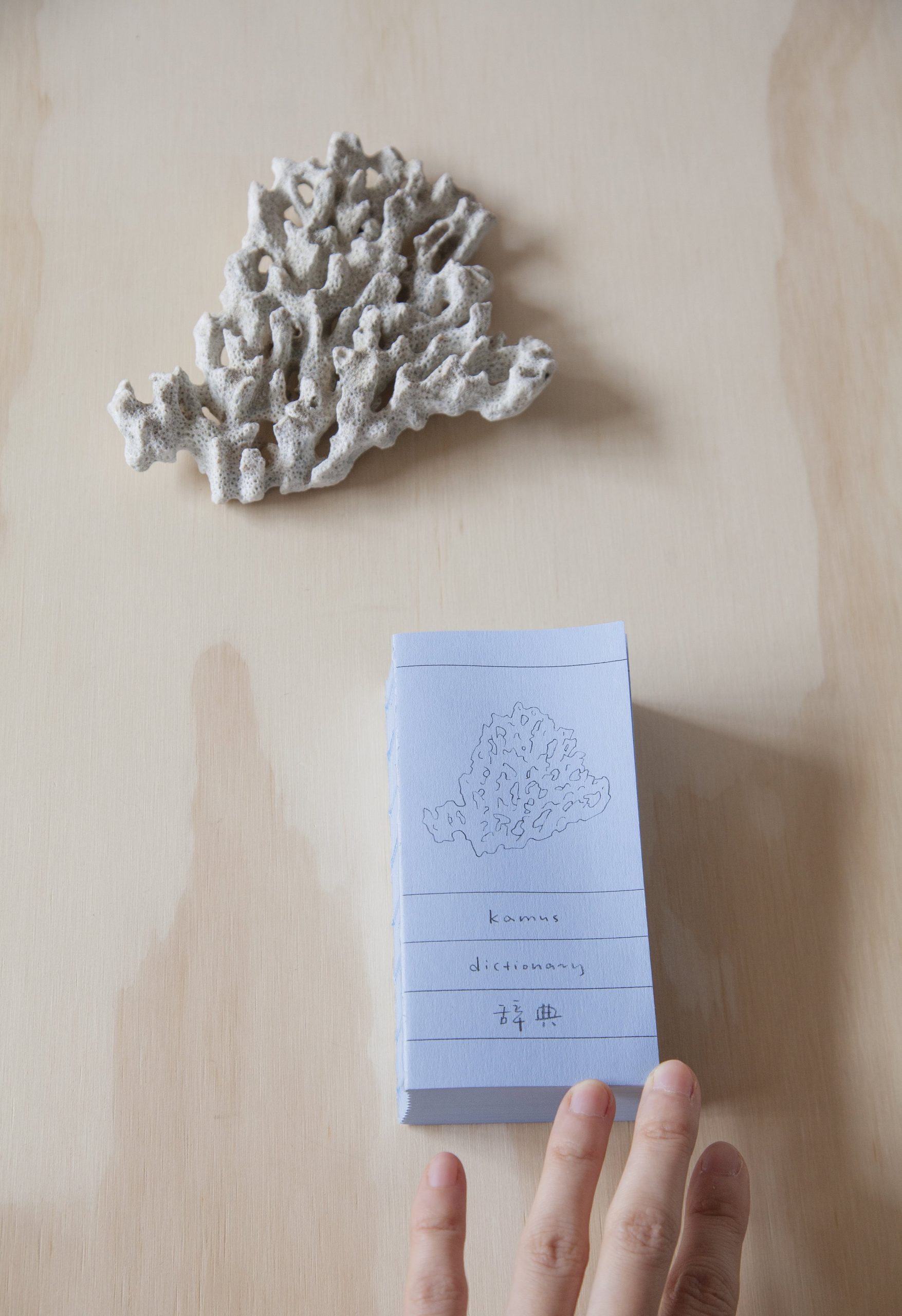

Coral Dictionary Vol. 1: 2019–2022 by Chang Yuchen

While mimicking the didacticism of a traditional dictionary, Chang’s Coral Dictionary is a work that arises out of a series of indeterminacies, haphazard encounters with sites, washed-up pieces of coral, and conversations spoken in many tongues. The text is a microcosm of lived experience, which poetically and persistently constellates a mode of understanding. With Chang herself moving between geographic locations and dialects of Chinese and English, this dictionary is deeply informed by the artist’s own experience of seemingly “always looking for a word.” The artist is neither a person from Malaysia nor a speaker of Malay: her first encounter with corals was during an artist residency on Dinawan, which is surrounded by reefs in a country that is part of the “Coral Triangle.” [2] In performative readings of Coral Dictionary, she has noted how live corals were intimidating to her when she encountered them for the first time while swimming in the island’s warm waters. The corals were bright and teeming with symbiotic and complex ecosystems of life. Communication was occurring in this aqueous hub via chemicals and ocean currents, from polyp to polyp, coral branch to fish, and reef to reef in a language she was an outsider to.

On the shore, washed-up coral bodies, hard and faded in the sun, called to her in a way that was more inviting than their underwater counterparts. Some twisted and some straight, some porous and others solid, these coral bodies, while being biologically “dead,” retained a quality of enchanting expressiveness. The artist’s encounters with these shore-bound coral bodies, along with that chance purchase of a first edition of Kamus Sari and the artist’s own navigations between and through languages and geographies are the genesis points for the Coral Dictionary.

