Lives Derailed, Novel Unfinished

By David FrancisJuly 27, 2013

The Hanging Garden by Patrick White

READING THE UNFINISHED MANUSCRIPT of an iconic dead novelist, especially one you admire, feels prurient, especially when you learn that the book in your hands was published contrary to the author’s wishes. It’s like sneaking a look at an elderly friend emerging from the shower.

From 1935 until his death in 1990, Patrick White published 12 novels, three short-story collections, and eight plays. When awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1973, he became Australia’s first and only winner of that coveted coin. Still, the most revered figure in modern Australian literature is largely unknown to Americans, though his titles may have a familiar ring — among them are Voss, Riders in the Chariot, The Twyborn Affair, and The Solid Mandala.

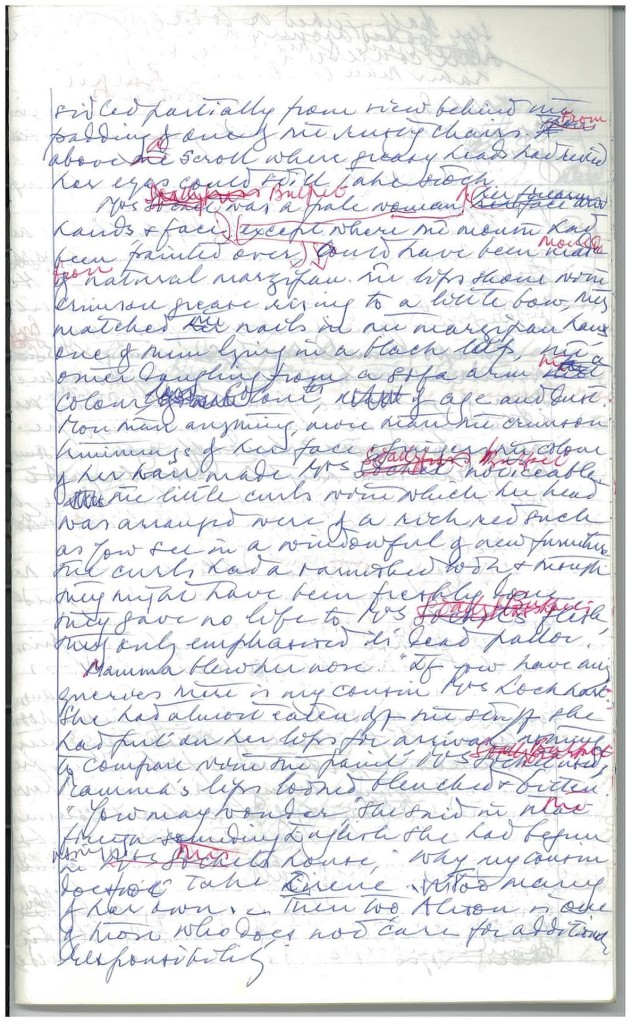

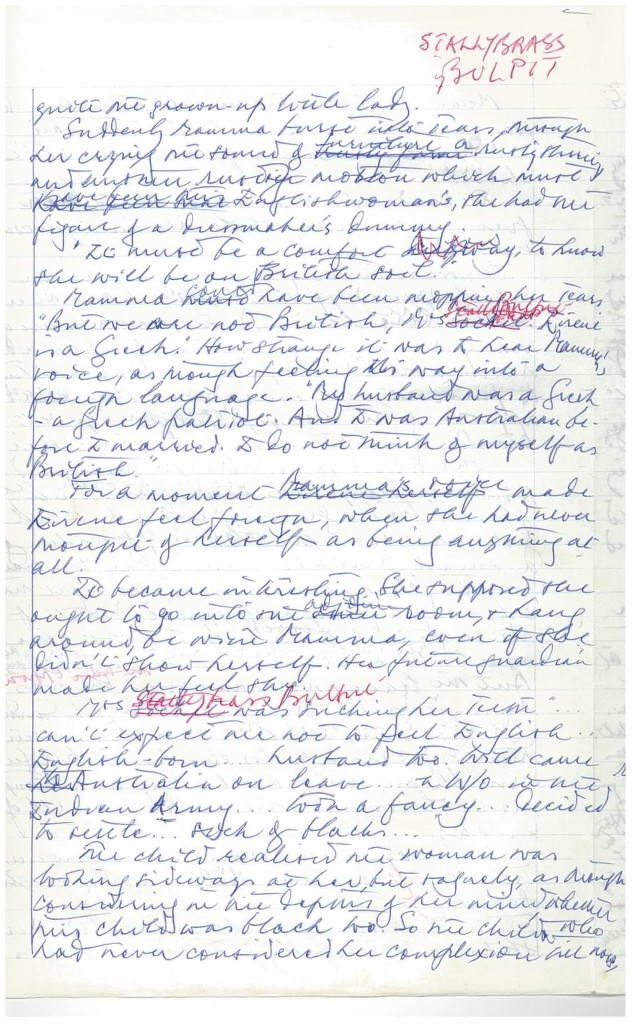

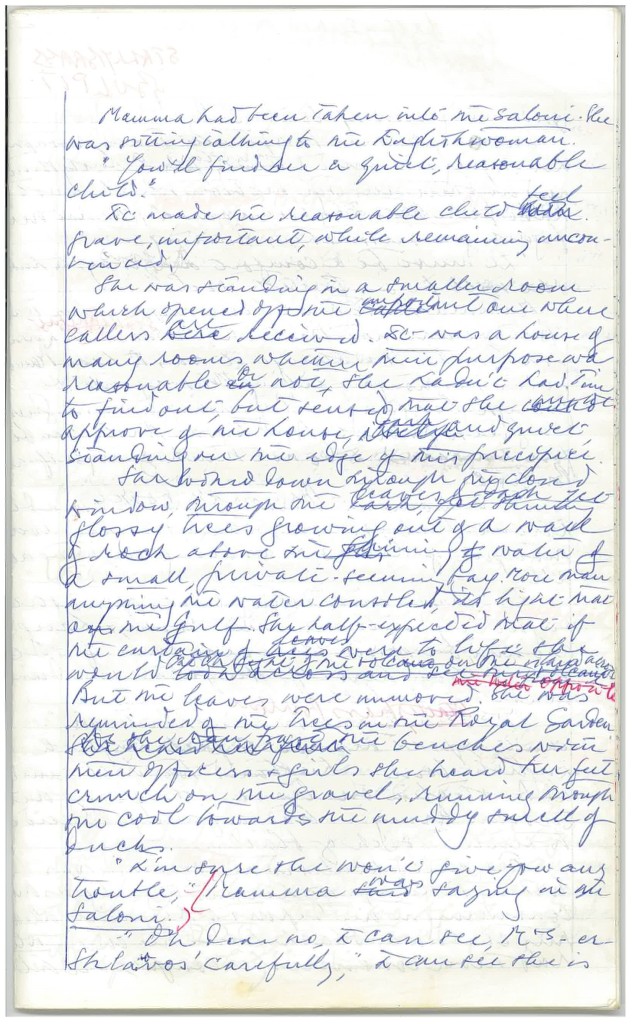

On White’s death, a manuscript on quires of foolscap was found shoved in his desk drawer, written in his usual elegant but not easily decipherable long-hand — blue ink marked up in red. The completion of this abandoned 13th novel, the first of a proposed triptych, had been deferred by White’s old age and failing health, not to mention his involvement in Australian politics (a failed effort to ditch the Queen), and a theatrical collaboration with Jim Sharman (of Rocky Horror Picture Show fame).

