Some nights, when the music’s pounding, you can almost forget …

I.

THIS MONTH, James Franco and Travis Mathews bring their bizarre making of/reconstruction of the William Friedkin/Al Pacino behemoth Cruising to OutFest in Los Angeles. Interior. Leather Bar is about 60 minutes of backstage semi-drama: ponderous musings on sex, normality, and celebrity are interspersed with blowjobs and blue-tinged dance scenes. It purports to reimagine the sexually shocking 40 minutes Friedkin cut from the original film, a procedural in which Al Pacino plays rookie detective Steve Burns who goes undercover in Manhattan’s leather bars to catch a serial killer of gay men. The film’s alteration, goes the story, was meant to appease the MPAA and secure an R rating, but on the whole that element amounts to under 10 minutes of recreated footage in Interior, and the real focus lies elsewhere. The filmmakers are aware of this slight of hand, stating that the project is difficult to classify: not a remake, not a reconstruction of missing footage, but a metameditation on Cruising, sexuality in film, celebrity, and the convolution of the creative process. Like its inspiration, Interior asserts — repeatedly — that it is an artistic exploration with nothing to say about the group of people it represents. But unlike its predecessor, Interior says these things out loud.

Franco, Mathews, and Val Lauren — the actor who must reinterpret Pacino’s role as Steve Burns — play themselves in the film, but in an opaque way that begs the question of just whether they’re acting or not. It’s not clear to the viewer when the cameras are capturing unscripted moments, so the boundaries between reality and fiction are hazy, another feature that would seem to connect Interior to Cruising, whose extras were not actors, but patrons of the gay leather bars Friedkin stumbled upon. Interior’s trio, and extras, discuss the place of gay sex in mainstream media, their proximity to kinky gay sex acts, and even the general cloud of confusion that envelops the entire project. In short, they talk about talking about the process of making a film about making a film based on another film. And whether or not James Franco will get naked in it.

Mathews is the only one who seems in his element (with the possible exception of harness-wearing leather daddy Master Avery), negotiating scenes with his actors and offering succinct responses to Franco’s diatribes about artistic freedom and his distaste for the ways in which his “mind has been twisted by the way the world has been set up” around him. Otherwise, nobody really knows what’s going on, and nobody knows what Franco wants, including Franco. It’s as if everyone involved is simply along for the ride, helping him realize his vision, whatever it may be. This confusion, coupled with the film’s focus on Lauren’s discomfort with the project (affectionately referred to as “the Franco faggot project” by his agent) and his loyalty to Franco, is what makes Interior not a reinterpretation so much as a film substantively like Cruising in a number of ways, but mainly through an emotional tie that centers on the ways in which straight men sort through sexual confusion and repression.

Cruising is a fascinating cultural phenomenon, both for its emotional tone and for the story of the failed communication between Friedkin and the gay rights groups protesting his making of it. The film is often eclipsed by an oversimplified account of a then-nascent gay rights movement’s outrage over it, as well as Friedkin’s cavalier and defensive responses to this outrage. But sometime in the mid-’90s, the outrage faded and the film was reclaimed as a campy, archival oddity: a celebration of pre-AIDS New York and sexual freedom. The protesters were recast as finicky prudes uncomfortable with off-the-beaten-path expressions of sexuality, and in large part the homophobia and hatred that saturate the narrative faded from view. Protested and reclaimed: this dual story of Cruising’s reception has been reproduced ad nauseam and it seems fit that we find other ways into this film that seems to have been discussed into the ground and out of relevance. With the Franco/Mathews revival of the questions raised by the film, and also by its making, it seems particularly important to complicate Cruising’s history and to avoid approaching it with either/or questions.

Overall, Friedkin and Franco are concerned with their own relation to queer sexuality: what dealing with the subject matter will do for them career-wise, and their rights to it. Friedkin repeated over and over that the gay world of leather was an interesting “backdrop” and that he had the right, as an artist, to use it as such, while Franco refers to gay sex as a “useful storytelling tool” on multiple occasions in Interior. They both renounce their personal agency in relation to these films, but that doesn’t mean their products aren’t saying something.

Rather than just looking to the imagery, then, it might serve us better to listen.

II.