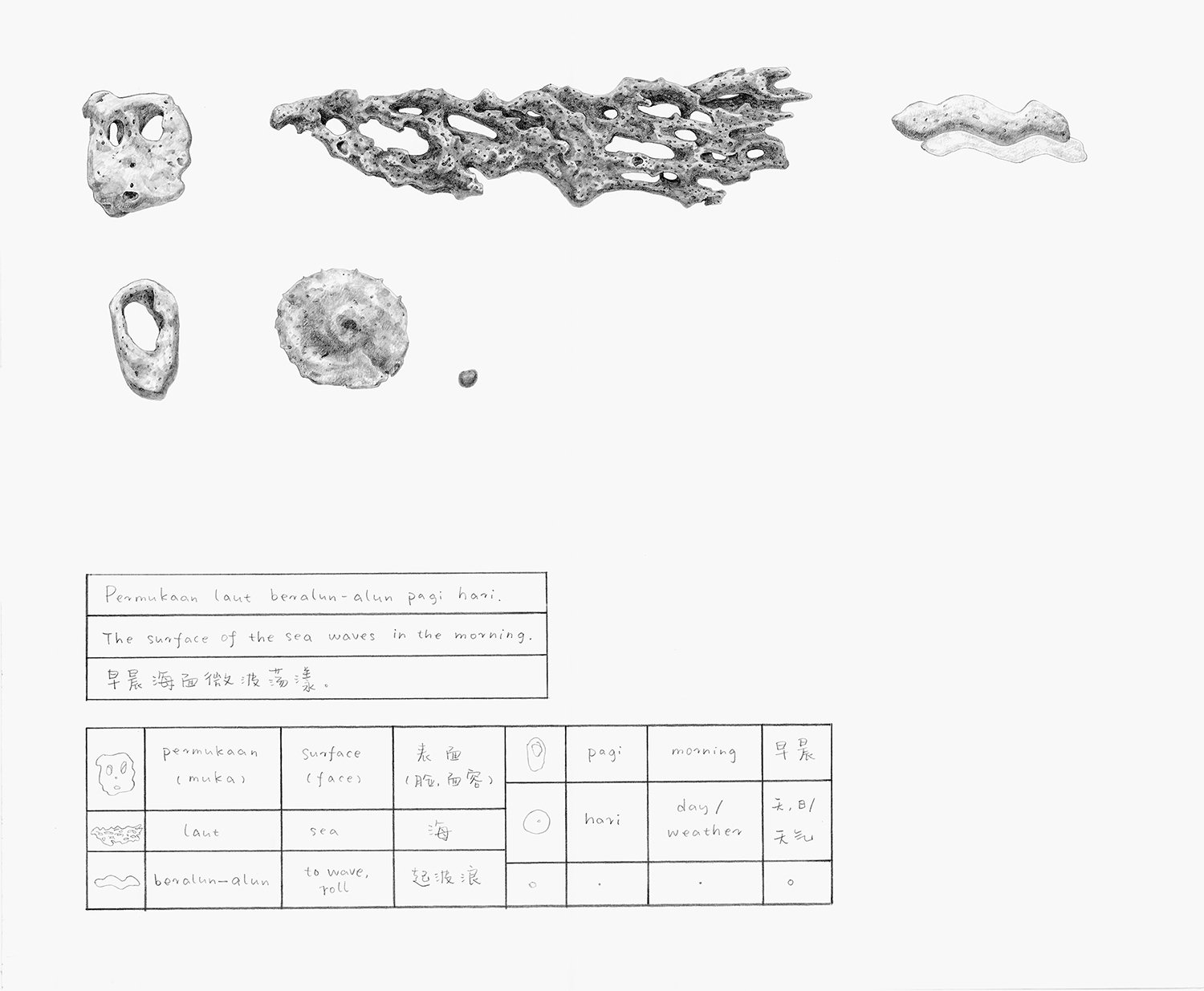

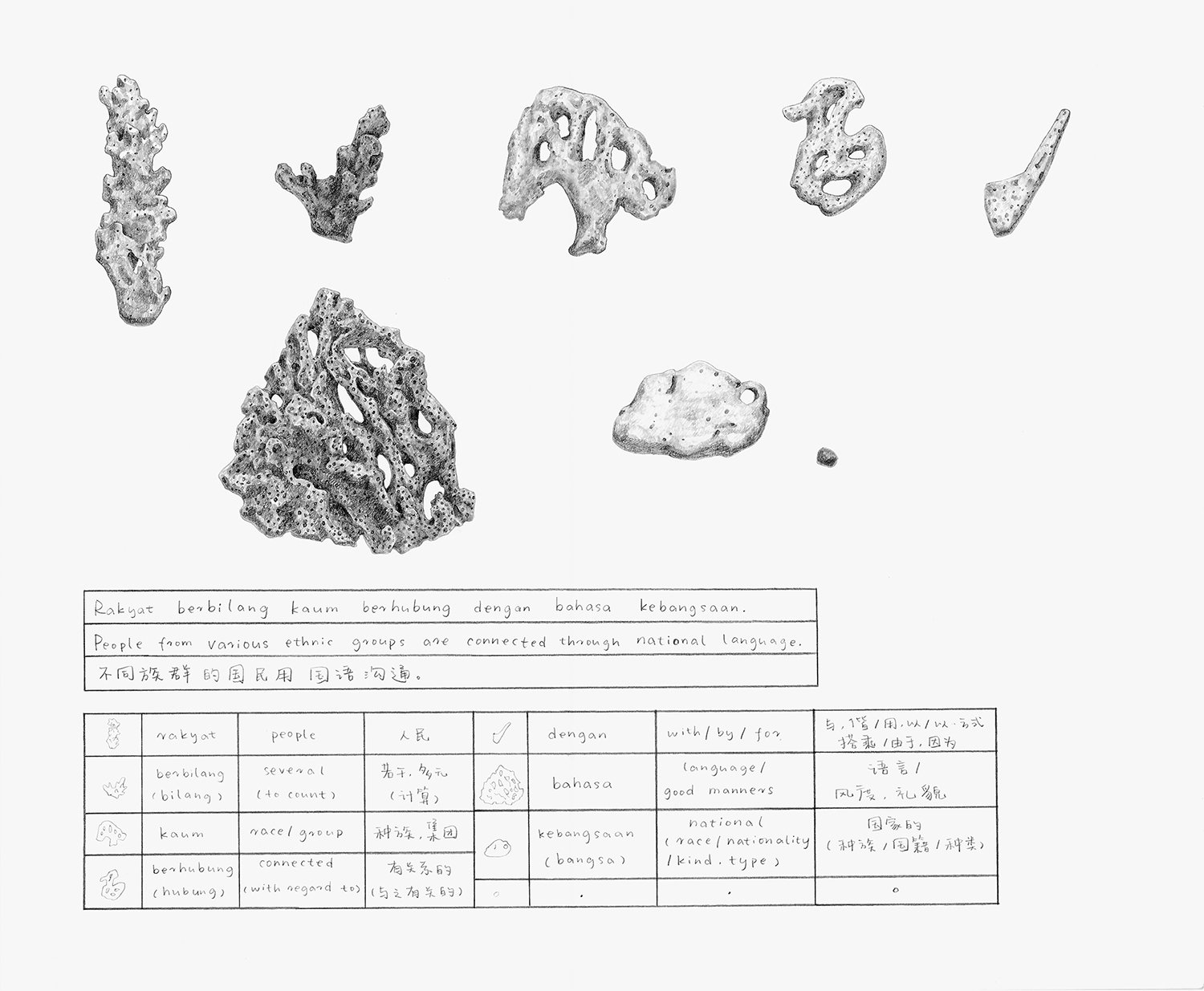

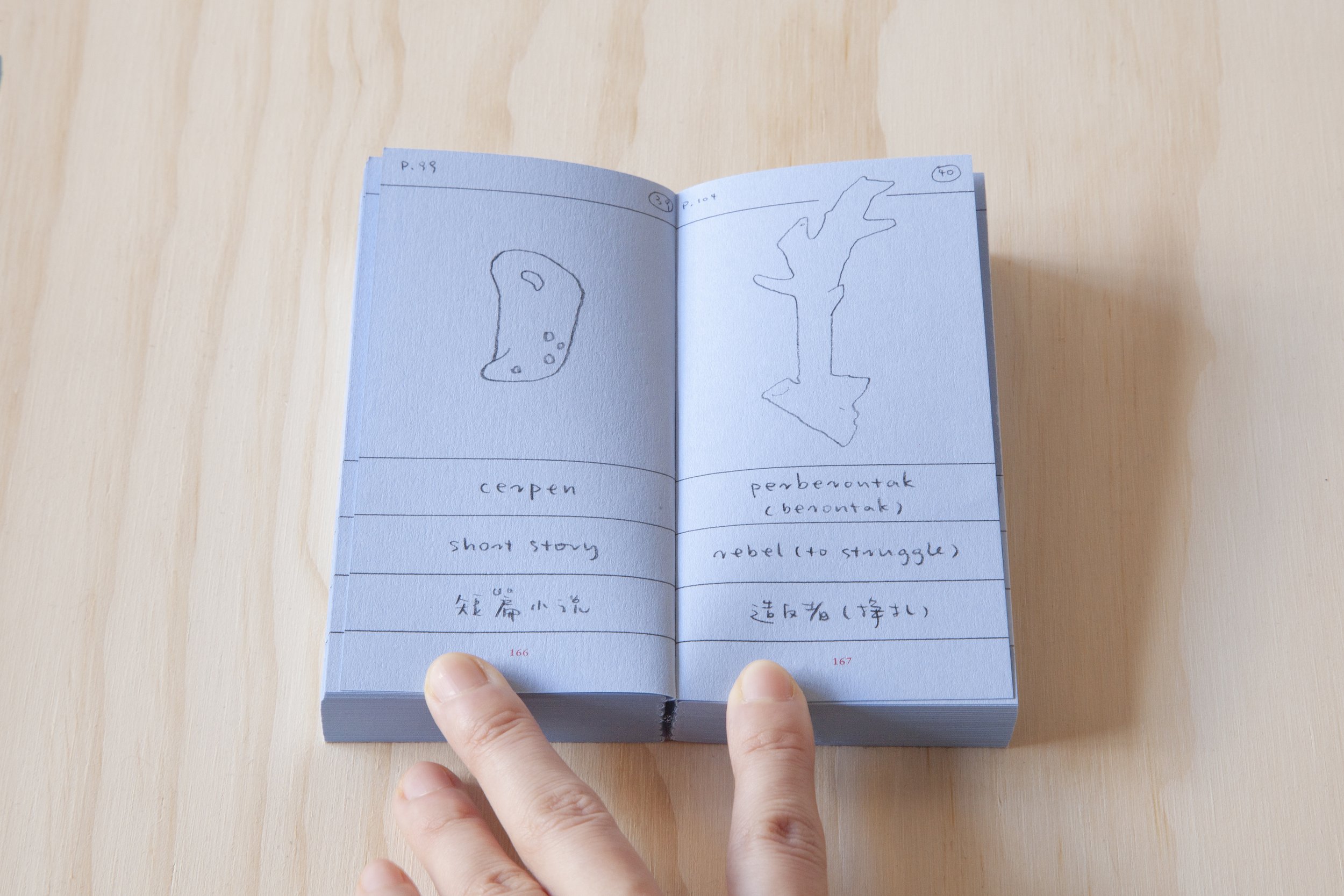

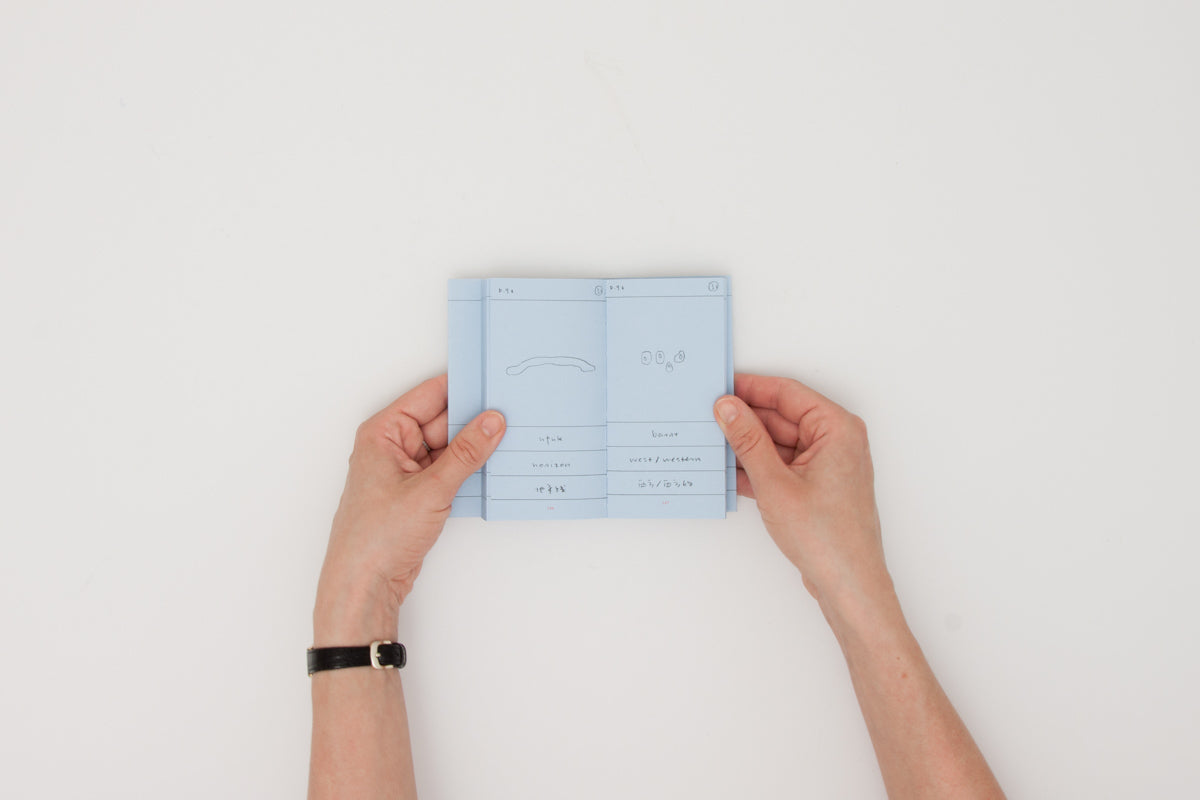

