WITH ALL THE NIFTY craft cocktails at the bar in Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s entry courtyard, the museum is one of the most happening places in LA, a place to be cool even if you have no intention of stepping inside to see the Matisses. But the museum is planning to demolish its core buildings from the 1960s and 1980s in favor of a new megastructure, and if you could take the pulse of the 400,000-square-foot replacement, a fifth the size of the Empire State Building, you would find that its vital signs are faint to nonexistent. The design fails nearly every metric in the museum design book for viability.

It also represents a failure of aspiration: the design is conservative, even regressive, and could have been conceived any time from the 1920s through the 1970s, after which its basically Miesian style fell out of fashion: we learn nothing from the design that we haven’t already known for a half-century. No disruption; no surprise; just comfort Modernism on steroids.

Despite the rosy news and charm offensive now surrounding the proposal as the PR department swings into action on the museum’s 50th anniversary, this is not a brave new progressive architectural world that tests our expectations and expands our thinking. A warmed-over vision, stuck in caution, camouflaged as artistic sensitivity, it even threatens to reverse LACMA’s newly forged charisma: the design is dragging the museum toward mediocrity, sliding it into a yawn.

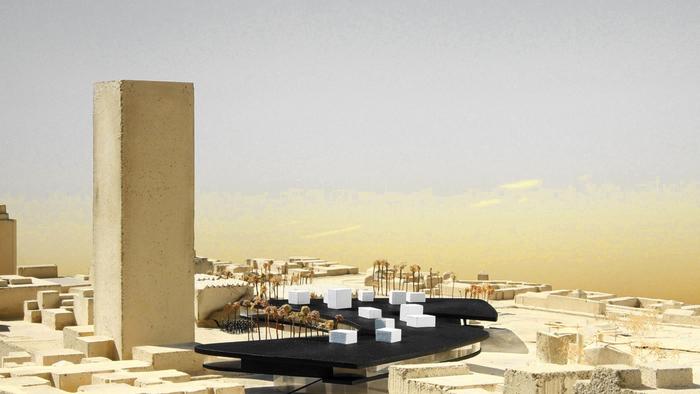

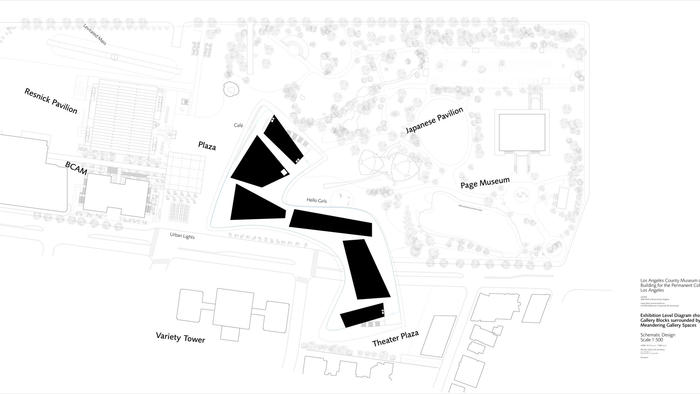

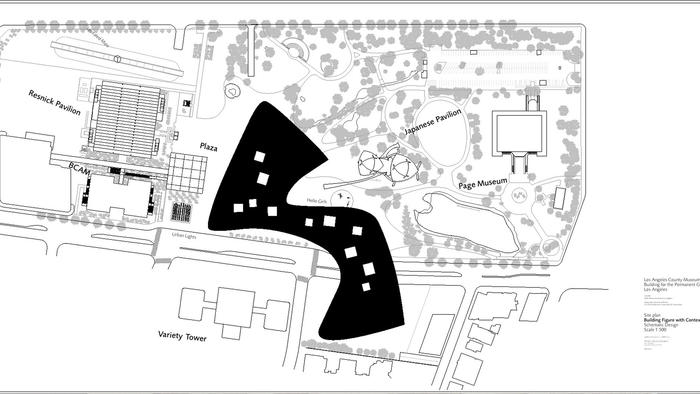

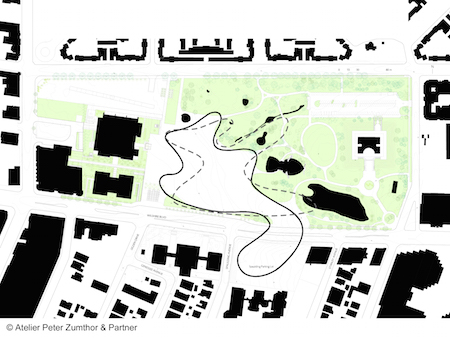

In April the Swiss architect Peter Zumthor and LACMA Director Michael Govan presented to the board the third iteration of a basic design that has been in the making since 2011. What Zumthor has been proposing on this sensitive site is basically a big-box museum, tantamount to a Walmart or IKEA, a giant warehouse with curvy walls propped up on glass cylinders. Zumthor has now divided the galleries into trapezoidal aggregates separated by wide corridors, with the jejune idea that motorists passing beneath the building at 35 mph can glimpse the art and see through the museum, as though it were a drive-through restaurant.

