Charles Bukowski’s Posthumous Poetry: As the Spirit Wanes, Shit Happens

By Abel DebrittoMarch 2, 2018

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2018%2F03%2FDebrittoBukowski.png)

Out of the 23 poetry collections put together by Bukowski’s longtime editor John Martin, 11 came out while Bukowski was alive and 12 appeared posthumously. The latter 10 posthumous collections, beginning with What Matters Most Is How Well You Walk Through the Fire (1999) and ending with The Continual Condition (2009), were heavily edited. Collectively, they feature almost 1,600 poems, in which, I believe, Bukowski’s original beauty is simply gone.

Much like a seasoned photographer, Bukowski had an acute eye for capturing reality as is, showing things almost without comment in his poetry. Matter-of-fact storytelling was one of his fortes. He also had this uncanny ability to turn mundane, ordinary events into something extraordinary with astounding simplicity — legions of fans have failed at mimicking his apparently artless style. His lines are, for the most part, clear and all too direct, occasionally tinged with lyricism; his words are raw, crude, uncompromising, often touched by humor.

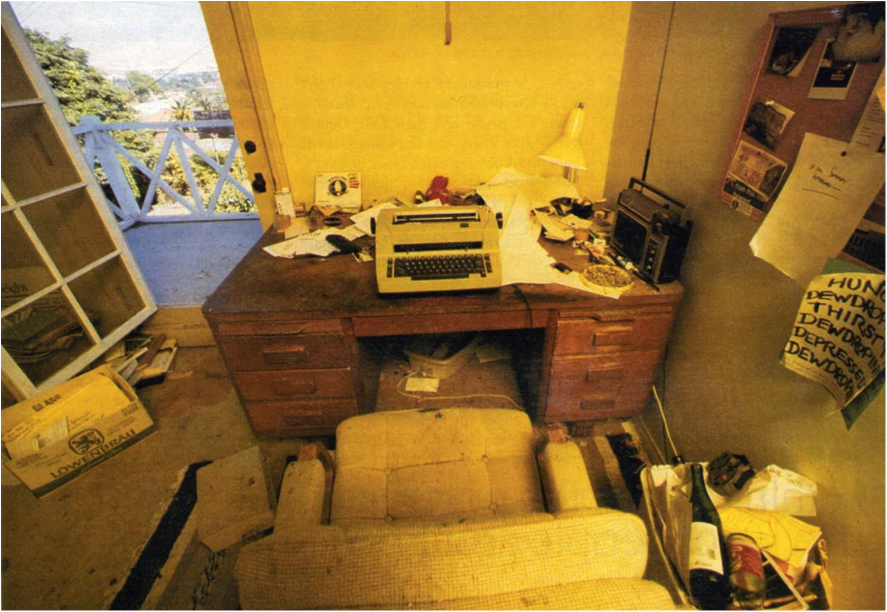

Unafraid, he talked about anything and everything, as if taboo and fear were not part of his vocabulary. Smiling, he unleashed all kinds of hell on the blank page. He deliberately came up with this tough guy image, this Dirty Old Man persona that attracted and repulsed readers equally. Some people were appalled by his seeming obscenity and coarseness, while others embraced his openness and unswerving will to fight the Establishment with his typewriter. Having little time for double standards, Bukowski punched readers in the gut, hit them hard with his trademark uppercuts, making them feel each and every word on the page, spare and simple as they were.

Words did matter to Bukowski, who always said that writing kept him from committing suicide or being locked away in the madhouse. Writing was his crutch, his incurable disease. While drinking the “blood of the gods” and listening to classical music, he wrote furiously almost every day. He was sick with the Word, and the changes made to his poems posthumously robbed his poetry of his natural beauty.

