"Piety and Perversity: The Palms of Los Angeles" is part of a collaborative series the Los Angeles Review of Books curated with Flaunt magazine for its 15th anniversary issue ("The Selfie Issue"). The series — focusing on the cultural iconography of the palm tree — includes contributions by Todd Edwards, Ava Marie DuVernay, Michael Jaime-Becerra, Lynell George, David Ulin, Nina Revoyr, Derek Boshier, Maria Bustillos, and Victoria Dailey. This is the first editorial collaboration between the two magazines. Click here to read the rest in the series.

¤

PARISIANS CLAIM THAT IN PARIS, one is never more than 400 yards away from a Metro station. In Los Angeles, I am equally certain that one is always within 400 yards of a palm tree. Scores of streets are lined with them; they are ubiquitous in domestic and public gardens; they rise from hilltops; they tower above cemeteries; they front museums, movie studios, hotels, hospitals, municipal buildings, modest apartments, and lavish villas; they are clustered around swimming pools; they dominate the skyline — they are everywhere, and have never been more popular. The city’s 200-year love affair with palms has never ceased, and rather than waning, the affair is waxing. From the first palms planted by Spanish padres to the city of Beverly Hills, which recently, in an act of cosmetic alteration, created a palm-lined, palm-bisected thoroughfare on upscale Rodeo Drive, the palm has been the tree of choice for Angelenos.

Other regions boast of their trees — the South’s magnolias are legendary, while the Southwest raves about its mighty ponderosa and piñon pines. New England is justly proud of its elms and maples. California has the monumental sequoias. Cities are not usually identified by trees, yet Los Angeles, whose native trees include sycamores, oaks, cottonwoods, and willows, is, curiously, not recognized for any of them. Instead, desert-dwelling palms (and, later, tropical varieties) have become a visual synonym for Los Angeles, resulting in a profound horticultural myth that has produced unintended, detrimental consequences.

Lately, as I have been scanning the local horizon, the pervasive palms have begun to make me feel queasy. In fact, they now irritate me. I long to see a vista uninterrupted by the skinny, merciless palms — they mock the very idea of shade, and in a region with abundant sunshine, their presence is exasperating. Like alien invaders, reckless colonizers, and “escaped exotics,” as invasive plant species are known, palms have driven out more modest species, claiming, as autocrats do, the exclusive right to reign supreme — they alone signify the arboreal realm of Los Angeles despite their inability to provide shade, their over-reliance on water and their environmental incongruity.

It is time to retire the myth of the palms; they have become a cliché. I have begun to realize that Los Angeles has outgrown its palm-based myths and superannuated cultural assumptions. Angelenos! You no longer need to rely on the unsophisticated masquerade of the fronds. Let us investigate how the palm myths originated — and let us retire them with a regional narrative more in keeping with the way we think now. In Los Angeles, where appearances can often deceive, it is time to decode the message and mythology of the palms and acknowledge that we have outgrown their deceptive messages.

At this point, you may well ask: in a place based on myth — after all, the town is named for angels — what harm can there be in yet another one? I ask you to reconsider. This interloper into the welcoming environment of Los Angeles has come to dominate not only the streetscape, but, worse, the mythos. It is a case of identity theft that has been so complete that to question it sounds like heresy. Many of you might be aghast, angry even, that I have suggested a rethinking of the palm. Yet my small attempt at unraveling the myths may herald a new understanding of palmy Los Angeles and how it got that way — and provide a path to a future arboreal reality for the city. And if you think I am excessively anti-palm, I assure you I am not — I do not blame the palms, they have their place. Rather, I blame their kidnappers who, seizing them from their native habitats, intended that they represent fantasies, whether of piety, exoticism, pleasure, or promise. Poseurs all, the palms revoked and reviled the true natural environment of Los Angeles, a much more subtle one than the palms represent.