We see a big black amoeba floating 30 to 35 feet above the site and bridging Wilshire, but strangely and perversely, in this city of cars, we see no provision for the additional parking that will be desperately needed (despite a future subway stop nearby); no indication of a loading dock and how it connects to the curving structure; no indication yet for an entrance for schoolchildren and other groups; no detailed plan for the catchall of functions in pavilions at grade, under the belly of the amoeba; no back of house; no event space; no indication of how the ground-floor pavilions, each with a function, relate to one another and to the main second floor; no convincing floor plan yet in the amoeba; no proximity of the collection to the curators’ offices, off-shored to another building on Wilshire; no separation of private and public circulation; no spatial differentiation between the many departments of this encyclopedic museum, each with different spatial demands; no provision for expansion; no sign of the education department; not even any indication of how this massive concrete building with ambitious cantilevers will be structured. A modern museum is an intricate timepiece, but all the cogs and wheels are missing in this watch: all face, no tick.

The design, moreover, is not only dated but also derivative, already an exhausted cliché in Europe, where other curving, swerving precedents undercut any claim to originality and set Zumthor up for accusations that he has been busy at the Xerox machine. His proposal closely resembles similar precedents with which Zumthor would be familiar, such as Auer+Weber’s ESO Headquarters in Germany, and the Rolex Learning Center in Lausanne, Switzerland, by Japanese firm SANAA. The suave curves of the flat amoebic shape — originally inspired, the architect says, by the adjacent tar pool — may now be, in this third iteration, a bit straighter and more angular, but the scheme remains a one-story, elevated, and isolated 10-acre pancake with no connection to the ground and no aspiration to another story that could contain its wasteful footprint. Besides being a one-liner, the sprawling, consistently self-similar amoeba represents a one-size-fits-all approach that consumes all differences in the individual collections in its devouring maw. Despite the flowing, almost ingratiating curves, it’s a single-minded, dictatorial building.

Most inexplicably, the architect has bridged Wilshire to land one pod of the amoeba on a LACMA-owned parcel at the corner of Wilshire and Spaulding, even though there is space to negotiate the blob north on the site, and the possibility of building up vertically on several floors. The pod that lands on the other side of Wilshire kills that large, promising site for either a future museum expansion, or for any high-rise development that could earn the museum substantial annual revenues. The design squanders the site and takes away LACMA’s future, even as it erases its past.

At a debate at Occidental College on March 25, when the third iteration was presented and discussed, Govan dismissed the functional issues as mere details yet to be resolved. (Not to worry, he said: we’ll just pop in extra entrances if and when we need them.) He and the moderator, Los Angeles Times architecture critic Christopher Hawthorne, suggested that what makes Zumthor great as an architect has yet to come — the ambiance of the galleries, the ineffable feeling of his atmospheric spaces. He has a great track record, and he always works like this. Just trust him. Trust the process. He’s on it, thinking about it all in his village in Switzerland. It’ll be great.

Ironically, and sadly, they were saying the design should not yet be judged by the drawings and models that are already on the table, even though the architect has been working on the same basic design for about four years. What’s now on record is sketchy, a study in design procrastination, and what’s off the table and so far unknown, apparently unresolved, are the fundamental issues and functional criteria that would make the building work: this curvaceous black body has no organs or bones, no evidence that shows how the building integrates into a functional whole all the moving parts and vital organs of a complex program on a demanding site. It even fails at the level of the basic diagram, which is simplistic. His supporters and apologists say that he is still “working through the materials, the planning of the structural systems, entry sequences, and galleries,” as Sarah Williams Goldhagen put it, to achieve the “emotionally rich, monumentally authentic presence of his celebrated spa [at Vals, Switzerland],” but the explanation for the sorry incompletion of even his conceptual scheme at this point does not mask its fundamental shortcomings. Repeated requests to LACMA for clarifying drawings were declined on the grounds that they don’t yet exist or are not ready.