My first musings on Cruising found their way onto paper in the spring of 2006 in the form of a somewhat purple essay: “Paranoia, Penetration, Permeability: Processes of Gender & Sexuality Identification in the Slasher Film.” This alliterative atrocity was my attempt to situate the film alongside Texas Chainsaw Massacre (Tobe Hooper, 1974) and Halloween (John Carpenter, 1978), and had been fueled considerably by my discovery of Carol J. Clover’s Men, Women, and Chain Saws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film. Her consideration of all kinds of schlock from the oeuvre of Eurotrash maestro Mario Bava to the subgenre of rape-revenge films has come to form the basis for my own academic interests in “bad” film, but at that moment I was simply giddy at the prospect of using phrases like “blood-spattered film screen” and “implied fisting” in an academic context. Cruising — all slick asphalt, spurting fluids, and sexual deviance — was the perfect film to ease me into considering what an abiding affinity for films you’re supposed to hate can mean, and what kinds of thinking that kind of affinity can provoke.

I felt then that the slasher film was an appropriate way to classify Cruising because the film brutally punishes sexuality much in the same way Halloween does. In slasher films, the pool of victims is strikingly homogenous (screaming, sexually active teenage girls and their ineffectual boyfriends), but Cruising goes a step further by suggesting that killers and victims and law enforcement in this environment are an undifferentiated group. Through costuming, tricky camera work, and narrative inconsistencies, Friedkin’s film places all of the men coextensive with Manhattan’s underground leather scene — cops, club-goers, neighborhood dwellers — in the same position: simultaneously potential killer and potential victim. It is implied that the men who cruise are “asking for it” (“it” being a violent, bloody death), and these men are rendered as expendable as the generic parade of girls whose deaths are drawn out and sexualized in slasher films.

I diligently discussed important cinematic components — narrative, characterization, mise-en-scène, and cinematography — in relation to the issues of sex and violence above, as well as the sensational historical context, and proudly handed in my essay on the last day. I still have the hard copy of this paper, and — though my ego is cushioned by the temporal distance between my current self and that earnest 19 year old eagerly applying horror film theories to explicitly queer material — I still feel a brief pang of shame when I look at the red-inked comments and corresponding “B” on the back of the last page. It was my favorite class. I was crushed.

I think that my professor had included Cruising on the syllabus because, well, how could he have left it out? He was probably surprised anyone had chosen to write about it at all. The film has installed itself as an onerous and unfashionable fixture in the history of queer film; anyone who spends any amount of time with this particular canon is sick of Cruising, completely over it and the massive kerfuffle it instigated. It was clear that my professor, upon reading my attempt at analysis, didn’t see much merit there. We had been assigned this wonderful, albeit still mostly depressing, array of films on queer subjects from The Children’s Hour (William Wyler, 1961) and Mädchen in Uniform (Leontine Sagan, 1931) to more modern works, Silverlake Life: The View From Here (Peter Friedman & Tom Joslin, 1993), The Watermelon Woman (Cheryl Dunye, 1996), and Happy Together (Wong Kar Wai, 1997), and I had gone with the most-discussed of the bunch. Cruising had been made by a careless and voyeuristic straight, white man — about gay white men — and I had rehashed discussions of exploitation and representational violence that may have been best left in the 1970s. It wasn’t a bad paper. But, as a current student in a musicology program, I am now aware that there was a particularly glaring absence in my categories of analysis. Narrative, characterization, mise-en-scène, cinematography: this was a mute document, one that suggested that this story unfolded in an eerie silence punctuated only by human voices and the sound of knives entering bodies. A glaring absence, but not a surprising one.

As Claudia Gorbman has helpfully outlined in her book Unheard Melodies: Music in Narrative Film, the structure of film tends to encourage a semi-conscious, intermittent style of musical engagement. The score, especially, must adjust according to other cinematic elements such as dialogue, sound effects, and visuals in order to maintain its efficacy. It is a well-worn truism that once you become aware of the score, it stops working. But the music in the clubs of Cruising — known in film music scholarship as “diegetic” or “source” music — is a prominent feature of the film’s musical makeup. I didn’t really notice that either, concentrating as I did on the erotically charged violence unfolding onscreen. I had also been concentrating on connecting that spectacle — D.A. Miller likens it to a Bosch painting — to the public conflict over representational control that spectacle instigated.