Of course, we must immediately acknowledge that the palm is not the only intruder in the treescape of Los Angeles. Because of its preternatural ability to sustain nearly all newcomers, the irrigated soil of Los Angeles has accommodated the growth of millions of immigrant trees, among them: orange, eucalyptus, pepper, and jacaranda. (Isn’t this also the true, positive message of Los Angeles, that like its welcoming soil, the city has embraced millions of immigrant settlers?) But it is not the accommodation that is the problem; it is the false pretenses under which the palms were planted, which we will examine shortly. Unlike palms, the other immigrant trees originated in similar environments and parallel climates, and they seem perfectly at home in their transplanted state. They were not intended to imply anything other than their beauty and practicality as trees. Importantly, such trees provide shade and diversity, as well as fruit and flowers of great usefulness and beauty. Before you refute this by saying that there are indeed date palms in Los Angeles, be aware that while they are here — typically the Canary Island date palm — they do not bear edible fruit. And actual date palms need the heat of the desert to produce succulent dates, which is why the date industry is centered in Indio. Pathetically, the mighty Medjool date trees (Phoenix dactylifera) recently planted on Rodeo Drive cannot bear fruit due not only to the lack of heat, but also to the impossibility of fertilization, which must be done by hand, much like thoroughbreds. So there they stand, kidnapped and castrated, examples of an incomplete dream. I pity these poor palms.

The palms of East Lake Park (now Lincoln Park) decorate this small souvenir china vase, circa 1900.

PALMS IN THE ADOBE AGE

When the city was young, during the Spanish and Mexican period, there were barely any trees in the little village; the majestic native oaks that dotted the landscape were especially prized. They became the subjects of early photographs of the region before the proliferation of the palms; in fact, nary a palm tree was in sight in the original landscape of Los Angeles. Later, when a few were scattered from downtown to San Fernando, relics of Los Angeles’s adobe age, the locals treated them as anomalies It was the padres of the Spanish missions who first imported palms to Southern California, planting them from seeds they brought with them from the Canary Islands and Mexico. Interpreting their newly conquered territory as a latter-day Holy Land, they used the fronds during Easter ceremonies, especially on Palm Sunday, when actual palms evoked the Bible story of Jesus’s entry into Jerusalem; they also burned the fronds for use on Ash Wednesday. Palm trees are also mentioned numerous times in the Bible, including: “The righteous man will flourish like the palm tree,” (Psalms 92:12) and “Then they came to Elim, where there were twelve springs and seventy palm trees, and they camped there near the water” (Exodus 15:27). Although this religious connection to palms is now lost, it was the original motivating factor that caused the missionaries to plant palms at most of California’s 21 missions, including San Fernando.

Above: Isaiah West Taber. A great live oak, east San Gabriel, California. Albumen photo, c. 1875. The large, native oak trees were especially prized by photographers for their picturesqueness before the palms dominated the landscape.

Below: Semi Tropic California, promotional brochure, c. 1895. The cover features not only the phrase that lured to many settlers to Los Angeles, but also the twin palms of the Mission San Fernando.

Henry Chapman Ford (1828-1894), one of Southern California’s first artists, published a series of etchings on the California missions in 1883 and recalled a visit to the Mission San Fernando: “In the middle of [the] orchard are standing large native [sic] palms (Washingtonia filifera) the tallest of which is about 55 feet in height, probably the highest palm in cultivation within the limits of the United States.” Another pair of palms also captured the attention of early Angelenos: a photo from 1895 bears the title “The Old Palms of San Pedro St.” This pair, local landmarks because of their height and uniqueness, also made their appearance on the cover of a Los Angeles magazine in 1888. Look closely, and you will notice each image features a well, indicating that the palms were growing near a necessity: a plentiful source of water. Contrary to popular belief, palms need abundant water; when they are found in their natural desert habitat, they are always growing at oases where they are either fed by a spring or a stream or along fault lines where water rises to the surface. Palms are signposts of water, not a lack of it. The interior of a palm tree, with its system of spongy water pipes, is unlike that of other trees, making palms more like grass than trees. A mature desert fan palm can weigh as much as three tons, with most of the weight in water, and some date palms can weigh in at 20,000 lbs; such palms need a constantly moist soil to thrive. The old palms of San Fernando and San Pedro Street survived with well water, and like all of their subsequent brethren, they originated with seeds from the Washingtonia filifera palms of the Colorado Desert.