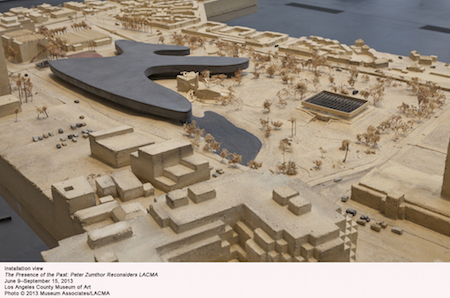

What we have seen in a large introductory 2013 exhibition, “The Presence of the Past,” and in the two subsequent updates, demonstrates that the design fails at a level that makes the question of the materials, entry sequences, and galleries moot: there is no basic cake to support the icing.

Announcing the revisions in this third iteration recalls Nero fiddling. The architect is tinkering with an underdeveloped and fundamentally inadequate design by offering, for example, two rather than four entrances and occasional double-height galleries with skylights. The tweaks are trivial. He is assuming that the concept is just fine, but in fact he is not solving basic problems: instead he is stuffing functions into, and beneath, what is basically a box with curves — a closed, stranded, and stratified form — rather than growing the building organically from how the building works both internally and externally. The functions that he has ignored or put off are forces that should be harnessed to drive the design from its conceptual inception. They are like the pigments with which artists paint their canvases, a sine qua non of the work.

Zumthor’s compatriot architect Le Corbusier believed “the plan is the generator,” but for Zumthor, the image is the generator — and what we have seen are images of the black blob from all angles, at night and during the day, oozing around the site, taking a running jump to leap across Wilshire. Is it churlish to ask for a site plan at ground level to see how the undercarriage of glass pavilions relate, and what they actually do? How people get up into the building? How art is delivered to service areas and the galleries? It’s a handsome proposal in the way a Ken doll is handsome: good-looking but vacant, despite being delivered by a reclusive architect with the aura of a prophet who has come off the hill to levitate our expectations.

The board should be very worried, and it would be well advised to press the pause button and seek second opinions from other architects invited to submit alternative schemes — much as we seek a second opinion from another doctor. The board should open up what has been a very closed process, a conversation primarily between Govan and Zumthor — with some public comment but no actual input. Instead of hailing the project as a welcome addition rescuing LACMA from its disappointing architectural past, the Los Angeles architecture community is already deeply divided about the plans, and the professional opposition is basically the canary in the coal mine. Out of professional courtesy and fear of LACMA’s institutional power, few architects will speak on the record; tellingly, very few have come forward with expressions of support.

The issue is not one of style but of organization, function, scope, and common sense. All told, the Zumthor proposal is not an improvement over the existing complex, and so does not make the case for justifying the replacement of the current structures at huge expense: it looks and is different, but it has as many shortcomings, just of a different sort.

WHAT WENT WRONG?

When the American economy tanked in 2008, the bewildered W asked his cabinet: “How did we get here?” During the debate at Oxy, Govan inadvertently explained just how LACMA got into this predicament. The museum made two well-intended but erroneous assumptions. “The easy part,” said Govan about why they called Zumthor off the mountain, was because “he’s designed some of the most extraordinary galleries in the world.” The second assumption was that the galleries of the museum should be on one floor only: “every floor you go up, you lose visitors.” Govan added that retailers never want to be on a second floor because foot traffic halves with each subsequent floor.

Govan is the driving force behind the LACMA project, not only because he’s the director, but also because he is a director with the DNA of a builder: early in his career he saw firsthand how architecture can define institutions and positively condition the viewing experience. Soon after graduating from Williams College, and while an art student at the University of California, San Diego, he was tapped to become the deputy director of the Guggenheim in New York, where he worked on Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim in Bilbao. Later he decamped to the DIA Foundation in New York, where he convinced the board to abandon its facilities in Chelsea to move lock, stock, and barrel to a repurposed Nabisco factory in Beacon, New York, on the Hudson.

His mold as a director was cast through these formative experiences. Early on, analyzing the experience of seeing art in the Guggenheim as opposed to museums like the Museum of Modern Art, he spoke insightfully about warm vs. cold space: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim provoked a subjective, emotional experience on the part of the viewer, through its use of natural light, curving forms, and exalted volume, all of which conditioned the perception of the viewers, putting them into a receptive state for viewing art. On the other hand, he called museums such as MoMA “ Newtonian,” in that their white cube galleries represent a cold, indifferent universe, each object orbiting on its own in evenly lit spaces: space here is clinical, each artwork an artifact of objective examination, as though galleries were surgical theaters. At DIA:Beacon, he hired California artist Robert Irwin to conceptualize the museum, working in association with the architects of OpenOffice; and Irwin, who has pursued the phenomenology of perception in his work by understanding light in space, created a Minimalist environment that featured natural light as a primary building block of the interiors and the viewer’s experience. Govan also hired Zumthor at DIA:Beacon to design a small adjunct building, which was never built. Zumthor had built his shadowy, very atmospheric spa at Vals, Switzerland, in 1996, with textured walls raked by natural light. Zumthor, also interested in phenomenology, was part of the same Minimalist clan, a card-carrying member of its architectural branch.