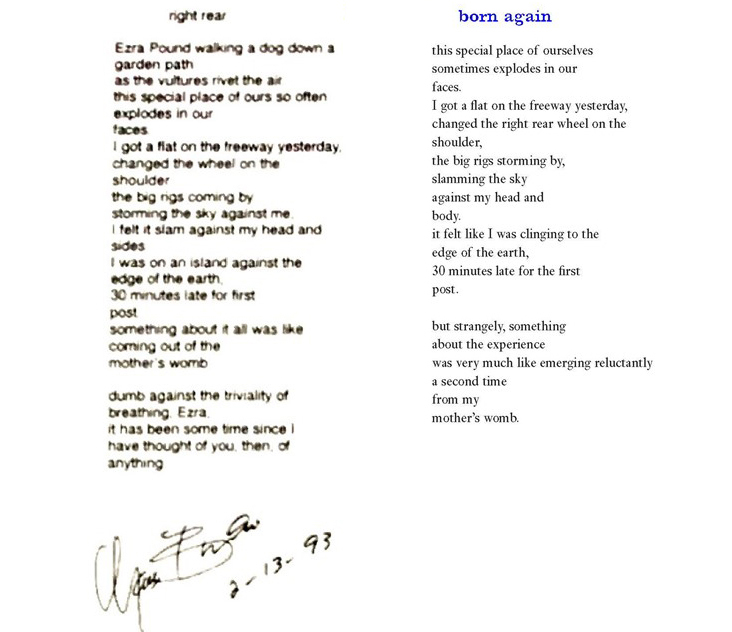

Let’s consider the following poem: first titled “right rear” in Bukowski’s original February 13, 1993 manuscript, it was later collected as “born again” in The Flash of Lightning Behind the Mountain (2003).

[Click here to see poem comparison]

A quick glance reveals that the first three lines are gone as is the last stanza. This is especially egregious because Bukowski looked up to Ezra Pound, wrote many great lines and poems about him over the years, and never willingly removed a single reference to Pound in his poetry. Doing so, as any Bukowski fan will know, makes no sense at all.

Only three lines of the poem remain unchanged, but what makes the collected version so hard to stomach is the final stanza. What Bukowski says quite simply in three lines — like a snapshot in time — is replaced by an attempt at explaining what Bukowski didn’t want to explain.

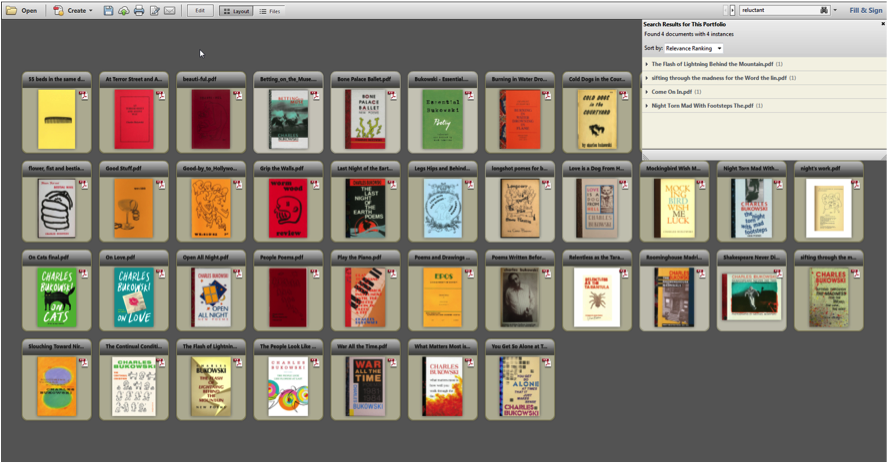

In addition, Bukowski never used the word “reluctantly” in his poetry. Not even once. According to my Bukowski databases — with some 5,800 pages of fully digitized original manuscripts and 3,000 pages of poems published in little magazines plus all the books put out by Black Sparrow Press and Ecco — a search for the word “reluctant” returns only four entries out of the roughly 700,000 words that make up all the BSP/Ecco books:

Upon close inspection, “reluctant[ly]” appears only in posthumous collections. Clicking on one of the “reluctant” entries, we can read in the poem “iron,” published in Sifting Through the Madness For the Word, the Line, the Way, a line about “muscles reluctantly responding,” while the original manuscript for the same poem simply says “muscles respond.” The same happens in the other posthumous instances. The word never appears in the unpublished and uncollected poems I have on file, either.