A terminally black-and-white discussion of the politics around Cruising has blotted out the unsettling discomfort aroused by a viewing open to ambiguity and ambivalence, a viewing that considers Cruising in its context instead of jumping immediately to a designation of “good” or “bad.” As I mentioned, Cruising was first decried and later embraced, but this is not the whole story, and it is very difficult for these two reception histories to exist together. For me, though, coming to it decades later, they always have. This is the quality of the film that draws and holds my interest: that it can be both so denounced and so embraced. It is a deeply fractured and flawed object: two films unhappily coexisting in the same insufficient, poorly handled cinematic space. It’s a grim mash-up of film noir and slasher and police procedural, a Frankenstein suturing of ethnographic quasi-documentary to Hollywood thriller, all of which has been cut up, re-edited, censored, and disclaimed in a defensive but haphazard celluloid fission that shot out who-knows-how-many versions into the world. It’s gay Kryptonite, but at the same time, gay time capsule — a sensationalized “based on a true story” plot grabbed from the pages of an equally sensationalized “truth-based” novel (Friedkin’s bread and butter: just look at The French Connection or even To Live and Die in L.A.). There’s a lot going on, but it feels desolate, empty, vibrating with some unspeakable importance. As many have pointed out, it’s simply not a very well made movie. So why bother with it?

Something coheres in the hollow core of this bizarre cultural product, something one can detect in the writings about it, even if one can’t necessarily articulate it. It’s a feeling, more than anything else, one that coalesces largely in my memories of the soundtrack from those early VHS viewings. I remember only two things: the clanking of chains (which was heightened in the soundscape, and which Master Avery recreates in Interior rifling through his suitcase of BDSM gear) as they dangle from a crush of bumping, leather-clad, hanky-coded rear ends, or break the tenuous silence of late-night Manhattan streets and the wobbly Moog drones that mired the urban landscape in a slow haze of despair and decadence. I remember there being music during the club sequences, but any detail was summarily eclipsed by the incredible spectacle unfolding before my eyes: the mass of sweating, hairy bodies, the flashing lights, the leather, the sex. These images, and the unadulterated joy they seem to contain, absorb the vileness in the plot and characterization, soothing the sting of the murder scenes that invariably follow.

III.

Upon returning to writing about the film last year, I realized that the images had absorbed the music as well as soothing the sting, both in the film and in the discussion of the film. Watching again after a hiatus of a few years, I was floored. In 2006, I hadn’t fully thrown myself into an obsession with scores and soundtracks. Back then, I would have noticed a song I liked, but this wouldn’t necessarily have been enough to propel me to the internet to figure out what the song was and how I might acquire it. I was more fixated on gore than score. Now, when about 15 minutes in the first killer saunters past gently swaying meat hooks and the door to the club swings open unleashing the beats that had been bumping away behind the door, my fingers twitched involuntarily in the direction of my laptop. I needed to know what it was.

“Lump,” by P-Funk offshoot Mutiny is the first of many unexpected tracks to grace the soundscape, and it’s tracks like these that are worth discussing, especially since the folks writing about Cruising who choose to mention music can’t seem to get the credits right. Miller, for example, attributes all of the music in the film to The Germs saying “[i]t is scored to terrific original music from The Germs, whose punk pulsations, like everything else here, are too insistent to be just background.” But, though the film’s music producer, Jack Nitzsche, did record six original songs with The Germs, only about one minute of one of those songs — “Lion’s Share” — made the final cut.

Miller isn’t alone in his mislabeling, though, as American Cinematheque publicity for some 1999 and 2008 Los Angeles screenings illustrates: “Featuring a terrific score by composer Jack Nitzsche, with songs by The Germs.” In reality, Nitzsche, with whom Friedkin had worked on The Exorcist (1973), neither composed much of the score nor worked exclusively with The Germs. Instead he pieced together some synth-heavy jazz by Barre Phillips (the source of the droning Moog), repetitive guitar riffs by Ralph Towner, and snippets of Pierre Henry’s musique concrète concoctions. Ultimately, seven artists were tapped for the soundtrack: Willy DeVille, The Germs, The Cripples, John Hiatt, Mutiny, Rough Trade, and Madelynn von Ritz. So much for music “too insistent to be just background.” Reviewers, critics, and research assistants alike couldn’t get their facts straight, choosing instead to praise without specifying sources, perpetuating the relative unimportance of the music as compared with the primacy of the incredible “documentary” images.

But the main criticism of Cruising — that it dehumanizes its gay characters — can be summed up in a music-related question posed by New Yorker critic Roger Angell the week of the film’s release: “Why is the music that accompanies the homosexual scenes, even the casual ones, such persistently loud and menacing rock, while the background score when Steve Burns is in the company of his girlfriend, Nancy (Karen Allen), is a Boccherini violin suite?” Various other reviewers and critics echo the sentiment, citing the loudness of the music as yet another emblem of Friedkin’s dehumanization of the men in the scenes. And it’s true: the music in the clubs is loud and aggressive, insinuating its noise into other parts of Burns’ life. It’s stuck in his head during an intimate moment with his girlfriend, and it becomes part of his daily routine vis-à-vis the radio he listens to as he lifts weights, scowling at his reflection in the mirror.

