Three white European filmmakers have dwelled on the superstar’s struggles in separate documentaries released in the last two years, employing familiar tactics of investigative entertainment journalism to either expose “the real Whitney” (in the case of Nick Broomfield and Rudi Dolezal’s 2017 spectacle-driven Whitney: Can I Be Me) or to excavate and ponder the childhood traumas that may have ultimately contributed to her destruction (as seen in Kevin Macdonald’s sensitive Whitney, now in theaters). All three directors are committed to leaving no stone unturned, prodding talking heads to frame their narrative with intimate knowledge, anecdotes, observations, and forging an air of conviction about a subject unable to speak for herself.

Cinéma vérité rock-and-roll exposé has now reached middle age, with its roots in classic “rockumentaries” like Gimme Shelter, the Maysles Brothers and Charlotte Zwerin’s unsettling exploration of the Rolling Stones in 1970. Spoofed mercilessly and with delicious precision in This Is Spinal Tap (1984), it is a genre whose durability continues on in this millennium in everything from Metallica’s masterful Some Kind of Monster (2004) (which carried the psychoanalytic suggestiveness of musician documentaries all the way into the therapist’s office) to more conventional fare extolling the pleasures and pitfalls of fame via the likes of Katy Perry, Justin Bieber, and other pop dreams. We’ve come to expect from these vehicles a carefully curated form of “intimacy,” wherein certain aspects of a musician’s offstage (or “backstage”) world are divulged for public consumption, with women artists facing the particularly sexist demands to “humanize” themselves and appear “approachable” as Houston struggled to do.

Savvy subversions of the form by female artists remain regrettably rare, though our two feminist superstars of the late 20th and early 21st centuries, Madonna and Beyoncé, have each taken shots at disturbing the playbook. The latter’s 2013 HBO special Life Is But a Dream was a televisual selfie made of and for the early iPhone-Instagram era. Instantly irresistible, it invited viewers into the lushly curated yet seemingly quotidian world of an artist who’d largely shut down media access to her personal life years before. An even slyer take on control came two decades earlier when Madonna’s Truth or Dare (directed by Alek Keshishian) turned the genre of musician exposé on its head and effectively kickstarted the reality pop culture era that has saturated our universe for more than a quarter of a century.

A precursor to MTV’s Real World series (which debuted on the network one year later) and VH1’s addictive Behind the Music (which dropped in 1997), Truth or Dare sold a highly stylized spontaneity and (presumably “declassified”) confidentiality (Madonna throwing shade at her straight world boyfriend Warren Beatty; Madonna revealing her secret crush on Spanish up-and-coming actor Antonio Banderas) and aligned with the pop diva’s career-long battle to go against the grain of Moral Majority puritanism. With 1992’s controversial Sex book and 1994’s Bedtime Stories album (featuring the teaser single “Secret”), Madonna dangled her Truth to the world, breaking down long held presumptions about the “appropriate” boundaries between pop stars and fans. But it was the kind of spectacularly orchestrated performance of disclosure that created more cover for an artist whose art of self-invention has long been lauded.

The sisters who paved the way for her in this regard — funk rebel Betty Davis and genre-busting icon Grace Jones — are rarely given their due for the shape-shifting, boundary-crossing pop world that they helped to create. But each of these black female singers — these self-proclaimed outsiders — has finally received the documentary treatment this year in films that seek to pay homage to their insurgent eccentricity.