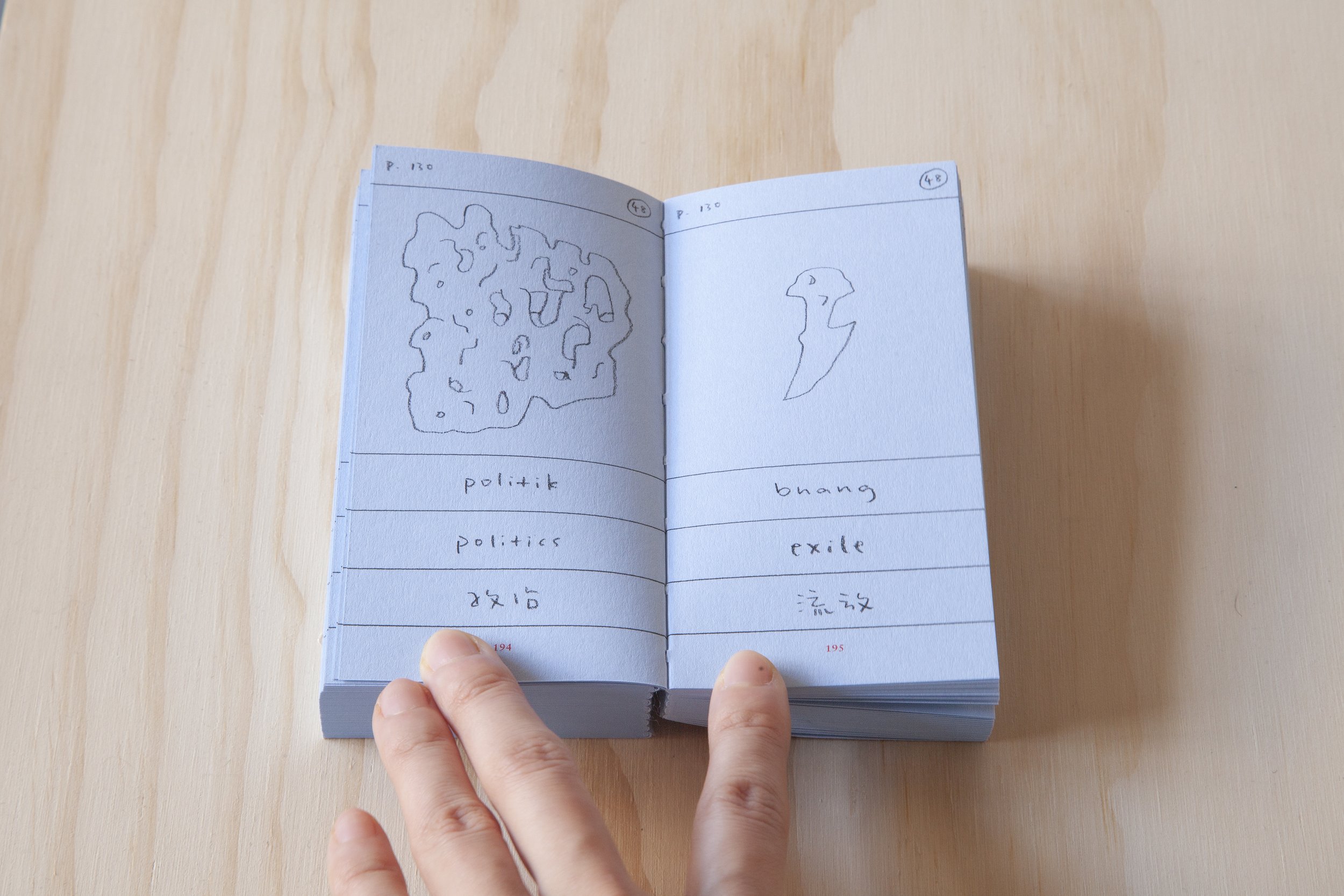

The text does not proceed alphabetically—rather, it follows the translation of a series of sentences selected from the pages of the Kamus Sari. The top corners of each page index the page number of an individual word, as well as numerically indicating which sentence the word belongs to in Chang’s project of translation. At the center of the page, one finds a drawing of a coral fragment, the Malay-Coral word of the individual entry. Below the drawing, the dictionary first lists the Malay translation(s), written in Roman script, followed by an English translation(s), and finally by a Chinese translation(s).