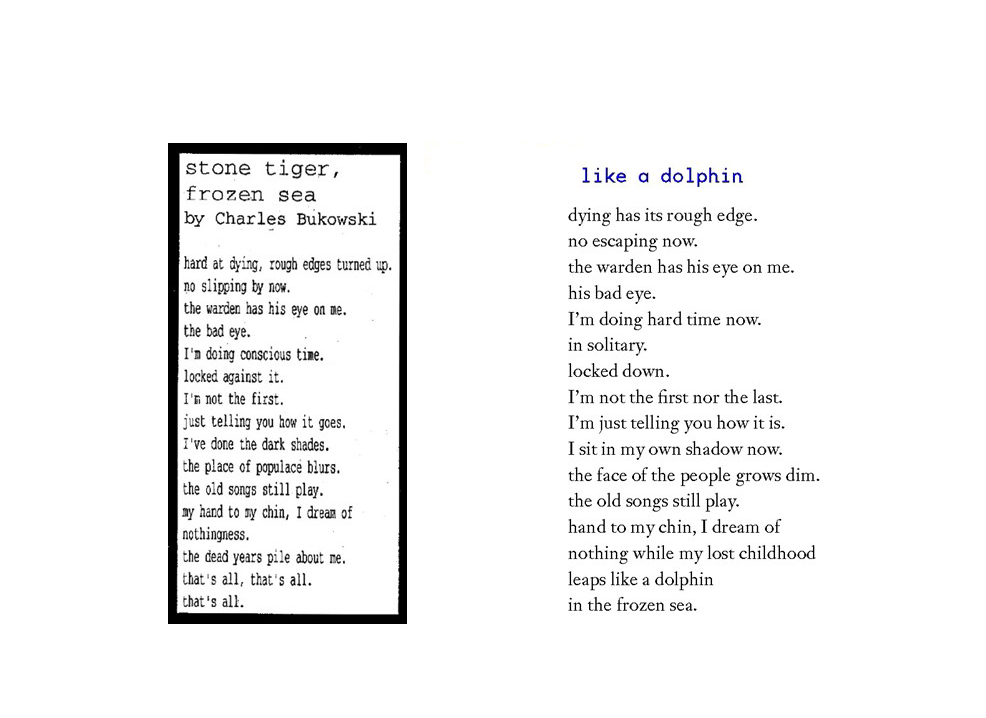

Upon close inspection, “reluctant[ly]” appears only in posthumous collections. Clicking on one of the “reluctant” entries, we can read in the poem “iron,” published in Sifting Through the Madness For the Word, the Line, the Way, a line about “muscles reluctantly responding,” while the original manuscript for the same poem simply says “muscles respond.” The same happens in the other posthumous instances. The word never appears in the unpublished and uncollected poems I have on file, either.Let’s consider yet another example. The poem “stone tiger, frozen sea,” dated July 9, 1992, in Bukowski’s original manuscript, was first published in the little magazine Hype in late 1992 without a single change, and it was eventually collected as “like a dolphin” in Sifting Through the Madness with significant changes.

[Click here to see poem comparison]

Only two lines remain unchanged. This is especially upsetting because the poem was used to close Sifting Through the Madness, and all previous collections were graced by a strong closing poem that readers saw as the icing on the cake. The title itself is eyebrow-raising. Bukowski was not a dolphin kind of guy: in his poetry, we find dying mockingbirds in the mouth of a cat, flies trapped in spider webs, cockroaches and snails climbing walls, but leaping dolphins? A quick search in my databases tells me that the word “dolphin” appears only twice in all the BSP/Ecco books, both times posthumously: in a poem titled “guru,” the “jellyfish” that appears in the original manuscript is replaced by “dolphins” in the posthumous version. The only time Bukowski actually used the word “dolphin” was rather mockingly in a poem titled “we get along.”