¤

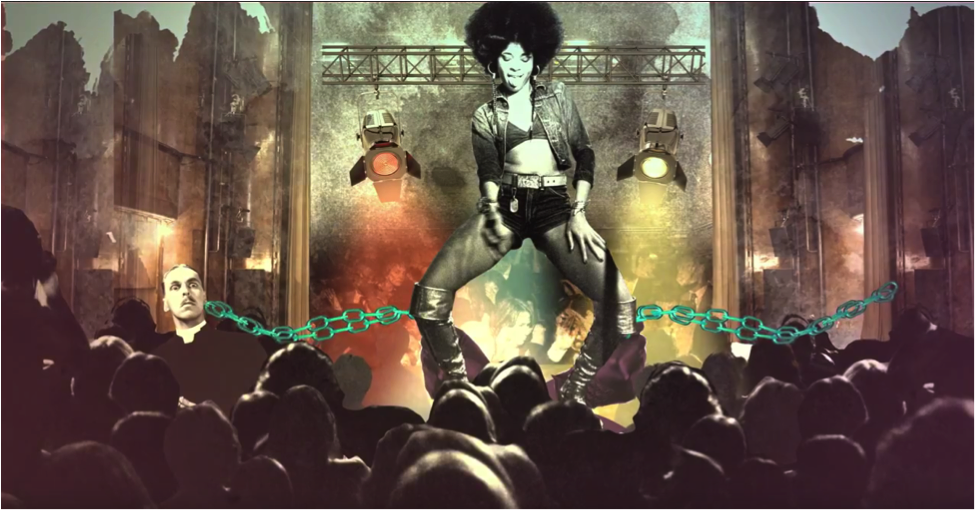

Betty: They Say I’m Different (2017, dir. Philip Cox) takes its title from Davis’s second album, released in 1974. The film traces the brief career of Betty Davis (née Mabry), a songwriter and model, former wife of jazz architect and luminary Miles Davis, unbridled vocalist and ferocious sonic experimentalist who released three sexually potent funk manifesto LPs in the ’70s before abruptly retiring from music and retreating from the public eye in a shroud of mystery. Riding the zeitgeist generated by Black Power and feminist liberation movements from that era, Davis sang would-be anthems about “not being like other girls” and mined “the nasty” and “the dirty.” Hers were articulations of sexual desire and forthright erotic agency that marked the end of Civil Rights assimilatory entertainment from the previous decade that drew on Supremes-like glamour and grace as weapons of reform. Davis’s repertoire innovated a kind of stank that others — from soulster Millie “blue-material” Jackson to neo-soul vamp Joi to hip-hop’s profane queens like Lil’ Kim and Nicki “Barbz” Minaj — have spun into pop chart gold. What set Davis apart from the pussy riot that rose up in her wake was her deep immersion in a musical counterculture populated by Bay Area musicians like Greg Errico of Sly and the Family Stone (who produced her debut album in 1973) and the multicultural members of Santana and Janis Joplin’s backing bands who respected the sanctity of heavy grooves, far-out rhythms, and expansive jam sessions.

This was music that merged the bohemian psychedelic vision of her friend (and possible lover) Jimi Hendrix with thick-as-gravy Larry Graham bass lines, all in the service of the sounds of black female pleasure and wanting. Davis’s “anti-love songs” rejected the gender-prescribed conventions of romance in favor of tough, frank observations about sex, power, and the exigencies of claiming one’s own carnal authority in life. With a rasp of a voice — part Tina Turner, part Bettye LaVette (both brash contemporaries of hers) — that often belied her ability to deliver James Brown–ish squeals and screeches, Betty Davis was a black female musician who refused the racial and gender caricatures projected onto her by reappropriating them and turning them inside out.

The brilliance of her game involved revolutionizing raunch, declaring the ambition driving her proclivities (on tracks like “Game Is My Middle Name”), and pushing back hard against foes who sought to keep her under their thumbs. “You dragged my name in the mud all over town […] I ain’t nothin’ but a nasty gal now…” she sings out on the title track to her 1975 final studio album, Nasty Gal. Her genius lay, in part, in her confrontational posturing, her commitment to undoing the constrictions of what black feminist critic Nicole Fleetwood famously refers to as “excess flesh,” the perilous representational condition of hypervisibility that black women have had to navigate through the ages. Davis chose to make her sexuality strangely and disruptively available to her audiences, all the while manipulating the terms of her exposure. And black feminist scholars from Maureen Mahon to Jalylah Burrell, as well as a long line of swooning grad students, have faithfully picked up in recent years on the signal and the noise that Davis was boldly selling back in the day.

With Betty: They Say I’m Different, Cox (also British) is intent on honoring the beauty of the artist’s enigmatic aura and elusiveness, while also pursuing the larger conundrums surrounding Davis’s retreat from the public eye. In this sense, the film walks a fine line between upholding the conventions of “lost and found” documentary explorations of forgotten or underappreciated artists (e.g., Looking for Sugarman, Standing in the Shadows of Motown, 20 Feet from Stardom) and rejecting the driving conceit of such films, which often hinge on a recuperative, triumphalist return to the limelight. Cox’s work suggests that nothing could be further from Davis’s mind, and he allows for the nuances of her ambivalent relationship to fame, notoriety, and the music business to manifest themselves at the level of form and content throughout the story that he’s telling.