Above: Pierce & McConnell. "The Old Palms of San Pedro St." Boudoir photograph, c. 1895. This pair of palms, growing by a well, was a local landmark.

Below: Rural Californian, Los Angeles, July, 1888. The same pair of San Pedro Street palms was used on the cover of a local magazine.

Found in abundance in the Coachella Valley near the aptly named Palm Springs, or in the Anza-Borrego Desert east of San Diego, Washingtonia filifera — known as the California Fan Palm — is California’s only native palm, and nearly all of them in Los Angeles can trace their origins to these desert palms; local nurserymen were selling Washingtonia filifera seeds for one dollar apiece in the 1890s. A similar palm, Washingtonia robusta, or Mexican Fan Palm, the other great colonizer of Los Angeles, was imported to the Southland from the deserts of Sonora and Baja California. The genus was named for George Washington by the German botanist Hermann Wendland in 1879 when he saw some specimens growing in a greenhouse in Ghent, Belgium, where they had been propagated from seeds brought from the Colorado Desert in 1876. He recognized them as a distinct genus and named them “in honor of the great American,” and perhaps to commemorate the recent American centennial.

VICTORIAN PALMS

Victorians were mad about palms, and it is to their invention, the greenhouse, that we owe much of our palm legacy. These large structures built of cast iron and glass allowed the exotic flora of the world to grow and be seen throughout Europe and America — entire greenhouses were devoted to them. Evoking exotic climes, far-off colonies, and intrepid explorers, palms were emblematic of Victorian aspirations, and their biblical associations stirred the pious Victorian soul. A palm house was built at Kew Gardens in the 1840s; a large palm conservatory was on view at the Vienna World Exhibition in 1873; a decade later Emperor Franz Joseph commissioned a huge palm house at the Schönbrunn Palace, still the largest in Europe. At the United States Botanic Garden, a palm house was built in 1870. These are but a few examples of the Victorian palm mania.

The craze for palms in Los Angeles began slowly, but once underway, when it became clear that LA could become one huge, open-air greenhouse, it barreled on, changing the landscape — and identity — of Los Angeles completely. The City of Angels became the perfect laboratory for the Victorian ideals of productivity, piety, and exotica, and it was here that palms began to represent all three. In the 1870s and 1880s, when the area’s fledgling cities were laid out, city planners at first selected many kinds of trees to line their new urban streets, choosing trees that provided shade from the glowing sun and that were aesthetically pleasing when viewed en masse. However, when they realized they could plant palms, Victorians went at it with gusto. They were also thrifty: cost-conscious city fathers often bought the cheapest trees they could find, resulting in some interesting choices. When Magnolia Avenue was laid out in Riverside in 1875, the plan was to line the street with Magnolia grandiflora, the showy, white flowers of which provide an intoxicating fragrance, but, at two dollars each, magnolias were much more expensive than the more common, and popular, eucalyptus and pepper trees, which could be had for just five cents apiece. To save money, the city decided to incorporate the cheaper trees and plant the magnolias at half-mile intervals along the road’s 10-mile stretch. Soon after, when some of the eucalyptus trees died, they were replaced with palms, the first time the palm tree was used on an urban thoroughfare. (Imagine the delight of palm-adoring citizens when they saw actual trees not in a greenhouse but growing along their avenues.) Despite the few-and-far-between magnolias, the road retained its name. Other cities would frequently copy Riverside and line their streets with palms. The palm craze was underway.

A view of the recently planted palms on Magnolia Avenue, Riverside, 1889, the first thoroughfare to be lined with palms.

By 1887, one writer wondered, “How will Angel City appear 25 years hence when those thousands of the princes of the vegetable world, the fast-growing mammoth palms, shall swing aloft their graceful ostrich plumes from every hill side?” (J. H. Von Keith, Von Keith’s Westward, 1887.) Von Keith’s nod to ostrich plumes was apt, as an ostrich farm had just opened in South Pasadena to supply the feathers for fashionable women’s hats; the feather fad subsided within a generation, unlike the permanent palm fancy. Within a quarter-century, palms had successfully colonized the landscape, and to answer Von Keith, by 1912, Los Angeles appeared as a palm oasis. It has continued to masquerade as such for another 100 years in a peculiar twist of horticultural history. Although native to the desert, the true identity of the palms was hidden, and the assumption grew that they were native to the entire region. Palms became projections of the changing narrative of Los Angeles, and while other trees went in and out of fashion, palms never did.