Govan, who as an art student was interested in space and light, has co-authored Dan Flavin: A Retrospective, about the Minimalist who famously created fluorescent pieces and environmental installations that basked in their glow. Govan’s interest in environmental Minimalism is authentic, and his position about warm vs. cold space is perceptive and relevant, especially as artists have challenged rationality, scientism, and linear thinking in a world gone objective.

With this background, Zumthor seemed a natural choice at LACMA for Govan, although there was a danger that Govan would be commissioning Zumthor as he did Irwin, more as an environmental artist than as an architect. Zumthor is an architect who manipulates light on textured, materialized surfaces to create atmospheric effects. Besides the spa in Vals, he has created two small atmospheric museums, the four-story, 20,000-square-foot Kunsthaus Bregenz, Austria (1997), and Kolumba (2007), a 16-gallery museum in Cologne, Germany, built around the ruins of a Gothic church destroyed during World War II. Although the exteriors are generally cubic — simple, not very expressive, but beautifully textured boxes — the interiors are remarkable exercises in Govan’s warm space: Zumthor creates moods that appeal to the senses of the viewer, telegraphing that they are in zones of special experience. Kolumba’s exhibition rooms are indeed serene and beautiful.

Serenity and beauty alone, however, will not suffice at LACMA. What might be called “atmospherism” has worked in two highly specialized, small, boutique museums, but extrapolating Zumthor’s formula cannot work in an encyclopedic museum like LACMA, which has a much more complex mission. The past and current plans for his 10-acre pancake show an equal, leveling treatment of all spaces, which is perhaps fine in the much smaller Cologne museum, and for Bregenz, a Kunsthalle of changing shows. But LACMA has 16 different departments — American Art, Chinese Art, Costume and Textiles, European Art, Photography, et cetera — and each collection wants spaces of its own, scaled and nuanced per the character of the objects. The light level, dimension, and tone of the spaces should resonate with the nature of each collection. Chinese art might not thrive in a contemporary European ambiance. There is no single contextual narrative applicable to all collections. Zumthor’s timeless interiors exist outside time, in a realm of sensation, not history.

Instead of a program-driven architectural response, Zumthor’s uniform interiors steamroll all collections onto a single, undifferentiated floor, creating a totalizing environment that thrives on the rule rather than the exception, on atmospheric mystification rather than culture and history. His highly aestheticized interiors are at cross-purposes with a museum like LACMA, with its multiple institutional roles. In this third, recent iteration, the double-height spaces Zumthor popped in do not help — none of the objects currently in the collection need the heights doubled to this monumental scale, so the formal manipulation of the spaces does not help explain the collections, and may create galleries oversized for the art. They simply relieve some of the monotony of the pancake as they allow natural light, the clay of his architectural imagination, into the spaces. The new heights respond to his own spatial needs as they solve a problem of Zumthor’s own creation.

As an encyclopedic museum, LACMA uses its collections not only for aesthetic display but also for explanation, research, and instruction: it is an institution with a learning mission. According to a professional staff member who spoke on the condition of anonymity, in the only meeting Zumthor had with the entire curatorial staff, he made an alarming remark offensive to some curators: “I am talking about the experience of art,” he declared. “I don’t want art historians to tell me what’s important.” The peremptory remark revealed his hand, an exclusionary attitude — the eye über alles — confirmed by his already established track record in his two earlier museums. At Kolumba, his curatorial premise is an aesthetic narrative of beauty and juxtaposition: the idea that a Gothic thing hung next to a contemporary thing on a concrete wall — with plenty of space in between and no written texts or chronological order — reveals something about both. This is wit in the way Samuel Johnson defined it: “the unexpected copulation of ideas, the discovery of some occult relation between images in appearance remote from each other.”

The curatorial wit at Kolumba may succeed in the limited confines of the Cologne museum, with a small collection — sometimes just several objects are displayed in a whole gallery — but it’s the wrong paradigm to graft onto LACMA. Curators at LACMA have their own mandate to explain and study their collections, and juxtaposing different forms of beauty in a uniform space severely restricts their ability to use their collections to explain their collections: the design presumes a single aesthetic narrative in a generalized space rather than a narrative that might emerge from the objects in the collection themselves. Marcel Duchamp criticized 20th-century art for being “retinal” at the expense of content, and Kolumba is mostly retinal.