The practice of translating, and the attribution of form to meaning, functions in this dictionary like a series of waves, crashing forward and retreating back again to a larger oceanic body of memory, history, and lived experience. Malay, while having one of the longest written histories of any Austronesian language, does not have its own distinct writing system. Instead, it has adapted itself throughout history to take on various alphabets, including Sanskrit, Arabic, and Roman scripts. This adaptation, as articulated by Alvin Li in the introduction to the text, is a kind of “parasitical rootlessness that suggests at once fugitivity and resilience.”

Chang’s project offers a new poetic and deeply embodied mode of interpreting Malay. Coral Dictionary activates coral bodies (fragments of Dinawan’s island ecology) within the context of sentences that acutely bring our attention to the notion that language, while at times functioning as a medium of universality, is also a deeply grounded phenomenon that weaves together shape and sound, place and meaning. The sentences encountered by the artist in the Kamus Sari do not only provide context for the use of a single word in a phrase. Unlike English’s Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL), there is no established reservoir of didactic materials for Malay, rendering example sentences in the dictionary more imaginative, speculative, and tinged with the particularity of being. These phrases evoke the texture, feeling, and quality of a site and a way of life, effectively conjuring a series of what the artist calls “micro-fictions,” or glimpses into the lived experiences of a place and people’s relationships to land, weather, and each other through language.

Permukaan laut beralun-alun pagi hari. / The surface of the sea waves in the morning. / 早晨的海面微波荡漾。

Kerana kabus puncak gunung itu berbalam. / Because of the mist, the peak of the mountain is blurry. / 因为有雾,远处的山峰模糊不清。

Rakyat berbilang kaum berhubung dengan bahasa kebangsaan. / People from various ethnic groups are connected through national language. / 不同种族的人用国语沟通。

Jangan marah kiranya saya telah lupar. / If I ever forget, please don’t be angry. / 假如我忘记了,请别生气。

Beginning at the level of the sentence, Chang’s project works in reference to her collection of coral bodies in a process that pictographically, tangibly, metaphorically, and emotively reads through her assemblage of coral forms with the goal of finding a word. In non-Roman scripted languages like Chinese, the meaning and shape of the word have always been linked, with characters undergoing stylistic evolutions and simplifications over time. Coral Dictionary puts forward another mode of language development and use that deeply intertwines form and meaning, investigating and probing the limits of what Li describes as the “nature of language and language of nature.”

Laut / Sea / 海 (39) is long and horizontal, taking up two pages in the dictionary. The sea is vast and encompassing. It shifts in hundreds of tiny waves, perforations, and holes as it envelops and carries all in its undulations.

Utuk / Horizon / 地平线 (146) gently crescendoes in two subtle arcs from left to right, the shadow of one horizon appearing beyond the other like an echo, or a ghost.

Untak / for/in order to / 供 / 为了 (18) is almost like a check mark, funneling in a wide opening on its left side to a resting place at its center before rising to a narrower apex on the right side of the coral.

Penbenoutak (benoutak) / rebel (to struggle) / 造反者(挣扎)(167) is rooted in the base of a triangle, erupting vertically to break with the margin line dividing the drawing of the coral word from the indexical reference to page number in the Kamus Sari.

Barat / west/western / 西方 / 西方的 (147) is a word composed of four small oval-shaped corals, each one with a small hole at its center. Placed in a rough line, the third coral dips slightly below the others. Slightly askew from its companions, the idiosyncrasy of this coral infuses the word west with a quality of relationality and contingency. Where we might find west is always dependent on what we/someone else determines as east. [3]

While not following a strict grammatical logic of nouns and verbs, the coral words in Chang’s dictionary take on formal characteristics that are linked to various categories or classifications. Feelings are more ethereal and porous in their shapes. Prepositions are smaller, functional words. Their shapes morph with efficiency from one end to the other, inciting within the artist’s sketched rendering of the coral word the power of inflection held by prepositions within the syntax of a sentence.