Just as the Spanish missionaries used palms to invoke Bible lore, Victorian Angelenos also enjoyed their religious connotations. In 1896, Los Angeles preacher Reverand N. T. Edwards delivered a sermon entitled “The Palm Tree as the Type of a Godly Man” in which he compared the palm tree, in its grandeur, to the divine pattern of God’s plan for mankind; because palms were a traditional symbol of victory, Edwards compared them to Christian virtue conquering sin (LAT, May 18, 1896). Palms were so popular that the University of Southern California, founded in 1880, claimed as its motto Palmam Qui Meruit Ferat (Let Whoever Earns the Palm Possess It). The motto was prescient, if not slightly reversed: the palm would come to possess Los Angeles.

Although the lure of the palms was potent, massive publicity was needed to induce new settlers and visitors to the Southland. Other ideals dear to Victorians were profit and growth, and regional boosters were eager to share the promise of health and wealth that Southern California provided while profiting nicely on real estate. Realizing that the region was located in the “semi-tropical zone” (i.e., the latitudes between 25° and 38° north or south of the equator; today, the term “subtropical” is used), promoters capitalized on the term, using it endlessly. Although it could have accurately described the Carolinas, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Florida, all of which fall in the semi-tropical zone, there was one major difference: Los Angeles is not humid. The city could provide the allure of the tropics without the humidity, and, as such, it became a tantalizing destination for millions, a false tropical paradise.

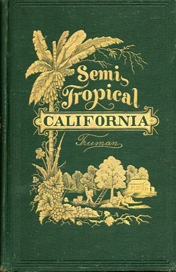

Above: The fantasy of the palms begins. The cover to Benjamin Truman’s Semi-Tropical California, 1874.

Below: Los Angeles and palms have become synonomous. The cover to a 1904 promotional booklet with Truman’s recollections of early Los Angeles.

Describing Los Angeles as “semi-tropical” was an act of genius and a promoter’s dream, especially after the Civil War, when Americans, battle-weary and often ill, needed a new arena in which to pursue happiness. With the joining of the rails in 1869, California was a mere train ride away, and the rush began, no longer for gold, but for sunshine and settlement. Several books were published that sold millions of copies, notably Semi-Tropical California by Benjamin C. Truman published in 1874; it took advantage of the dream, the desire — and the phrase. One of the first and most influential books to promote Southern California, it was responsible for thousands of readers making the trip west to see if Truman’s claims were true. They were. He provided accurate details about the newly developing cities, climate, water supply, agriculture, and the like. However, it was not the book’s contents but its cover that provided an imaginary idea of Southern California’s natural environment: a gigantic, fantastical quasi-palm, quasi-banana tree (laden with what appear to be coconuts) dominates the scene on the cover, its fronds perfectly framing the word “Semi-Tropical.” The myth is born: an image and a phrase entered the zeitgeist; one picture worth thousands of words. Thirty years later, when Truman recalled his early years in Los Angeles in yet another promotional booklet, its cover featured not a fanciful tree, but actual ones — four shaggy Washingtonia filifera. (Well, actually two trees — the photo had been cleverly altered into a mirror image of itself.) Palms had become the instantly recognizable symbol of the city.

Another writer, Charles Nordhoff, also influenced thousands of readers to head west when he published California for Health, Pleasure and Residence in 1872. Both Truman and Nordhoff were enlisted by the railroads to write promotional copy, and more than any single writer, it was the railroad companies that were the mightiest proponents of travel and settlement; they touted Southern California incessantly, selling not only rail tickets but real estate, selling home sites along their right-of-way all the while issuing thousands of brochures that championed the region’s many attractions. What is now the southern section of Glendale was originally the little town of Tropico, laid out in 1887 and named after the local Southern Pacific Railroad depot; it is no surprise that the railroad would name a station and a town “Tropico,” following the lead set by Truman and capitalizing on the reverie induced by the words “semi-tropical.” (The tropical dream never abated: the city of Hawaiian Gardens was founded in the 1920s as was the Cocoanut Grove, the celebrated nightclub at the Ambassador Hotel. In the 1950s and ’60s, newly built apartment buildings took such names as the Catalina Tropics, Glenlani Tiki, and Royal Palms.) Desert dreams conflated with the tropical longings, and palms were the proof.

