Vanilla with bourbon onion jam, Greek yogurt, and pineapple honeycomb shards: this flavor was never going to be an important “revenue center,” and it was not supposed to be. This is Netflix cheekily playing the merchandising game, getting some “earned media” coverage for their mystery franchise. Netflix has a more cultish culture than the other studios — outgoing CEO Reed Hastings co-wrote a guide to its management style called No Rules Rules: Netflix and the Culture of Reinvention (2020) — but it is not a cult. It knows what it is up to. A little farther south of Van Leeuwen, Netflix was renting out a storefront at the Grove shopping center to sell Stranger Things and Bridgerton merch over Christmas. That might have been more lucrative, or not, but it was, again, promotion pretending to be commerce, dinner-theater franchise-building. (Contrast those efforts with the $500 million build-out of Pandora: The World of Avatar at Disney’s Animal Kingdom.)

Such faux-mercialism is directed at a broad audience, but only incidentally, and the most extreme instance turns decisively inward. In 2018, Netflix spent $150 million (or more; reports vary) to buy a few dozen billboards in Los Angeles, mainly on the Sunset Strip. It did not buy dozens of billboards in other markets or dramatically increase its per-picture promotional budget in outdoor advertising or other media. Netflix was not becoming a “normal” studio. The company’s outsized stock price depended on there being something unique about it, that it was a tech company, headquartered in Silicon Valley. Really. At the same time, it was advertising its movies and shows in Los Angeles so that when the people who star in them or who work on them or who work for Netflix or who might one day conceivably possibly work for Netflix — when those people drove around the city, they would see proof that Netflix was a normal studio. The kind that has franchises and merch and ad campaigns. And one of its flagship franchises is, to get back to the waffle cone, Knives Out.

“Its” franchises. In late March of 2020, Netflix spent roughly $450 million (plus the cost of the movies? again, reports vary) to buy the rights to two sequels to Rian Johnson’s Knives Out (2019). Hollywood was agog, to put it mildly. An anonymous losing bidder told Variety: “The math doesn’t work. There’s no way to explain it. The world has gone mad. It’s a mind-boggling deal.” That spring, Netflix co-CEO Ted Sarandos zoomed into my undergraduate course on Netflix and calmly explained the extremely rich Knives Out deal to my students by saying that it was rare to find “a franchise in the wild,” meaning one not already attached to a major media company. That is undoubtedly true but raises the question of why this franchise was worth that much to Netflix.

The numbers: As mad as it sounded, the Knives Out math might work. Here is a rough version. Netflix spends $450 million and gets two movies (so, $225 million each, perhaps plus production and translation and marketing costs; we’re being very rough). Netflix’s “average revenue per member” in the United States is about $16/month; it is less in other regions. If each movie leads to roughly 14 million “months” of subscription (at US rates), it breaks even. That could be 14 million people who sign up for Netflix in December and then cancel or 1.2 million people who sign up in December and forget to cancel for a year or somewhere in between. With 2022’s Glass Onion, about 16.5 million US subscribers watched the movie on TV over the Christmas weekend, according to Nielsen; more people will watch it later or watched it on another device; some — more than a million — went and saw it earlier in a theater, an instance of faux-mercialism dangerously close to being a real business.

There are about twice as many subscribers in the rest of the world as in the United States, and by January 17 of this year, according to Netflix, about 123 million subscribers worldwide had watched the movie. Although we don’t know the territorial mix of those viewers, Netflix does. Netflix also knows what else Glass Onion viewers watched in December, and what they watched in November and will watch in January, what they watched when they signed up, and so on. They can formulate a very, very good answer to the question of whether the movie was worth it. Whether that $450 million might have been better spent on something else is another question. But it is not implausible that Glass Onion got several million subscribers — ideally price-insensitive subscribers in the United States and Europe — to sign up for Netflix or to fire up a neglected subscription to watch with the fam. And once someone has signed up for Netflix, the cost to keep them around should — should — decrease. End numbers.