After White died, the pages were stowed on a shelf by Barbara Mobbs, his long-time friend, agent, literary executor, and the transcriber of all his handwritten manuscripts. It wasn’t until 16 years later, and after the death of Manoly Lascaris (White’s partner of almost 50 years), that White’s remaining papers, including the manuscript, were released and sold to the National Library in Canberra. Despite White’s wish that none of his work be posthumously published, Mobbs finally acquiesced and allowed a verbatim transcription of The Hanging Garden to proceed for publication in 2012, to mark the 100th anniversary of White’s birth.

Speaking with Barbara Mobbs at the recent Sydney Writers’ Festival, I learned that, prior to his death, White lit various fires and burned numerous published and unfinished writings. According to her, if he’d truly wanted this manuscript destroyed, he’d have taken it out of his desk and done it himself. He’d often shown it to her, but “he never told me to get the matches.” Perhaps, consciously or not, White knew that The Hanging Garden was too verdant and promising to disappear from the world unheralded. In honor of his anniversary, and as a literary treat for both his devotees and new readers, it deserves some trumpeting now.

The novel opens in 1942, on the cusp of the Second World War. Eirene Sklavos, a young expatriate from Greece, is delivered by her mother to a tumble-down house in Neutral Bay (a Sydney suburb) to shield her from the war in Europe. The house has a lush, neglected garden that overlooks the water, and is owned by a curious woman called Mrs. Bulpit whom Eirene observes in excoriating detail:

[A] pale woman, except where the mouth had been painted over. Her forearms, hands, and face could have been moulded from natural marzipan. The lips shone with crimson grease rising to a little bow, they matched the nails in the marzipan hands, one of them lying in a black lap, the other dangling from a sofa arm the colour of age and dust. More than anything, more than the crimson trimmings of her face and fingers, the colour of her hair made Mrs. Bulpit noticeable, the little curls with which her head was arranged were of a rich red such as you see in a windowful of new furniture. The curls had a varnished look and though they might have been freshly done they gave no life to Mrs. Bulpit’s flesh, they only emphasised its dead pallor.

White’s artistry in narrative, language, and description is all over these early pages.

For Eirene, a girl whose father, a Communist sympathizer, had been shot in an Athens prison, and whose mother has just abandoned her in the Antipodes, “the future was a shapeless dread in what was a stockstill present.” Still, she finds some comfort. She learns that a boy has been billeted in the same house. His name is Gilbert Horsfall, and he has escaped the London Blitz that killed his mother.

He had spent most of the afternoon pitching stones into the water. The glare no longer made him squint. Salt scales had replaced the scurf of his own skin on legs and arms, now the colour of Arnott’s Milk Arrowroot. (“Most Australian kiddies love these biscuits, and I expect you will too Gilbert.” He agreed they were — beaut, carefully.) He licked the scales off his left forearm before pitching his last stone. As afternoon faded, long brassy fingers of light extended from the direction of the city. They reached out at him, but fell short, distorted by ripples in mauve-green water inserting themselves in cracks of the gull-scribbled sea wall. A gull on the long slow curve of its flight let fall a squeeze of white almost like toothpaste on the pale hair. By now so dazed by sun, air, dreaming, he barely bothered […] He had heard a car arriving at the house above. Car doors. Too far for voices to carry. But he shivered for the sound of the foreign voice he hadn’t heard.

In the succulent, vine-woven garden, Gil and Eirene fashion a tree house, their sanctum away from the prying eyes of Mrs. Bulpit. Scenes unfold in their “cubby” that are as sensual as they are unvarnished, the points of view so intimate that you can’t help but touch and be touched by them.

As these two derailed lives coalesce in a sultry and halting awkwardness, White’s sensitivities to the vagaries of displacement, as seen through the lens of Eirene’s “Greekness”, is ever-present, and his descriptions of the brink of adolescence are as dreamy and fertile as the garden in which the story unfolds:

The moon’s blue, gelatinous face with the forms of those milky twins inside it […] Before falling asleep, before the act of levitation took place, they drifted together again, their unprotesting skins, inside the steamy envelope of Bulpit sheets.