By the turn of the century, the intense popularity of the palm tree was noticed by novelist Edward Wall, who stated in the Overland Monthly in 1904:

It is probable that nothing in Southern California attracts the attention of the tourist and sightseer more, or appeals more to his sense of the beautiful, than do the hundreds of fan-palm trees that are to be seen growing along almost every walk and drive and in nearly every garden, for nothing savors more of the tropical Orient than do these ever-green, thorn-ribbed trees whose hemp-fringed leaves shiver and quake at the least suggestion of a breeze, as though living in constant fear of Jack Frost, even here in California where “cold” has no place.

Where cold has no place. This was Los Angeles’s major selling point, and there was no better way to convey this than with pictures of palm trees. Early homeowners made sure to plant at least one palm in their gardens, proof that they were living in paradise. This idea became a birthright for Angelenos, who never wavered in their conviction that this land of palms was superior to all others. The imposing height of many palms — they can grow to over 100 feet — also gave bragging rights to Angelenos, whose history may have been short but whose trees were tall. They also grew quickly, as did the city. Wall also noted that the palms “savor of the tropical Orient,” suggesting an “anywhere but here” attitude in Los Angeles — as though the city could be made to look like any exotic, faraway place that would satisfy the wanderlust and travel yearnings of those unable or unwilling to explore foreign lands. This conjoining of the phrase “semi-tropic” with the image of palms had a profound effect on the region, causing Angelenos to think of their city as an ersatz tropical substitute, a veritable stage set, not quite the tropics but an improved simulacrum. Los Angeles’s protean ability, to become nearly anything other than what it is, has been its hallmark and destiny.

Yet not everyone was enthralled with palms; a few dissenters made their voices heard, without result. Novelist Grace Ellery Channing complained in 1899: “The shade trees are down — they ‘littered the streets.’ The ferny pepper is gone — its roots ‘humped up’ the superior asphalt […] Palms — as useful as telegraph poles for the purpose — serve as shade trees.” (The Land of Sunshine, July 1899) But these voices were few. And a new palm era was about to begin, neither biblical nor “semi-tropical,” but rather, sexy and possibly scandalous.

Above: A postcard from circa 1898 features a large palm and West Lake Park (now MacArthur Park).

Below: Stephen H. Willard. Along the Stream, in Palm Canyon, California. Color printed postcard, c. 1939. The palms in their natural desert habitat by a flowing stream.

Below: A Palm Lined Residential Street in California, Beverly Drive, Beverly Hills, California. Color printed postcard c. 1931. One of the well-known palm-lined streets in the area; the palms are still there, taller and trimmed.

THE PALMS OF HOLLYWOOD

Although the first palms in Los Angeles were those native to the dry desert, later, those from the wet tropics were planted. In an effort to appear as both desert and tropical, Los Angeles became a city of extremes, antithetical to any previous definition of urbanity. In so doing, it is known far and wide as a desert — with the cultural associations of bleakness and aridity to go with it — and as its opposite, a seaside tropical paradise with implicit themes of indolence and frivolity. But Los Angeles is neither: its climate is properly known as Mediterranean. Those imagining a tropical paradise where balmy breezes waft will find that the local winds are often the howling, sere Santa Ana’s — and the dream of a desert is dispelled when torrential downpours fresh off the Pacific flood the city in winter.