Everyone who is trying to think about contemporary Hollywood as a business these days eventually asks what will replace superhero movies as its core franchises. On the one hand, this question neglects all the other supergenres that are currently grinding out successful sequels — action, fantasy, horror, comedy, children’s animation, and others — but on the other hand, it underestimates what the role of the superhero franchise is. If one thinks of the franchise as the flywheel of transmedial synergy — the thing that can generate profitable content in theaters, on television, as video games, at theme parks, in books, as comic books, as consumer goods, and maybe in the frozen foods aisle — then there are not many plausible candidates to replace the superhero movie. There are the space operas, although the Star Wars franchise has had its struggles. Avatar is plausible. And there are the animated movies such as the Despicable Me–verse (Minionade? The Gru-pon?).

But if one thinks of a franchise as a plannable source of content that can “throw off” multiple revenue streams, then Netflix is not in the franchise business in the way that, say, Disney is. I have argued (for Los Angeles Review of Books) that the central corporate question at Disney is how to “proper[ly] articulat[e] audiences in time and space,” how to “allocate and monetize [degrees of] bodily presence.” In practice, this amounts to providing the right amount of intimacy or intensity to convince people to spend as much money as possible — to correlate audience intensities with jumps to more expensive tiers, from cable to Disney+ to a day at Disneyland to a Disney Vacation that might cost thousands.

At Netflix, for now, the central corporate question is how to calibrate audience intensity as viewers alone. In practice, this amounts to generating exactly the right amount of interest to convince people to sign up — or not cancel — next month. If people get more value from Netflix, the company has always said, they can raise subscription prices. If there are people who don’t get that much value, then perhaps they leave or perhaps Netflix rolls out a cheaper, ad-supported tier for them. But whatever Netflix does, you can’t really spend more than 20 bucks a month for it, and they can’t really get more than about 20 dollars in value from you. You can’t get so excited about Wednesday (2022) that your Netflix bill goes up. (That’s just “consumer surplus.”)

If the economics of Glass Onion are largely — and intentionally — distracting, is there something in the franchise itself to help us understand why Netflix wanted it? Was there something in Knives Out that made it uniquely desirable? It’s almost too obvious that the dead mystery author in that murder-that-wasn’t-a-murder mystery was in the midst of firing his son (Michael Shannon) because he kept pushing Dad to sell the adaptation rights to the books — something Dad always refused to do. There is a Netflix offer on the table, we hear, but the window is closing. You can take that sort of studio-inception and run with it.

Still, light-touch mysteries are not hard to come by. Every streamer, every studio, has them. Netflix has Wednesday and Knives Out, but it also has the Enola Holmes adaptations (2020, 2022) starring Stranger Things’s Millie Bobbie Brown and The Witcher’s Henry Cavill; it has Omar Sy’s Lupin (2021– ); it has Natasha Lyonne’s Russian Doll (2019– ) and the very silly Murderville (2022– ) starring Will Arnett; it has Adam Sandler and Jennifer Aniston’s Murder Mystery (2019), and in March it will have Murder Mystery 2. Hulu has Only Murders in the Building (2021– ); Apple TV+ has The Afterparty (2022– ); Amazon has Three Pines (2022– ). HBO Max has The Flight Attendant (2020–22) and Velma (2023) alongside its usual darker stuff. Kenneth Branagh’s adaptations of Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot mysteries are on HBO Max and Hulu and fuboTV and Pluto TV and Kanopy. Peacock has Johnson and Lyonne’s Poker Face (2023) alongside library juggernauts Columbo and Murder, She Wrote.

Columbo, by the way, isn’t just a retro fad. It is a huge retro fad, more popular than 98 percent of all TV series, according to Parrot Analytics. And if you don’t have Peacock, you can watch it on Tubi or Roku or Freevee. Columbo is waiting for you.