In one early meeting introducing the design, Zumthor dropped a bombshell of a proposal that was largely overlooked: he said that the gallery walls would be concrete. Few people understood the serious consequences. While the concrete might help create “atmosphere” and a sense of authenticity through its indisputable materiality, especially compared to the abstraction of white walls surfaced in sheetrock, concrete walls commit the museum and all its departments to a fixed plan that will restrict changing wall configurations, and restrict, too, the frequency of exhibit changes, not easily done on concrete walls. The concrete walls and ceilings, by now an aesthetic formula carried over from Bregenz and Cologne, also monumentalize the interior, creating scale problems for more intimate collections.

The totalizing uniformity of the design reveals an underlying top-down authoritarian attitude of both the geometry and the designer. Zumthor has not grown the concept of the building from the detail, by listening to the programmatic needs of the curators, but from the simplistic a priori notion that this amoeba is a silver bullet for the site, a morphology cleverly able to bend where necessary and convenient. Just as Zumthor has not used the fundamental forces of the site — parking, entrance, crowds, flow — to shape the building, he has not allowed the museum’s programmatic forces to generate the form and the interiors. As Victoria Newhouse’s book Art and the Power of Placement makes amply clear, there is more than one way to view a work of art. Plural environments are necessary for plural collections. At LACMA, curators have not had sufficient input in a process in which “historians” need not apply. As Govan noted at the podium, several came to the debate to see what the plan was like. They didn’t know.

THE MUSEUM AS RANCH HOUSE

Govan’s other assumption is that a single floor best serves a museum; he theorizes that horizontality fosters an ease of wandering, as in a park. Even if any precedents for encyclopedic, parklike, one-story museums of LACMA’s scale were to come to mind (the Louisiana in Copenhagen, for example, is instead a small, domestically scaled museum), the observation is inexplicable given Govan’s own firsthand experience at the New York Guggenheim. Wright had a relatively small site for the amount of art eventually to be displayed, and rather than creating a seven-story museum stacked like pancakes seven high, he ramped the galleries in a continuous spiral around an expanding and commanding atrium, natural light feathering its curving white railings. The clever fact about the Guggenheim’s organizational concept is that the master basically created a single street and a one-story museum to be experienced as a continuous promenade without stairs. Visitors wander around on a linear path, dipping alternately into the art hung on the sloping walls and into the vistas across the atrium. It is a stroll.

LACMA’s own Pavilion for Japanese Art, by Bruce Goff, a friend and admirer of Frank Lloyd Wright, has a similar circulation pattern, though the spiral occupies the center of the space, not the perimeter. Govan doesn’t have to look far for how to figure out how to wander in a multistory museum.

The precedent is clear for any museum worried about getting visitors to a second floor: an architect with geometric range can deploy a spiral, or a figure eight, or loops, or ramps, or terraces, or a variation of Möbius strips to create a continuous promenade through two or more stories of a building, all the while creating a one-story experience, as Wright did. But even if the geometry is restricted to the right angle, consider the success of the grand staircases of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Louvre in Paris, the National Gallery in London, and the Art Institute in Chicago at enticing people past the ground floor and up into the galleries. Although all are designed in a classical language unsuited for Los Angeles today, the staircases invite visitors upstairs via the spatial generosity of wide, easily traversed ceremonial stairs that open alluring vistas above. The architects have designed spaces that provoke the desire to see what’s next: greeted by the generosity, visitors are led by their curiosity.

Los Angeles’s own Thom Mayne, of Morphosis, has made a specialty of updating this classical precedent by reinventing the typology of the grand staircase, creating wide staircases that climb high, deeply, and invitingly into interiors they activate and dynamize. Like the Piazza di Spagna in Rome, the stairs are really public spaces fostering civic gathering and social encounter, and they are “warm” in Govan’s sense: they engage the imagination and emotions of the visitor. There is in fact no reason that LACMA can’t start at grade, with some of the galleries accessible on the ground floor, leading up, via a generous staircase or a continuously looping promenade, à la the Guggenheim, to a second floor and beyond.

The staircase is not dead or deadly. You can still judge architects by the way they invent flights into the third dimension.

Ironically, the Zumthor proposal is already a two-story museum since the pancake rests on a full story of catchall glass cylinders containing various programs, though still waiting to be completely identified. By Govan’s own argument, the museum has already lost half of its potential visitors by lifting the pancake off the ground. The design defeats its own one-story argument.