The familiar talking head format (featuring Errico and pop critic Oliver Wang, an early champion of the now-vibrant revival of and critical passion for her work) quickly gives way to something poetically offbeat and intriguing. Davis doesn’t appear squarely on camera but instead materializes in suggestive shots as a silhouette, in fragmented form (a hand here, an eye there) or as a distant figure sitting in solitude. This decision destabilizes the biographical arc of the film. What could have been a straight-ahead tell-all is instead a haunting mood study with an array of figures — fans, former bandmates, family, scholars (of which black feminists are, it’s worth pointing out, conspicuously absent), and legacy musicians — who share screen time with a familiar, husky voice making sage, pointed observations about her life, career, and the pop world hustle: “The music business — it’s not all glamorous…”

Cox acknowledges the absence of a fully visible Davis with shots of empty rooms and well-manicured hands (bejeweled and sporting on fleek pastel blue polish) writing in a notebook, pressing a tape recorder. To these are added out-of-focus, profile, and shot-from-behind images of a graying woman sitting alone in a parlor, dressed in a fly white suit, lighting incense, settled in her solitude. For the most part, this technique works, cultivating a kind of wise yet ethereal Davis presence that hovers throughout the film. Most importantly, Cox gives Davis room to characterize her own sound (“I’d just say it was raw”) and to acknowledge that “I know many people tried to find me, wanted to ask me questions […] Now I’m old, but I feel I’ve reached the top of the mountain, and from there I can see clearly the path I’ve taken.”

Davis spins her own hypnotic mythology as she invokes the figure of a black crow as a kind of Hurstonian folk avatar, the artistic force that lives inside of her, that brings her “Howlin’ Wolf, Jimi, Miles” and other black sounds “in a whirlwind” and marks her from “the beginning of being different.” This is a film that draws on numerous representational and narrative resources to convey the art of Davis’s difference — from the colorful animation collages that stand in for the scarcity of visual performance footage, to the moving testimonials of relatives and girlfriend confidantes. To his credit, Cox seems most interested in offering a balance between the solitary Davis who rarely gives interviews and the range of individuals who loved and still admire her — from Pittsburgh sisters who marveled over the guts and glory of her ribald act to the members of her band who long to play with her again and, in the film’s most touching moment, gather together in a bid to reach out to her by phone.

Betty: They Say I’m Different keeps its eye on the ball, paying close attention to Davis’s aesthetic evolution, drawing out her memories of her grandma introducing her to classic women’s blues and relying on the always sharp commentary of black music critic pioneer Greg Tate to flesh out her influence on the abusive Miles, his sound as well as his look, during their turbulent one-year marriage. Trauma lingers in this story — especially as it relates to the death of her father — but it is not where this tale ultimately ends. Rather, we get the voice of Davis, artfully withholding pieces of herself and alluding to the perils of claiming the non-normative as a badge of honor. She holds steadfast to her principles of being distant and different as a lifeline and a lesson to all her freaky acolytes out there. She is both on guard and profoundly philosophical, offering us finally an alternative way to contemplate black women’s musicianship without trafficking in tragedy or unveiling privacy.

¤

Nobody threads the needle of nakedness and secrecy more brilliantly than Davis’s high-profile peer Grace Jones. Having reveled in the international spotlight for more than four decades as a vocalist, performer, and model provocateur, the Jamaican superstar has spent a lifetime commanding the attention of the masses while posing in everything from elaborate prêt-à-porter costumes to barely there dancewear. Jones, the godmother of queer utopic disco and Afropunk, has proven her cultural stamina, tirelessly continuing to tour, hitting the talk show circuit, and releasing 2015’s deft and absorbing page-turner I’ll Never Write My Memoirs, her tell-all that she penned with Paul Morley. That juicy give-’em-what-they-want tome doesn’t skimp on gossip (taking a bad trip courtesy of Keith Richards, affectionately telling Tina Turner that her stage charisma made her want to sleep with her), but it also provides Jones, who turned 70 this year, the chance to showcase her captivating intellect — the depths of her knowledge and trenchant insight about colonialism in the Caribbean, non-binary gender and sexual formations, and the radical spirit of the queer sounds and looks that she pioneered in the 1970s and ’80s.

I’ll Never Write My Memoirs is perhaps the most cogent and enthralling musician’s narrative about disco as it seamlessly weaves together Jones’s immigrant reflections on social alienation and the politics of belonging (“Black but European. European, but Jamaican. It was something I would always have, a mixture of places and accents that I added to as I moved around, constantly relocating myself physically and mentally”) and the fluidity of her identity (“I was black, but not black; woman, but not woman; American, but Jamaican; African, but science fiction”). She describes the music that would encapsulate the post-Stonewall jouissance of queer life alongside the work of her collaborators deejay Tom Moulton, photographer Richard Bernstein, and fashion designer inspiration Issey Miyake. This was music that, as she puts it, “choreographed danger” and pulsated as a “sweaty symbol of transition.” Jones classics such as the wickedly salacious “Pull Up to the Bumper” and “Warm Leatherette” transduce that universe into the extended execution of vinyl foreplay. This was avant-garde eroticism that matched Davis’s growl, set to a sinuous, prowling beat.