The point, then, is not that Netflix has a lot of mysteries — Netflix has a lot of everything, and everyone has mysteries. The point is to figure out what mysteries are doing for Netflix. To spoil the answer, Netflix is interested in mysteries because mysteries link two of the platform’s key problems: intensity and discovery.

Intensity first. These days, television industry discourse arranges audience intensity along a continuum from lean-in to lean-back. Friends and Hallmark movies and Real Housewives and episodic sitcoms are lean-back. The general mode of linear broadcast, where one show flowed into another into the news into late-night talk shows, was basically lean back. That model is back. These days, huge swaths of the TV people consume is “free ad-supported television” (FAST): Pluto TV, Tubi, Samsung TV Plus. Even Netflix has experimented with a “linear” channel. Conventional wisdom was that during the heights of the pandemic, audiences wanted more lean-back TV (I know I did). At the same time, conventional wisdom was that audiences paid premium prices for lean-in TV. The trick was to find the balance.

It may be tempting to think that mysteries are attention-demanding, lean-in television — the sort of shows that put you in full-on surveillance mode — but that would be too simple. There are mysteries you can’t solve before the detective (a ride-along; many thrillers and procedurals are built this way). You can be as intense as you’d like. There are mysteries you solve along with the detective, possibly before they do, possibly not. These are “fair play” mysteries, “whodunits.” To be sure, those are lean-in TV, but the degree can vary. If the pathway to the reveal is enjoyable, that can be enough. As Johnson explained to Rolling Stone, “It’s about just hanging out with somebody that you like, and the comforting rhythms of a repeated pattern over and over with a character that you really liked being with.”

Even when the detective at the center is the nearly disembodied intellect of the analytic detective story, you can be confident that all will be revealed at the end. That confidence is cognitively reassuring, but it is also, importantly, ethically reassuring. At moments of profound social crisis, being able to confidently navigate questions of good and evil can be attractive. There are aspects of this in the true-crime boom, and in Johnson’s work. As he put it to Slant:

The whodunit genre is a very morally unambiguous genre. There’s a crime. There’s moral chaos. The detective comes in, who’s usually the benevolent father, and he, through reason and order, sorts everything out and figures it out at the end and solves the crime and puts the universe back to sorts.

Then there are mysteries you have solved before the detective, where pleasure lies in watching them figure out what you already know. These are “howcatchems.” (Philip Macdonald took credit for the coinage in his 1963 omnibus, 3 for Midnight.) Because Columbo is a howcatchem, and because he almost always does catchem, you can lean back a bit. You aren’t working in parallel with the detective, on high alert. You’re just checking his work.

At Netflix, Russian Doll is a show that demands and rewards extreme attention. We see the same scene play out over and over with the slightest variations. Look away and you won’t have any idea how things have gone haywire or what new morsel of information has been dropped. That is maximally lean-in TV. Enola Holmes requires that sort of attention, too, maybe turned down a notch. Glass Onion is a fair-play mystery, and you could try to solve it along with Blanc, but exactly halfway through, everything changes, so you either lean in further or go along for the ride. Johnson wasn’t lying when he said that they went on vacation and made a movie. Finally, the much sillier (and much, much less expensive) Murderville is fair play, too, but you are leaning all the way back; the mystery is merely the occasion to put the guest star through a series of ludicrous improvisations. Mysteries are an occasion for Netflix to collate audiences and intensities in an era when lean-back TV is newly prominent.

Discovery second. Of course, mysteries are about discovery, unveiling, Heideggerian alethia. “I want the truth!” Janelle Monáe demands. But in the media business, discovery names the process of getting you to know about — and watch — something new.

