuring Sharon Paige. The song opens with what sounds like electric raindrops. Paige, a soul singer from Philadelphia, floats over the melody, articulating the statement and question of the song. This idea of soon reminds me of my mother, who passed away last year, who would say soon come; born in Panama, granddaughter of West Indian Panama Canal workers, she will forever shine in my memory, offering soon come as a future promised, without the assurance of when. I hope that we can be together soon, not knowing when but believing that it is inevitable.

Paige renders the refrain “I hope that we can be together soon” with heart-rending longing. As in the song, there are reasons, known and unknown, why we cannot be together. Paige also passed away in 2020, yet her voice forever shines in these melancholy notes. I hope that we can be together soon, she sings. Real soon.

In the poem “Doo-Wop,” Johnson writes,

the same tune is playing,

as if that cry is holding

the air, as if we are dying,

as if we have never lived.

¤

Compton has tried to change the way it is perceived. At the beginning of her tenure, current Mayor Aja Brown, the city’s youngest mayor, proposed Compton as “the new Brooklyn.” The mayor before her, Eric Perrodin, touted “birthing a new Compton”: the slogan was painted on utility boxes, along with a towering mural of then-President Barack Obama, steps away from the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. monument designed by Harold Williams.

While the myth of the city prevailing in popular culture has been a hindrance to changing the way Compton is seen by outsiders, it remained an asset to those within it. Surviving made you feel you outsmarted danger, made you feel brave. Living here, you believe the hype, even though it may not be completely true, because it grants you a certain credibility. If you can survive here — the outsider’s perception of here — you can survive anywhere. Still, living here gifts a certain tenacity that years and times like this require.

And the Christmas parades continue to draw a cadre of celebrities and artists who are from the city. Kendrick Lamar returned to great fanfare, including a key to the city and an energetic dance performance by local youth, embodying and shouting his lyrics, “We gon’ be alright.” And it is true, as it always has been, for this city — we gon’ be alright.

¤

I don’t know what it’s like to be from a city no one has heard of. When I tell a stranger that I am from Compton, no other reference is needed. It’s real to us, and we call ourselves real, far more than any outsider can imagine. If it ain’t the place to be, it’s the place to be from. I’m from Compton. That’s right … We’re the art!

O’Grady witnessed repurposing of her Art Is… gold frames concept in a Biden-Harris campaign video. Reflecting on the legendary event in her recently released book Writing in Space, 1973–2019, she said: “Although it had been a joyous occasion, it wasn’t the joy that attracted me. It was the complexity, the mystery, the images that no matter how hard I looked, would never become clear, would always remain out of reach.”

What Compton means will always remain out of reach. It is defined and redefined with every generational shift. Upon first glance, the gray 1973 Christmas parade photos may appear unclear, the images hard to see. Performing in the rain had to be difficult, even if the people performing made it look easy. The images reflect that day, that moment in time, in all of its uneasy beauty: people whose spirits refused to be dampened in the downpour.

I do hope that we can be together soon. “Can you make it real soon?”

¤

Compton Christmas Parade 1973

Tom and Ethel Bradley Center Photographs, Guy Crowder Collection

¤

Jenise Miller is an urban planner and writer based in Compton. Her writing and poetry has appeared in KCET Artbound, Boom California, Cultural Weekly, Dryland Literary Journal, and elsewhere.

LARB Contributor

LARB Staff Recommendations

ON LOS ANGELES: Part I: A Downtown in Downtown: Los Angeles’s Manifest Destiny

DTLA 2040 is an ambitious and comprehensive plan to guide the development of greater downtown.

Reclaiming Black Beaches: On Alison Rose Jefferson’s “Living the California Dream”

Eisa Nefertari Ulen considers "Living the California Dream: African American Leisure Sites during the Jim Crow Era" by Alison Rose Jefferson.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2021%2F01%2FMillerTogetherSoon-1.png)