Sophie Fiennes’s mesmerizing and slightly impenetrable Grace Jones: Bloodlight and Bami (2017) captures the rush of Jones’s worlds in a pop star documentary that defies categorization and steers entirely clear of familiar markers of the genre. There are no director’s interviews with the artist, her backing band, lovers, or critics. Fiennes, whose previous works include films produced in partnership with trickster philosopher Slavoj Žižek, removes this structure in order to transport audiences to the dizzying and unpredictable time and space of an entertainer whose life and work encompass the perpetual transgression of borders. From its opening moments onstage with Jones, the film parachutes audiences into the immersive realm of its star: on stage, off stage, backstage, in the studio, around the kitchen table with family in Jamaica, up in the church pews, alone in the backseat of Eurocabs, and beyond.

“Bloodlight” refers to the red light in the studio that signals go-time, the time of concerted art-making, the realm of being “on” and in the zone of performance. “Bami” is the everyday flatbread in Jamaica, vernacular nourishment that is the ubiquitous stuff of life in Jones’s island upbringing. Fiennes’s film remains faithful throughout to exploring these twinned ideals that shape this remarkable entertainer. Bloodlight and Bami also lets audiences know from the get-go that this is a Jones endeavor (and, indeed, the credits list “Beverly Jones” — the entertainer’s birthname — as one of the film’s producers). Early on when answering an adoring fan’s query as to whether or not she’d do another movie, the towering diva resolutely declares: “My own.”

So what does a Grace Jones film look and feel like? It takes its cues from the stage, of course, with riveting concert footage that reminds the world of just how dazzling and audacious a performer she continues to be, even as she turns now toward her eighth decade on this earth. Rather than relying on archival clips, all of the major stage performances are fresh appearances that Fiennes shot with cinematographer Remko Schnorr on Super 16 mm film during recent tours. It’s these scenes that anchor the narrative, which begins and ends in Jamaica. Jones comes to us immediately in Bloodlight and Bami’s opening scenes holding a gold, tribal mask in front of her face, with flowing blue garments flapping in the breeze, swathed in darkness. That halting contralto sings out to us the familiar opening lines of her sensuous ’80s dance anthem “Slave to Rhythm,” and we are off and running — moving in the life and according to the beat of Grace.

“My mother’s waiting for me!” Jones tells her stage door admirers. Fiennes allows seemingly casual footage like this moment, which transitions the film to Jones’s homeland, or the artist’s always pithy stage patter to subtly flag scene changes in lieu of more declarative narration. Such choices might feel disorienting and hard to follow for those not familiar with Jones’s life and career or who are impatient for a forthcoming tale of her celebrity. If you aren’t, for instance, aware of the lasting impact of step-grandfather Mas P’s brutal reign in the family (which she discusses at length in her memoir), and the ways in which Jones and her siblings have processed his tempestuous hold on the family, then the suppertime discussions about him might fly over your head. What’s undeniable and revelatory to any viewer, though, is the way that Jones translated such traumas as well as the many pleasures of her own fiercely self-curated existence into breathtaking performances of the rebelliously fabulous and the sumptuously odd.

Like Davis, Jones too has been experiencing something of a long-overdue renaissance in academic studies, where scholars such as Francesca Royster, Kara Keeling, Ricardo Montez, and Uri McMillan have been mining her work for its postmodern articulations of race, gender, and sexuality. Bloodlight and Bami conveys not only the non-stop fluidity of Jones’s performances on and off the stage but also the consistent focus and fastidious labor that this legend puts into her artistry — whether in the studio with longtime producers Sly and Robbie or in the green room following an ill-conceived performance on French television.