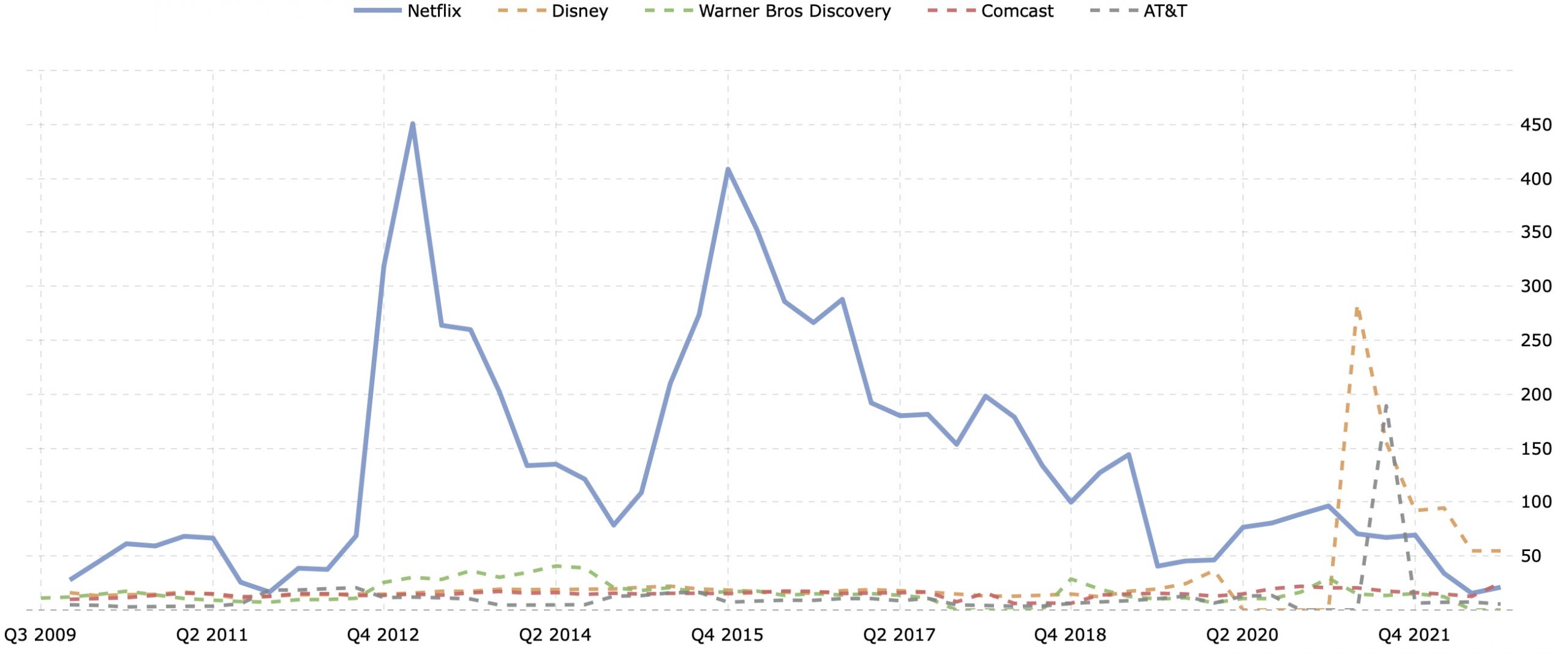

For a decade, Netflix enjoyed a stock price wildly out of line with other studios or entertainment conglomerates, often trading at 10 or even 20 times that of its competition. The assumption was that something Netflix did would mean that it would be vastly more profitable than its competitors in the future. That story was not that Netflix made the best movies and television but that it would find ways to put exactly the movies and TV shows in front of global audiences that they would not otherwise see. And it would do so not by paying for enormous ad campaigns that would (onion) jam that content into your eyes and ears but by surfacing things you didn’t know you always wanted. If things went really well, those unexpected hits would be produced for less. Squid Game is the pinnacle of that strategy.