Yet the myths of the palms continued and expanded. Los Angeles was about to morph into Hollywood, the new center of world mythology and popular culture, where romantic fantasies, imaginative storytelling, and visual effects would stun the world. Los Angeles was no longer just an exotic horticultural anomaly based on an ersatz landscape of palm trees — it was about to emerge as the center of an infinity of imaginary landscapes. Los Angeles architect Sumner Spaulding remarked in the 1940s, “The wonderful part about Los Angeles is that you could tear down the whole thing tomorrow and you wouldn’t lose anything.” Los Angeles was primed to become one big movie set, a fantasy land, a city of palms signifying “anything goes” — and it did.

Hollywood became the place where not only films were made, but also where the new gods and goddesses of popular culture lived, and their lives became the subject of much scrutiny by an adoring public. Palms were useful in selling Hollywood as a new Mecca, just as they had sold Los Angeles as a desert Eden; the desert realm turned up often in early films in which desert sheiks seduced virtuous-turned-lusty maidens. In the same way, Los Angeles went from Victorian virtue to Hollywood vice: sexiness on screen was an instant hit, and the earliest film fantasies came from the hot, palmy desert. The Garden of Allah (1916, 1927, 1936), The Arab, (1915, 1924), The Sheik (1921), Arabian Love (1922), Burning Sands (1922), Tents of Allah (1923), and The Thief of Bagdad (1924), among numerous others, all portrayed an “Arabia” as imagined by Hollywood. No longer evocative of the Holy Land, Los Angeles via Hollywood was recast as an erotic desert. The Middle East had long represented exoticism, languor, and lust in Western Art, and its incorporation into early films made perfect sense. Now able to depict on screen what could only have existed on a printed page (or perhaps in a stage play), Hollywood writers and directors made full use of what an imagined “Arabian” setting had to offer. And that setting included plenty of palm trees. This trend, combined with the architectural interest in Spanish revival motifs, caused a surge of palm planting in Los Angeles, turning the city into yet another facsimile, a Hispano-Moorish one.

The matchbook cover advertising the notorious Garden of Allah, complete with palms.

The melding of these themes was typified in the Garden of Allah, a Spanish-style hotel with an Islamic name — and palms. Originally named after its founder, actress Alla Nazimova — she added the “h” for “Arabian” glamour — the hotel was located on Sunset Boulevard and became famous for its Hollywood clientele and racy reputation. Of course, the hotel sported palm trees, even using them on its matchbook covers. Palms were also planted at the new fantasy exotic-themed movie theaters, including Grauman’s Chinese and The Egyptian. Klieg lights and palms became a new visual symbol of Hollywood, and Hollywood Boulevard was planted, naturally, with palms.

As the old associations of biblical piety faded away; as the need to promote the city as a “semi-tropical” paradise became outmoded (especially when travel to Hawaii became commonplace) — and when Hollywood began to represent sin, taboo, and sexual openness — the palm was reinterpreted. No longer a link to the Bible or the far-off tropics, palms became a sexy, saucy symbol of a new culture of freedom, pleasure, and individuality. Desert palms could grow — and thrive — in an environment unlike the one in which they originated, much like the hopeful newcomers to the city. But despite their symbolism, palms only thrive in Los Angeles based on artificial conditions — they require water, lots of it, at least two or three times a week — and when abundant water arrived in Los Angeles from the Owens Valley in 1913 and the Colorado River in 1939, the palms’ future was assured.

LATTER-DAY PALMS

A recent wave of immigration to Los Angeles has resulted in another iteration of the palm fantasy. Settlers from actual desert climates, including Iran and Iraq, have built grandiose homes with extensive palm plantings, perhaps in a nod to their native lands — the fantasy of home away from home. Additionally, people from many other climates, including Russia and Asia, have also landscaped their homes with numerous palms, perhaps exulting in the fact that formerly palmless, they now live in a palm-possible environment. Or perhaps, ignorant of the native trees, they assume palms are indigenous to Los Angeles and plant them with abandon. Whatever the reasons, the increase in the palm population has been dramatic.