For the past decade, Jones has increasingly used her work to examine her life’s journey from Jamaica to the cold nether regions of Syracuse, New York (where she moved with her family as a teenager), to the center of the nightclubbing galaxy. Her magnificent 10th studio album, 2008’s Hurricane, features one of her very best singles ever, the piercing and contemplative “Williams’ Blood,” which marked Jones’s return to the studio after a 19-year hiatus and introduced to the world a musician who was newly invested in interpolating the autobiographical into her art. “You can’t save a wretch like me,” taunts Jones, “I’ve got the Williams’ blood in me!” Such a song lays bare the history of her family tree and her deep identification with “black sheep” maternal grandpa Dan Williams, who fled the growing religiosity of the family in favor of greener pastures as a traveling pop musician. Co-penned with Prince Revolution alums, the brilliant songwriting team of Wendy Melvoin and Lisa Coleman, “Williams’ Blood” is Jones’s tour de force, an apotheosis of self-creation in the face of disciplinary forces (“Why don’t you be a Jones like your Sister and your brother Noel?”).

In her show-stopping renditions of this track, Jones has been known to rock signature crowns, mile-high hats, and voluminous coverings, which sometimes entirely obscure her stunning visage or draw the eye to the trappings of her artifice. Bloodlight and Bami doesn’t disappoint in this regard. With a highly structured headpiece that resembles a warped nun’s habit, she testifies in song to her can’t-be-tamed misfit past, capping off her performance with her subversive cover of “Amazing Grace” and saving herself right before our very eyes. The miraculous contrasts bound up in her varied readings of her “blood” speak to the ethos of Jones that this film faithfully pursues: reveal to create even more mystique.

Her ever-changing act is an exquisite execution of what philosopher Fred Moten has called “the right to obscurity,” which, he argues,

corresponds to the need for the fugitive, the immigrant and the new (and newly constrained) citizen to hold something in reserve, to keep a secret. The history of Afro-diasporic art, especially music, is, it seems to me, the history of the keeping of this secret even in the midst of its intensely public and highly commodified dissemination.

Like our Betty’s avowed difference, Jones’s marvelously strategic obscurity is both weapon and protection, a primer for the freaks, the outcasts, and the dispossessed on how to stay fleet of foot, how to evade capture.

The fugitive flow between spaces and Graces in this film mirrors and complements this vision and offers viewers a multifaceted take on her management style, her performance preparation, the details of her sweat and vigor belting out bangers (“Nipple to the Bottle,” “Love Is the Drug”), fighting for studio time with her collaborators, applying makeup, and slipping into garments — the repertoire of her masquerade. These sorts of show-biz odysseys dialectally flow back and forth between intimate family gatherings; a photo shoot with infamous one-time lover, collaborator, and father of her child, Jean-Paul Goude (which includes a blink-or-you’ll-miss-it reference to the pathbreaking, primitivist-meets-vanguard images that she and Goude produced together in the ’80s); her travels around the island with son Paulo and niece Chantal; and a memorable trip to the family’s church, a nod to the artist’s surprising Pentecostal roots that sowed the seeds of her youthful rebellion. The effect of this back-and-forth creates a kind of spellbinding ambience and is perhaps one of the most innovative ways of respecting and reflecting Jones’s trademark opacities as an entertainer.

You have to be willing to go with the rhythm of this film in order to grasp and her magnetism and mystery, which, it should be noted, remain intact from that first glimpse of her masked all the way to the closing moments on a Jamaican mountaintop with relatives, surveying the land against the backdrop of the warm orange dusk. We hear a patriarch’s voiceover remark that “I’ve been paying taxes on this land for the past 25 years […] and my daughter’s going to do something with it.”

As the credits roll, the stage empress gets in formation, accruing colossal energy with a prodigious headdress, black leotard, and billowing capes whipping in the wind. We see her serenading this site of maroonage that is her homeland and simultaneously delivering a stentorian message to the world with her ominous reading of “Hurricane”: “See me here I come … I am woman / I am sun … can’t see where I run / No matter how far! … I’ll be a hurricane / Ripping up trees!” At the end of it all, beware and take cover. Someone’s got a secret, and she’s not telling.

¤

Daphne A. Brooks is professor of African American Studies, Theater Studies, and American Studies at Yale University.

LARB Contributor

Daphne A. Brooks is professor of African American Studies, Theater Studies, and American Studies at Yale University where she teaches courses on black literature and culture, performance studies, sound studies, and black feminist theory. She is the author of Bodies in Dissent: Spectacular Performances of Race and Freedom, 1850–1910 (Duke UP, 2006) and Jeff Buckley’s Grace (Continuum, 2005), and the forthcoming Subterranean Blues: Black Women Sound Modernity (Harvard UP).

LARB Staff Recommendations

Journey of Miles

Clifford Thompson charts the heroic American journey of Miles Davis.

Beyond "Kind of Blue"

Why Miles Davis is more than his best-known recording

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2018%2F07%2FBrooksJones.png)