“Loud and menacing” is a vague and homogenizing description, though, and the soundtrack is anything but. In fact, from Brailey’s chorus of dark, mocking jabs in “Lump” and Rough Trade’s dyke diva Carole Pope sneering her way, arrogant and androgynous, through “Shakedown,” to Willy DeVille’s urban blues growl, and Darby Crash’s adolescent, I-want-it-all screams, the voices populating the soundtrack are a veritable study in the infinite gradations of masculine roughness. And one should also be wary of any formula equating “loud” music with dehumanization and “Boccherini violin suite” with intimacy, and therefore humanity. After all, whenever Burns is with Nancy, the same excerpt from the same movement of the same piece of music plays — a tiresome and inescapable repetition — whereas every entrée into a club is propelled by some new and exciting beat. (I’ll take “loud and menacing rock,” thank you very much.)

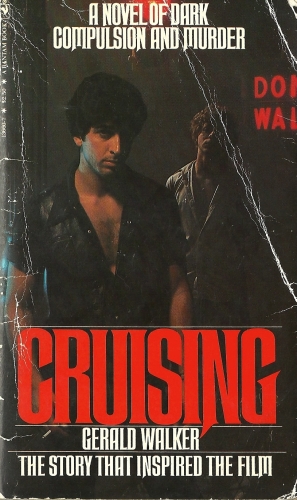

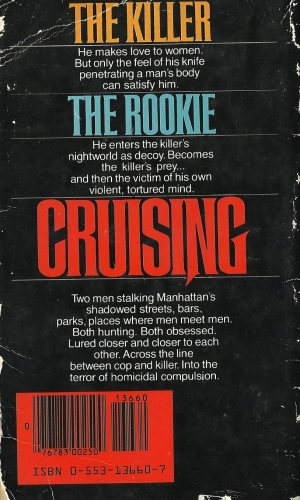

Friedkin was insistent throughout his very bitter, very public debates that Cruising was “real”: that it was based on “real” events, contained “real” clubgoers, and “real” dialogue. But not once did he mention having heard a song included on the soundtrack in one of the clubs he visited. He did hear The Germs play a show in Los Angeles, loved them, and asked Jack Nitzsche to record some new music with them for the film. But this is not to suggest that none of the music had been heard in those clubs — Rough Trade, obviously, very well might have been — but at least a third of that music (specifically, the tracks by Willy DeVille, Rough Trade, and The Germs, and possibly others) had been recorded expressly for use in the film. So where did the music come from? Since Friedkin had decided to scrap author Gerald Walker’s original focus on sandal-wearing, Judy Garland-worshipping sissies — he had, of course, dealt with this type a decade earlier in The Boys in the Band — in favor of the decidedly more macho leather daddy, I doubted that the novel had provided much in the way of inspiration for the film’s soundscape either. But I decided that it was time for me to take a look anyway. So, finally, about a decade after I saw Cruising for the first time, I decided to read the novel, the “story that inspired the film,” as it says on the cover of the paperback copy I picked up.

IV.

My hunch turned out to be an accurate one. The bleak, semi-silent disco noir spaces of Walker’s novel have little to do with Friedkin’s down-and-dirty leather bars, pumping out “loud and menacing rock” in rhythmic waves over a writhing tableau of fisting and fist fights. Why should they? When Friedkin took a look at the script in the early 1970s, he had no interest in it whatsoever. But then he discovered the West Side sex clubs, and things changed. It wasn’t the novel or plot, but the scene that interested him. For this reason, I consider the resulting film an adaptation only in part: more a grafting of reconstituted cinematic neorealism onto a pulpy literary skeleton. If the novel’s tripartite narrative was that skeleton — switching from one first-person speaker to another, police chief to rookie detective to killer and back again — and the voyeuristic gaze of the camera was what fleshed it out, then could I find the acoustic analogues? The acoustic skeleton — a description of the music in the novel — that corresponded with the music Nitzsche grafted onto it? My hopes were not high for unearthing such a skeleton intact.