For that strategy to work, the “product” side — the algorithms that chose the titles and images that would populate the home screen; the teams that came up with the cutesy genre titles; the tweaks like credit-skipping — had to make successful discovery effortless. As Sudeep Sharma described it, Netflix moved from being a library — a repository of every movie ever put on DVD — to being a newsstand — a display of the semi-disposable latest and greatest. One sign of that shift is that the service has trimmed its licensed movie library by more than half over the last decade (although it has grown slightly recently, as What’s On Netflix has tracked). But I would argue that Netflix has moved beyond the newsstand to something else.

At the risk of pretension, I want to say that Netflix’s new strategy is a Fresnel lens: the modifying object that makes lighthouse beams powerful. It is thinner, lighter, and more transparent than an ordinary lens. Easier to fabricate, easier to rotate. Netflix’s new head of creative content, Bela Bajaria, explained the homepage algorithms to The New Yorker’s Rachel Syme in something like these terms: the content “is served right up to you in front of your face, so it’s not like you can’t find it.” No search, just scroll and click. Each subcategory serves a different slice of your possible interests, things at the edges of your vision now brought to the center. Those don’t have to be the latest-and-greatest or the biggest-and-baddest. They might be lower-budget “local” titles (a “retention strategy,” Syme’s article explains), or they might be adjacent in some other way. But whatever they are, however diffuse their origins and diverse their forms, the personalized algorithms are designed to get the right titles “in front of your face,” to get them focused on you. Now.

Glass Onion is unsurprisingly interested in the aesthetics of glassware. Its actual Fresnel plays an important part. When the lights go out on the private Greek island, the guests run and scatter, periodically (and impossibly) illuminated by the lighthouse as it rotates. The scene is replayed at length 40 minutes later, once the plan of Daniel Craig’s Benoit Blanc and Monáe’s Helen Brand has been revealed. There are also key set pieces that include a huge CG “glass onion” atop the estate of Miles Bron (Edward Norton); personalized cocktail glasses for the guests; a roomful of kitschy crystal “art” that is forever getting between the camera and the stars; and a protective glass box designed to safeguard Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa.

While there is a lot of discussion about layers and spirals and whatnot in Glass Onion, the actual glass onion that John Lennon is singing about over the end credits is an old-fashioned bottle with a long neck and a bulbous body. That “glass onion” is not about layers but about distortion. Lennon was admonishing Beatles fans to stop looking for clues, to stop trying to make everything fit (“trying to make a dovetail joint”). Obviously, Johnson knows this. At the crystalloclastic climax of the movie, Monáe and the cast of “shitheads” smash the sculptures and anything else that can be smashed. This catharsis frees them all. It allows them to tell Norton what they really think about him, to embrace the “radical candor” that Hastings made so much of. No more distortion; just transparency. Shattered art and battered industry, in perfect harmony.

Hastings is stepping down now that Netflix’s tech-company valuation is gone. Its stock looks a lot like that of its competitors. One can view that decline as the failed promise of another tech giant that believed its own hype about being “klear.” One can also view it as the inevitable outcome of Sarandos’s project to remake Netflix as a real studio. Fading tech cult, or the ultimate comeuppance for the strivers who have been faking it until they make it? Scientology or UCB? As Norton’s Bron says, and says more than once, “Pick your poison.” Don’t forget the waffle cone.

¤

J. D. Connor is an associate professor of cinema and media studies at the University of Southern California. He is the author of Hollywood Math and Aftermath: The Economic Image and the Digital Recession (2018) and The Studios After the Studios (2015).

LARB Contributor

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Half-Century in Bullshit: On Peter Bogdanovich’s “Paper Moon” and Robert Greene’s “The 48 Laws of Power”

Paul Thompson examines the metabolization of bullshit into our lives, by way of analyzing Peter Bogdanovich’s film “Paper Moon” and Robert Greene’s...

The Funnel and the Horn: On Reinventing James Cameron’s “Avatar”

J. D. Connor analyzes how cultural shifts in the relationship between movies and money made James Cameron’s initial record-breaking blockbuster...

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2023%2F02%2FGlass-Onion.jpg)