White spent his early years at private schools in New South Wales until, at the age of 13, and very much against his will, he was launched to Cheltenham College in England. He went on to study modern languages at Cambridge and, intent on forging a career as a writer, spent some time in the United States before settling in London. His career plans, like everyone else’s, were interrupted by World War II; the British Royal Air Force posted him in the Middle East and Greece. His wartime experiences were transformative — the Western Desert created in him a nostalgia for the harsh, dry landscapes of Australia. While in Alexandria, he met Manoly Lascaris, the son of an American woman and her wealthy Greek-Egyptian husband, and the men became lovers. After the war they returned together to Australia where they lived together until White’s death (Lascaris died in 2003).

The Hanging Garden is infused with White’s deep knowledge of war and dislocation, his own internal divides and conflicting loyalties to Europe and Australia, and, no less crucially, the varying moods of his own childhood garden. The novel feels like both a departure and a return for White, as it tenderly sifts through the fortunes of two children of war who are thrust together and then just as suddenly torn apart:

Eirene’s aunt started off. “You can’t expect only happiness, dear, out of life,” as if you didn’t know, “the blows will come as well.” […] Go on tell, I can take it, because you have good as told me […] tell this aunt you are half moth who knows by downy instinct.

The novel does not aspire to the ambitious, labyrinthine scope of much of White’s earlier work, including Voss (1957), perhaps his best-known book, which was also turned into an opera. Marinated in the spirituality of Australia’s indigenous peoples, Voss tells of an epic, ill-fated exploration into the country’s foreboding outback, and of a secret, psychological passion between the explorer Voss and the young orphan Laura. The Twyborn Affair (White's last major novel, published in 1979) is also both knotty and sweeping: it follows the fortunes of soldier Eddie Twyborn, reborn first as the mistress of an aging Greek tyrant in the south of France, and then re-emerging as the madam of a high-class London brothel during World War II.

The Hanging Garden is more intimate, less daring and formidable: it explores a narrow world through the acute susceptibilities of these two young “reffos” (Australian slang for refugees). Their interior worlds are laid out lovingly in a mix of mostly third-, but also first- and second-person narratives, with an unexpected burst of voice from Eirene’s aunt, Mrs. Lockhart who has skin “rough as bark, scaly as a hen’s legs,” and who tears around Sydney in a noisy rust bucket that she imagines is a lustrous, winged Bentley for “delivering children to school, bullying greengrocers and butchers into letting me have their wartime produce cheap.” The Lockhart, as Eirene dubs her, lives nearby the Bulpit house, but she has too many boy-children to risk taking on Eirene — and, we later learn, a husband who proves, at best, dicey around young girls.

While the changes in point-of-view and person are not always seamless, and though the first half of the novel resonates more profoundly than the second, for me, as a writer, the book is exhilarating. I was humbled to realize how the pitch of this untrammeled work rings so purely on the page. And, while written 30 years ago, it still feels uncannily fresh and gratifying.

As a boy in Australia, my first exposure to White was his early tripartite novel, The Aunt’s Story, published in 1948, which along with Tess of the D’Urbervilles, was a required text at school. As a 12-year-old, I had little time for Tess traipsing endlessly through the swedes, nor was I particularly keen on the world of White’s traveling aunt, which I regarded as an unmitigated slog. It wasn’t until re-reading the novel in college that I appreciated White’s flourishes of language and his deft exploration of the interior world of Theodora Goodman, the plain maiden aunt who begins her descent into madness in the exotic garden of a bleak French hotel.

The Hanging Garden is stamped with White’s emblematic skill at guiding his readers close along the veins, and into the psyches of his characters. The departure here is the subjects of his interior explorations, of how these two children of war make sense of their strained and strange environs, and how they brush uneasily against the sensations of their unguided adolescence. White inhabits the awkward rhythms of childhood with a sympathetic and unflinching focus.