Many multistory museums place their curators and staff on a top floor to ensure proximity for curators to their charges. Protective of his artist-architect, Govan says, however, that Zumthor needs to bring in natural light to the galleries, meaning that an additional floor would prevent the skylights into the spaces Zumthor stages for light. Govan should be the first to remember that Frank Gehry solved the topography of light in the multistory Bilbao Guggenheim by inventing chimneys that channel natural light from skylights to lower floors. He did the same in his recent design for the Vuitton Museum, creating luminous galleries even on lower floors.

If Zumthor’s adherence to Govan’s one-story theory compromises the interiors, the results are disastrous for the site. At a time of increasing urbanization for America’s quintessentially suburban city, Zumthor’s pancake has condemned the museum to sprawl on a site that has a limited amount of square footage. Govan inherited a campus that was expanded in 2008 by the closure and absorption of Ogden Avenue at the west flank of the original LACMA campus, and by the 1994 acquisition of the May Company building at the corner of Fairfax and Wilshire, with its extensive parking. With the pancake, Zumthor is now squandering that spatial inheritance.

But the one-story policy has already been chipping away at the campus. The recently built Resnick Exhibition Pavilion, all 45,000 square feet of it, is a single-story structure that gobbles up as many square feet: with a more spatially supple concept, the pavilion could have easily been organized on a couple of floors, saving half the square footage for future development. The spectacle of erecting Michael Heizer’s Levitated Mass was certainly an entertaining feat of Barnum & Bailey bravura, particularly the heroic march of the cyclopean rock through Los Angeles. But the piece devours a huge amount of land. With these two projects plus the pancake, Govan is spending LACMA’s land unsustainably. Zumthor’s current plan to bridge Wilshire, landing one pod of the amoeba at the Spaulding site, represents a confiscation of both LACMA’s remaining land, and its future. Even if Zumthor’s plan were worth saving, it could be reoriented within the LACMA site north of Wilshire, with some adjustments. But even that alternative, which would spare the Spaulding site, is untenable because the footprint is still spendthrift.

Using up the Spaulding site is not only unnecessary, it unravels LACMA’s hard-won achievements at museum-building over the last generation. When Robert Maguire, the prominent and famous Los Angeles developer, entered the LACMA equation as a board member in 1981, and then as board president from 1990–’94, he completely changed the game in the most Los Angeles way: land acquisition. The museum, which is still cashing in off his achievements, is able to expand largely because of his foresight. (He is still on the board.)

A developer and businessman, Maguire thinks like a developer and businessman, one enlightened by civic concerns. His first achievement was to reset the financial operating agreement with the county to guarantee a regular base income. In a sensitive but ultimately successful and highly advantageous deal, he also acquired the May Company building a block west of LACMA, with its contiguous acres of parking. He later acquired the Spaulding site across Wilshire for either future expansion or for developing (another parcel at Wilshire and Ogden was acquired in 2008). The 87,000-square-foot Spaulding site can support a 25-story commercial or residential high-rise, and the 30,000-square-foot Ogden site, about a nine-story building. Maguire’s vision was not only civic but also entrepreneurial: his acquisitions set the museum up to generate income that will be lost with the pod at Spaulding. (Govan has said that Frank Gehry might design a structure on the Ogden site, though the whole project is conjecture at this point.) Of the two sites, Spaulding is clearly more valuable.

While Govan’s background understandably leads him to pursue beautiful galleries, the real task of LACMA’s leaders is a comprehensive vision for not just the galleries and collections but also for the whole site, including its two valuable parcels across Wilshire. Before the board approves Zumthor’s confiscatory scheme, there should be a land-use study of LACMA’s campus and associated real estate, along with a long-range museum plan to see how best to use the land in budget forecasts: there is no reason a museum should not be entrepreneurial, especially when its previous directors have set up the potential. MoMA famously has used, and is using, its air rights to develop very tall residential towers above its campus to generate perpetual revenue streams for the museum. LACMA has the land available to do the same. The new subway stop on Wilshire at Fairfax will give added commercial value to LACMA’s properties, but in addition, LACMA is able to create value on its parcels by theming the development comprehensively as an arts district, like New York’s Museum Mile, and developing both its parcels in a coordinated vision. LACMA’s prestige creates value across all its sites, so comprehensive land planning, in the context of urban planning for the area, would bolster long-term strategic economic planning. Entrepreneurship should be part of the planning equation.

Neither Zumthor nor Govan seems particularly bothered that the curators and associated professional staff are being exiled off-site because of the one-floor policy, a relocation that curtails a close relationship between curators and collections. But in addition to curators losing proximity to their collections, the museum will have to rent many more stories of office space than the 1.5 stories it now already leases across the street at huge expense (over $1 million a year, according to one source). The museum is not only losing rental profits in an expensive district; it is also paying out of pocket prices elevated by the prestige of its own presence across Wilshire. It’s working against its own financial interests by effectively raising its own rents. The trade-off is fiscally punishing — and no way to run a business.