About 40 pages into the book, however, I stumbled across a musical moment as extraordinary as Mutiny’s “Lump,” the one uncovered by the first killer towards the beginning of the film. Following a description of Stuart’s pathological obsession with film noir, the reader is presented with a more specific description:

His head full of zither music, Stuart loafed out of the movie house with the usual welcome pang. The Third Man always worked for him (this was — what? The fifth time he’d seen it? The tenth?) and he hated to leave. […] The zither music kept going in his head, uninterrupted so far. He knew that Greenwich Village was out there, stiflingly close. He just wasn’t ready for it yet. Nor was the swell of the soundtrack zither ready to release him. All he could do, was glad to do, was hold himself rigidly erect and ride the sound waves tumbling around inside him, alternately speeding and checking his pulse, diddling his senses beyond simple measurement.

I had gone into the novel hoping for subjective descriptions of music in clubs, and I had been presented, unexpectedly, with subjective descriptions of music in film. As I read on eagerly, I realized that film music was being used in this novel to illustrate the interior state of a character, much in the way music is used in film. As Stuart makes his way toward Greenwich Village, his mental meanderings take on an increasingly violent cast; he imagines the inhabitants as akin to vermin that spend the winter “under whatever cover; breeding, endlessly breeding,” and as he gets angrier at the thought of cruising (“What a lot of fuss, Stuart thought, for a little lickie-dickie or whatever”), he both condemns the behavior and blames the participants for his response to them and it: “They might deserve whatever they got, but did he deserve the coarsening that went with giving it?” Stuart alternates between reliving one of his murders, a man named Herbie he picks up in a bar on Third Avenue (no discussion of that bar, let alone the music that might have been playing), and recounting the plot of his beloved The Third Man as he walks, zither music following him down the street like a breeze. And when Stuart begins getting cruised by a dumpy older man whom he nicknames “Dads,” “[a] gust of wind swirl[s] in like a flashy zither attack.”

This particular cue, though it fades away as the novel progresses, gives Stuart a space to project his self-hatred, and in so doing comments, however tacitly, on a kind of personal history of queer engagement with mainstream media, or Hollywood. In his illuminating essay “Homosexuality and Film Noir,” Richard Dyer explores his own affective attachment as a gay man to the genre, and outlines the connection of the representation of homosexuality in general to the genre. He argues that the desolate, alienating, urban mood represented in film noir is congruent with the mood that tends to circulate around the representation of queer characters in mainstream media. Self-hatred, stigma, deviance: all this is contained in a series of moments during which Stuart has a film score stuck in his head, letting it serve as his own soundtrack.

Though the club spaces in the novel and film bear little resemblance to one another, maybe the subjective spaces do, the conceptual spaces meant to directly reflect a character. Nitzsche’s “score” — the one comprised of hacked up bits of other pieces of music, repackaged together — is wall-to-wall plucked sonority. Thus, Stuart’s personal pathology, as manifested in his obsession with The Third Man and its incurably cheerful zither, is warped and projected over the entirety of the world created by Friedkin, a neo-noir landscape to be consumed by new audiences. This time, unlike the situation in the tradition of film noir, the aberrant sexuality is explicit, and it isn’t sublimated through marginal characters, but parsed through the protagonist/antagonist pair, as well as the killers and the victims. The gay nightworld depicted in Cruising, then, despite Friedkin’s defensive declarations to the contrary, is far more than an interesting “backdrop” for a murder story; it is a reflection on the interior conflict produced by a pathologized sexuality. Music plays a central role in the expression of this conflict, but it is generally ignored in conversations about the film and the way it has been received by queer communities.

V.

I wonder what kind of feelings will arise around Cruising now, because of Interior. After all, the summer of 2013 has witnessed a victory in the struggle for gay rights in the form of marriage equality (even though that triumph is not complete, and it teeters precariously against the disturbing gutting of the VRA and threats around women’s rights to bodily integrity, reminding us that rights for some often come at the expense of rights for others). Marriage, normalization — the things that an onscreen Franco frets will neuter a radical queer culture that is, in his words, “actually incredibly valuable” — now seem synonymous with the gay rights movement that feared what a story equating homosexuality with violence might do to public opinion.