Chang is still translating from her collection of coral bodies, working from sentence to fragment and back again. The process is one of constant negotiation and relation between meaning and form. The language of the dictionary is ever-morphing, evolving in response to the corals remaining in Chang’s assemblage. Society is one word that the artist recently tried to find a coral translation for. Initially, she sought to select a large coral, in order to place this word in a category of similar physical likeness to other nebulous and intimidatingly broad words or concepts such as politik / politics / 政治 (194) and bahasa / language/good manners / 语言 / 风度、礼貌 (98). Faced with fewer and fewer large corals to choose from, the artist was forced to reorient her predetermined notion of how society should appear and read. Rather than being sweeping and overbearing in its shape, for an entry in one of Chang’s future dictionaries, society might be found as a smaller body, a piece of coral that suggests communion and collectivity in its shape.

Sitting on a bench in Downtown Manhattan on the hottest day of July, Chang described to me how “language is already a sediment of lived experience; together it weaves a tapestry of a collectively lived experience.” Coral Dictionary Vol. 1 neither prescribes a singular mode of communication nor does it “define” coral bodies and words in the Malay language with heavy-handed rigidity. The spirit of the project is one of generosity and curiosity, drawing upon stumbled and stuttered encounters and a drive to relate to the world and to other beings, both human and not. For generations, corals have been subjects of fascination for humankind, from Charles Darwin’s voyages on the Beagle, which remarked on the growth of reefs and characterized corals as virtuous and industrious architects building for a common good, to Shakespeare’s The Tempest, where Ariel sings of corals as “something rich and strange.” [4] Today, corals are also being read as indicators of climate change, marking in their rapid decay the anthropogenically linked warming and acidification of ocean waters. They are also being read for their genetic characteristics in various scientific research projects on genome sequencing. Chang’s dictionary proposes another, more poetic reading of these organisms, inscribing in the pages of her dictionary a tool for translation, a mode of communication, and an expansive form of relation that, instead of singularly fixing meaning, works to generate openings of understanding. Coral is a threshold for encounter and emergence. As Li writes in the introduction to the text, Yuchen’s project breathes “new life” into these fragmented forms, acknowledging their capacity to be expressive, poignant, and haunting despite being “dead.” Translation, as Coral Dictionary shows us, always moves both ways, receding, swelling, and crashing forward in cycles like ocean waves.

¤

[1] Coral Dictionary Vol. 1: 2019–2022 was published in two formats, one bounded “paperback” volume and another accordion-style booklet. These formats attest to the project’s modulation between its functionality as a dictionary and the more poetic and expansive possibilities the text offers and probes in relation to language.

[2] The “Coral Triangle,” also known as the “Amazon of the Seas,” spans the waters of Indonesia, Malaysia, the Solomon Islands, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines, and Timor Leste and contains over 600 reef-building coral species (75 percent of all species known to science).

[3] As part of his larger scholarly pursuit of “Dislocating the West,” Naoki Sakai articulates this point within in a philosophical context at a lecture at the Inside-Out Art Museum in Beijing: “Neither the West nor the East can be a determinate location; both are a relative designation, so that what is determinate about this relation is the microphysics of power relations that makes the West and the East appear somewhat anchored, natural, or preordained. What makes the West or the East determinate is the very conduct that takes place in these power relations at the very locale in which the West is bordered from the Rest.”

[4] Darwin even went so far as to write in one of his notebooks that “[t]he tree of life should perhaps be called the coral of life, base of branches dead; so that passages cannot be seen–this again offers contradiction to constant succession of germs in progress.” See also Marion Endt-Jones’s introduction to Coral: Something Rich and Strange (2013).

¤

Maya Hayda is a curator, writer, and art historian based in New York. Her research explores materiality, poetics, and the confluences of natural and built environments, particularly across Eastern Europe and the Global South.

¤

Featured image credit: Chang Yuchen, Coral Dictionary Vol. 1: 2019–2022. Courtesy of the artist and Gong Press.

LARB Contributor

LARB Staff Recommendations

Carnivalesque: On the Ways We See Basketball

In a preview of LARB Quarterly no. 39: “Air,” Tosten Burks surveys the new philosophy and syntax of basketball writing.

The Limits of Agency: On Olga Ravn’s “My Work”

Ariel Courage reviews Olga Ravn’s “My Work,” translated by Sophia Hersi Smith and Jennifer Russell.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2023%2F11%2FChang-Yuchen-1.jpg)