During his chat from the Oxy podium, Govan noted that the roof of the Zumthor pancake will be covered in solar panels that will allow the museum to sell energy back to the utility grid. But the money saved and made on energy generation is trivial compared to moneys lost either to off-site rents or unrealized profits on the Spaulding parcel. LACMA can hardly afford not to develop Spaulding.

Revenue is, as always, an issue, as the museum sadly learned during the financial downturn of 2008. The recession set in and LACMA put on hold its plans to use the May Company building for many needed uses: flexible gallery space, administrative offices, education space, and study centers for the departments of costume and textiles, photography, and prints and drawings. The administration finally had to shelve its plans and lease the building for 55 years to the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures. The functions that LACMA had planned now seem to be orphaned, or at least unaccounted for in the Zumthor proposal, though Zumthor seems to be meeting with the curators of some departments about their storage needs. (Off-site storage is already insufficient, and also costly.)

Civic museums like LACMA typically need to expand every 10 or 15 years, so it’s predictable that even with any square footage added by the Zumthor scheme, it will need to expand twice within the next 40 years. Because the current plan exhausts the site and the form arbitrarily precludes any addition, Govan was asked at the Oxy debate how the museum would expand in the future. He answered, disingenuously, that it could expand south of Wilshire, without clarifying that this would be a hard sell to the denizens of a dense existing residential complex immediately south of the Spaulding parcel, and that the area is zoned for residential. He also suggested, somewhat cavalierly, that LACMA could eventually establish satellite museums, even though satellites have failed in other cities, or have succeeded only with substantial governmental funding.

There is no spatial reason the new replacement museum can’t be kept on the north side of Wilshire. Even if the space-guzzling four-acre Zumthor building were repositioned solely on the museum campus, it still wastes land because of the one-story premise. The game suddenly changes, however, if the museum’s requirement for a single-story structure is lifted. The limiting factors are actually Govan’s assumptions and not the site itself, which is probably large enough to accommodate a couple of subsequent multistory expansions. It is even possible that well-planned, phased, multistory expansions could continue until the lease on the May Company building expires in about 50 years, and LACMA can reclaim the structure and adjacent spaces.

PARTING THE CURTAIN ON THE WIZARD OF LACMA

Isaiah Berlin’s famous essay “The Hedgehog and the Fox” analyzes how the hedgehog knows one big thing, and how the fox is, well, foxy, and knows many things. Berlin characterizes writers and thinkers mostly as one or the other. He might have written the same essay on architects.

Zumthor is a hedgehog.

What the Swiss architect indisputably knows how to do well is create atmospheres inside his buildings, the warm, subjective universe that Govan correctly admired in Wright’s Guggenheim and Zumthor’s Kolumba. Zumthor’s originality was to reject architecture’s Post Modernist interest in language as a basis of architecture and turn to basic materiality. He is most famous for his baths at Vals, where he creates hidden sources of natural light that wash lapidary walls surfaced in fine layers of quarried quartzite. Baroque architects of course did this centuries ago, but Zumthor dramatizes light in an undecorated Modernist idiom through the use of materials, such as concrete and stone, which embody a sense of authenticity due to their sheer physicality. He orchestrates entire environments to cultivate atmospheres, not just singular moments, resulting in spaces that are light-and-materials installations akin to the installations of the Light and Space Minimalists with whom Govan has a special affinity.

Zumthor is like a 19th-century Luminist painter, specializing in light in architectural landscapes. But whether a contemporary artist or a throwback to the Romantic era, he designs spaces with a luminosity and stillness that implicitly critique more exercised designs by such architects as Frank Gehry, Zaha Hadid, and Thom Mayne, who are sometimes viewed as formalists creating what one Zumthor fan incorrectly called “histrionic” buildings. Zumthor represents one end in architectural debates currently polarized between complexity and simplicity. In choosing Zumthor, LACMA has taken sides in a broader polemic, becoming both a testing ground and a battleground.

For Zumthor’s atmospherics to work, he simplifies and reduces the architecture so that nothing disturbs the effects, much as in an installation by Doug Wheeler, James Turrell, or Robert Irwin. You can hear a pin drop in the quietude of his reductivist spaces; a stray matchbook collapses the design. And you don’t want too many people in his rather holy spaces, certainly not the crowds that LACMA already hosts on a busy weekend. Zumthor’s simplicity comes at the cost of the rigid, exclusionary discipline necessary to cultivate light, texture, and mood without disruption.