The “lost childhood” image that is tacked on in the posthumous version is nowhere to be found in Bukowski’s actual poetry. In his work and interviews, Bukowski talked about his “rotten childhood” and “a twisted childhood [that] fucked [him] up” but never of a “lost childhood.” This unbukowskian image appears only twice in all the BSP/Ecco books and, again, both times posthumously. In a poem titled “explosion,” the original manuscript’s “Europe reaches out…,” is replaced by “my lost childhood reaches out…” It’s true that the original ending lines of this poem were perhaps not that stellar to begin with. It’s quite possible that Bukowski, in his old age, felt there was nothing else to say. As simple as that. The version most readers saw, however, used an embarrassingly trite image to end the poem — and the book.

I’m not cherry-picking here: the researcher in me would like to go on and on, showing hundreds of startling changes, the edits made to Bukowski’s poetry once he was gone. I can’t help but thinking of “bayonets in candlelight,” which runs for 98 strong lines in the original manuscript, and 31 heavily edited lines in the posthumous version printed in The Continual Condition, but I believe the two instances above should be enough to illustrate the extent of the changes that were made to virtually all the poems published posthumously.

Contrary to popular belief, Martin did edit Bukowski’s work when he was alive. When Martin published Bukowski’s first novel, Post Office, in 1971, Bukowski knew it had been heavily edited and almost cut in half. But other than refusing to have a glossary at the end of the book, he didn’t complain. His attitude changed when he received the first edition of his third novel, Women, in 1978. There were so many nonsensical edits that he requested Martin restore the original text and asked his German translator not to translate Women until he received the unedited version. Both complied, and the unaltered edition of Women was soon published. However, Bukowski never complained about the changes made to his poetry during his lifetime. Those edits were minor, and many of them were made by Bukowski himself, who rewrote his poetry more often than is commonly thought.

After Bukowski died, things went downhill. The edits were no longer minor. Some people believe Bukowski deliberately reworked his poetry and put it aside to be published posthumously. This is simply not true: he was a prolific writer, too busy writing new material all the time. As I have noted elsewhere, Martin was entirely responsible for selecting and editing Bukowski’s poetry, including the posthumous collections.

This poses a most pressing question: who made all those changes? I have personally seen all Bukowski manuscripts, typescripts, and notebooks in libraries and in private collections — a few Bukowski collectors hold up to several hundred manuscript poems. Some of those poems do have edits by Bukowski himself — usually dropping weak lines and words and correcting spelling — but I can safely say that large changes like the ones that appear in the posthumous collections were not made by Bukowski himself. For the most part, Bukowski ran away from ludicrous platitudes, overblown imagery, and beside-the-point clarifications. His poetry was clear enough as it was; changing it to explain what Bukowski meant made it pedestrian at best.

When asked about this, Martin didn’t hesitate:

Bukowski could write a poem, send it out where it might or might not be accepted, put his copy of the poem in a pile, and then come back to that poem 4-5 years later. At that time he might scrap half the poem and rewrite the remaining portion into a new poem. Or perhaps revise it. Or he might (or might not) give it a new title. This creates an impenetrable maze.

But the examples above point in an altogether different direction. On another occasion, Martin said that sometimes his secretary at BSP was so bored typing things up that she would “throw things in.”

Bored secretary or not, it’s a moot point now. Pointing fingers won’t change anything. All I can say is that the countless changes that mar the almost 1,600 poems published posthumously were not made by Bukowski. All is not lost, however. Unabridged editions of the posthumous collections, restoring Bukowski’s genuine voice and style, will hopefully appear before long. Storm for the Living and the Dead, available now from Ecco, is the first all-new poetry collection in 25 years to print Bukowski’s work without alterations. It is the first step in this necessary direction.

¤

Abel Debritto is the author of Charles Bukowski, King of the Underground, and he has edited On Writing, On Cats, On Love, Essential Bukowski, and Storm for the Living and the Dead for Ecco. He’s currently working on two new Bukowski projects.

LARB Contributor

LARB Staff Recommendations

Lionel Rolfe and the Rise and Fall of the L.A. Coffeehouses

Anthony Mostrom profiles legendary L.A. bohemian Lionel Rolfe and the coffeehouses in which he thrived.

Blurring the Boundaries: The Poetry of Michel Houellebecq

Russell Williams reviews Michel Houellebecq’s poetry collection “Unreconciled.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!