Yet recent immigrants are not the only over-planters of palms — many longtime residents, ignorant of the native ecosystem, also use palms as a convenient way to evoke their own versions of paradise. How apropos it is that the natural beauty of Los Angeles is overlooked in favor of a false one! Many of these palm enthusiasts are familiar with the contributions to modern architecture by such local architects as Rudolf Schindler and Richard Neutra, whose designs they often appreciate. (They may also be familiar with Los Angeles’s first vernacular architect and visionary, Charles Lummis, whose own handmade house was christened El Alisal after the mighty sycamores surrounding it.) Yet they fail to understand that these pioneers, and many of their ilk, rarely, if ever, used palm trees in their plans, except, appropriately, when designing desert houses. These architects certainly recognized the cliché of the palm in Los Angeles, and more importantly, that palms did not have a place in the environments of integrity and naturalness that they were trying to build. Neutra touches upon this when he stated, describing his Tremaine House:

So the visitor departs finally by the entrance through which he came, takes a final look at boulders, shrubbery, big live oaks, and distant mountain, notes how the architect has reflected the rugged boldness and the hidden delicacy of the scene even in his structural system.

(Richard Neutra, Mysteries and Realities of the Site, 1951.)

Lest palms be banished from all architectural environments, there is one type of architecture in Los Angeles that does call out for palms: Googie. Googie architecture’s unorthodox forms, theatrical overstatement, and disdain of historic styles are the perfect backdrop for the equally bizarre and outlandish palms. A frivolous, lighthearted style calls out for a giddy landscape — what tree could be more suited to this purpose than a palm? (Similarly, Los Angeles’s roadside vernacular architecture also requires a zany landscape treatment that only palms can provide.) Palms, after all, do have their uses.

PALM QUESTIONS

Would Los Angeles suffer if the palms were culled? If native oaks, sycamores, and other leafy trees were to replace a majority of palms, would the city survive? Is the city so entwined with the mythology of its palms that a reduction in their number would create an identity crisis, and would accepting indigenous trees be more than Angelenos could bear? Many progressive Angelenos favor authenticity in a variety of disciplines, from the culinary locavore movement to the restoration of the Los Angeles River basin to a more natural state. Would they not also be in favor of restoring the Los Angeles streetscape to a more environmentally balanced state? Could Los Angeles reinvent itself as a city of drought-tolerant shade trees?

I suggest that it could. To experience the true nature of Los Angeles one need only go to one of its many canyons, where native plants thrive and provide a taste of pre-palm Los Angeles, where sycamore and ceanothus, chamise and sage, manzanita and monkey flower all provide an authentic environmental experience. A return to at least a partial landscape including them, as well as such trees as maple, elder, incense cedar, oak, and laurel would signal a welcome change in the perception of Los Angeles. (Plus some of these trees are delightfully fragrant.) Do we really need to continue pretending that we are a reclaimed desert, or that we are a carefree tropical isle? Are not the benefits of native trees and plants worthy of our attention, especially as water resources are becoming more scarce? (How ironic it would be that the palms, planted as desert symbols, would contribute to the city’s scarcity of water by soaking up too much of it, thereby creating desert-like conditions.)

The palm has run its course: it is time to rethink our attachment to the outmoded fantasies palms represent. Los Angeles, by appreciating and planting its native trees, could expand upon its one-dimensional image and emerge from its palm addiction. Apart from the beauty and usefulness of the native trees, they tell the real story of the city, and do we not deserve the truth? Or is the palm dependence too strong, the opportunity for planting too great, the mythology too entrenched? Are we content with Los Angeles being visualized as a place of grotesque exaggeration, unstoppable frivolity, cultural banality, and overall flimsiness, with the palm tree as its perverse symbol? Was Sumner Spaulding right? Is Los Angeles so chimerical and insubstantial that it is nothing more than stage set? The palms of Los Angeles, histrionic poseurs that they are, would support Spaulding’s claim.

¤

Victoria Dailey is a writer, curator and antiquarian bookseller. She lives in Los Angeles.

LARB Contributor

Victoria Dailey is a writer, curator and antiquarian bookseller. She lives in Los Angeles.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Two Devils in the City of Angels

The following article is from the new LARB Quarterly Journal: Winter 2014 issue. The Journal is now available in bookstores and at Amazon.com...

Levitated Mass Hysteria: Michael Heizer's LACMA Installation

On Michael Heizer's large-scale LACMA installation

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2014%2F07%2Fpalmtrees.jpg)