That said, in its bare, uncompleted form, we have little sense of what White had planned for the narrative arc, other than a note scrawled at the end of the first part of the manuscript: “14 in 1945, 50 in 1981,” suggesting that Eirene was to live into the present day of 1981, the year White was crafting her story.

Delving into an unfinished novel is a sticky business. The chance to sneak behind the fluffed and combed prose and cast a glance at the bare scaffolding can be fraught with expectations and the seeds of disappointment. To peel away the layers of craft of another writer feels inherently furtive, like rummaging through an author’s diary with a false impunity.

Devotees of Nabokov who read his fragmentary The Origins of Laura often feel frustrated or even cheated. Nabokov’s son and literary executor, against his father’s wishes, undertook its transcription from 138 handwritten index cards (comprising what were to be the first five chapters, some from just a couple of cards, along with notes and random sentences, complete with grammatical and spelling errors). These were arranged in sensible, if debatable, order, and published with facsimiles of the index cards in a form that could be detached from the book and reordered, as a kind of puzzle.

While the publication of The Origins of Laura may have been a worthy exercise, and perhaps in the best interests of literature at large, the end result is neither fluid nor inspiring, and has often (perhaps inevitably) been regarded as lacking the brilliance and polish that marked Nabokov’s completed works. This of course raises the question: to whom does a writer’s work belong — to himself or to his public? From the grave, Nabokov would likely look back and still shout No! to The Origins of Laura, while White might smile at what has been done with his pages. On the other hand, White is reputed to have been cantankerous and oppositional at the best of times, so it’s doubly hard to know. He might well wish he’d taken a match to the manuscript after all.

Regardless, admirers of White are fortunate here — perhaps because he was both further along in the work than was Nabokov, and because his pages are less episodic and more cohesive. The Hanging Garden, also transcribed verbatim, gives us prose that lies easily and cleanly on the printed pages, as far as those pages go. While a comparison with Nabokov is probably unfair, White’s language feels freer and more naturally honed. And, as with the perforated copies of Nabokov’s cards, White’s handwritten pages (an example of which has been included here) is fascinating. They demonstrate the way White wrote, rhythmically and lyrically right out the gate, sparingly self-edited in red ink.

This slim and masterful finale to Patrick White’s epic literary gift is not only a testament to his skill — the way the sentences emerge onto the page so startlingly refined — but also to the purity and clarity of his vision: the work genuinely verges on standing alone unto itself, unfinished but still fulfilling. It does more than hang together; it is worthy and lovely in the fashion in which it was left. How often do we get to see a Nobel laureate emerging naked, and delight in what we see? I just hope Mr. White would be as pleased.

David Marr — White’s biographer, who wrote the Afterword to The Hanging Garden — describes it as “a masterpiece in the making,” and characterizes the abandonment of the novel after 50,000 words as “a watershed in White’s life and a loss, a damn shame, for Australian writing.” Yet I, for one, am grateful that those 50,000 words have been laid out for us, unadorned, like a bowl of almost-ripe cherries. While it was likely tempting for editors to cover White’s pages with their own red ink, the Venus de Milo does just fine as it was found, without prosthetic arms, and Shubert’s Unfinished Symphony is pretty splendid as is.

¤

LARB Contributor

David Francis’s first novel Agapanthus Tango was published in the US as The Great Inland Sea. His second novel, Stray Dog Winter, was the Australian Literature Review’s Novel of the Year, and won the 2010 American Library Association Stonewall Prize for Literature. For more information, go to www.straydogwinter.com.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Updating "What Maisie Knew"

On the film adaptation of Henry James's late-Victorian novel

My Bolaño Archive

1. THE FIRST PUBLIC EXHIBITION of the papers and personal effects of the Chilean author Roberto Bolaño is the Centre de Cultura Contempor&agrav...

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!