But it’s not 1980, and Interior doesn’t threaten in the same way Cruising did; it doesn’t really threaten at all. No one dies because they want sex, and the main gay characters — the couple featured in the most extensive sex scene — are humanized and multidimensional (though I wonder at the reason for centering the most normative pair in a film that wants to trouble received notions of normality). For all Lauren’s worrying that he is participating in a porn flick, the film is being billed as an “experimental” art film, and it will likely be received as such. There are also more options out there for people who want to see films on queer subjects, unlike 1980, when Cruising and its deeply disturbing — but deeply boring — lesbian doppelganger, Windows (Gordon Willis, 1980), were the most visible and accessible options. But the anxiety, the voyeuristic fascination that led Friedkin to don a jockstrap so he could be escorted into The Mineshaft to observe the sordid activities within: that anxiety is clearly alive and well in Interior. This is the fear/fascination dyad that transforms Walker’s novel — which, all things considered, is more a study of men who repress their sexuality than anything else, hateful as it may be — into a confusing cautionary tale about the proximity of homosexuality to death, sexuality as contagious, and a whole slew of other violent stereotypes, and this is why Franco shrewdly states that his making a film like Interior while starring in a Disney film is part of what will give the film its power. The association with kinky sex and gay sex is the thing he will transmit to the mainstream, even if they don’t watch the film. The film itself is somewhat immaterial; the fact that it was made, by Franco, is more important.

Cruising presents a tangled musical world: a film soundscape that draws on a literary soundscape that draws on yet another film soundscape. And Franco’s film adds several more layers: some interesting, some self-indulgent and tiresome. But before Cruising, before Gerald Walker’s novel that rallied the theme song from a 1949 film to tell the reader that the killer was queer? How far back do the connections between media and self go? Cruising presents a very particular representational genealogy, and this is why ultimately, in spite of all of its problems, I cannot leave Cruising alone. It provides an access point not only to the historical facts of homophobia’s construction and functioning in media, but to the feel of that very mechanism. The “movie mood […] less substantial than physical sensation” relied on by Stuart (in the novel) to air his self-hatred, is less substantial than public outcry and defensive response fixed in print, which is less easily dissipated, is one that relies on music — the feelings grafted onto plucked guitar strings and pounding bass lines, sneering and snarling vocals — and the effect of these feelings on an audience.

To return to Roger Angell’s review of Cruising:

Movies are felt by the audiences long before they are “understood.” Going to the movies, in fact, is not an intellectual process most of the time, but an emotional one […] ‘Cruising’ leaves us feeling bad, because it scares us in a dishonest way.”

I’m not sure what Interior does. Franco says that in Cruising, the guy going undercover is portrayed as having descended into an evil place, a dark place, but in Interior, the place, in Franco’s words, is “beautiful and attractive.” To me, the “place” they’ve created isn’t beautiful or evil, it’s just flat, blasé even, a feeling reinforced by the musical choices: uniformly pleasant and driving tracks from A Place to Bury Strangers and Crash Course in Science. No narrative ruptures, no emotional highs or lows, no public outcry: just making a film about making a film that will bring gay sex to the attention of the mainstream because James Franco was involved.

But in an earlier iteration of the project — a trailer for James Franco’s 40 Minutes — we got a reference to Friedkin’s film that seemed to immediately burst the lack of humanity on which Cruising depended: a reference to the sequence in which a number of men cruise Burns in a bar. The camera is positioned at what was, presumably, Burns’s eye-level, seated, and it steadily observes the men passing him by. In this newer take, though, the lens is more focused, tightly zoomed in on the faces of the men cruising the camera, and the sheer diversity of these faces and their modes of cruising shatter the foreboding and monotonous repetition on which Friedkin’s film depended (and personally, I can’t get “Free,” the November Növelet track, out of my head). These shots appear in the final version, at the very end, but the music is different. Why?

Music provides an occasion for self-examination — in both of the films, and in the novel; in audiences, critics, and creators alike — and that occasion should not be taken lightly or ignored. Films like Cruising (based on a novel and the director’s having observed what was going on in leather bars) and Interior (based on Cruising and the discourses of sexual anxiety and artistic freedom around that film) vibrate with histories of conflict. In the rare moments that focus on the specifics and variety of gay interaction, Interior speaks to something larger than the damaging project of using gay sexuality as “a storytelling tool,” a prism through which straight men merely contemplate themselves. If Friedkin and Franco are careless in their deployment of queer communities, individuals, and acts as narrative devices, these communities and individuals continue to deploy and redeploy those very devices, and the traces of that history and struggle will always be felt and heard.

¤

Morgan Woolsey cares about music and identity — and the use of music in disreputable genres of film.

LARB Contributor

LARB Staff Recommendations

Capsid: A Love Song

How to live and love with AIDS.

Shopping and Fucking: “The Canyons”

Looking beyond a world of affectless, trust-funded sexual libertines.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2013%2F07%2F1374097223.jpg)