Although Zumthor’s office says that what drives its design philosophy is the cultivation of experience rather than form, the result is a soft species of form-for-form’s sake, a formalism that might be called “atmospherism” or “elementarism.” The fear is that Zumthor’s atmospherics are a Trojan horse that surreptitiously takes over the museum’s curriculum from within with its own demanding, commanding aesthetic agenda. The “atmospheric” concrete walls severely restrict the museum’s adaptability, and that the curators themselves are being moved off-site signifies that the design has usurped the museum functionally and symbolically.

Even senior curators have been precluded from a significant role in the formulation of the program. In the rather secretive and private design process, Zumthor’s conversation has been primarily with Govan in what has emerged as a top-down process that minimizes what lawyers might call “discovery” at other levels of discussion. Govan is basically treating Zumthor, as he treated Michael Heizer during their collaboration on Levitated Mass, and Chris Burden, on Urban Light, as an artist rather than as an architect. The museum design has evolved more as an art project than as a building.

Govan’s respect and protectiveness for artists is commendable, and by background and predilection, he is especially susceptible to the work and personas of artists interested in the phenomenology of perception. He is not alone. Because these artists — Wheeler, Turrell, Irwin — handle light, the mystic material, they seem to deal in art of a higher order, and when they come off the mountain into the flatland of everyday reality, as Zumthor has, they arrive with an otherworldly aura. Some allow themselves to be treated as cult figures, planing above the fray. Many of Zumthor’s spaces in Europe evoke religious feelings, just without the religion. Most of Los Angeles’s critical establishment, apparently mystified by the Alpine prophet, is virtually supine in front of the proposal, offering little critical perspective and certainly no resistance.

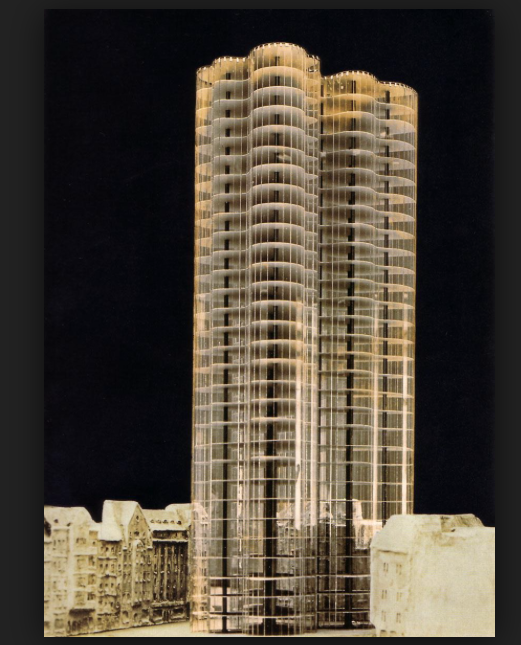

But parting the veils of Zumthor’s environmental mysticism reveals an Oz at the organ. If you strip the design of what everyone assumes to be its inevitable aura and you peer through the seductive penumbra, you find, basically, a Miesian box enclosing impersonal universal space: the infrastructure supporting the environmental warmth is ultimately cold, underdesigned, simple to the point of simplism. As noted in a previous article, Zumthor has basically transposed to LA one of the undulating floor plates from an unbuilt tower Mies proposed for Berlin in the early 1920s, a curvaceous variant of a box: a closed form. There is a sad irony in finding Mies at LACMA because, back in the early 1960s, the museum considered but rejected him in a controversial turn of events. To build a Miesian project after more than 50 years denies that any progress has been made in the field — even if the Miesian infrastructure has been warmed over with atmospheric effects.

A second irony is that, contrary to many European and East Coast prejudices about Southern California, Los Angeles does have strong traditions of architectural Modernism that provide a suitable reference, even a point of departure, for the design. Mies and Minimalism are antithetical to that tradition. Frank Lloyd Wright and Japanese architecture, which influenced Wright (and Greene and Greene in Pasadena), are at the root of a tradition that includes R. M. Schindler, Richard Neutra, and following architectural generations, including Frank Gehry. Wright famously “broke the box” of European architecture and developed an organic architecture that related to the land, which has been a fundamental source of American identity since the 19th century. Wright broke the box horizontally, with wings of his houses reaching into the landscape, and Neutra followed suit, translating Wright’s insight from organic wood and brick into industrial steel and glass. Schindler, building houses on Los Angeles’s hillsides, broke the box vertically, creating terraced sections in which houses became ladders stepping up and down the slopes. The influence of Japanese architecture through Wright (and the return of GIs from the Pacific front after World War II) confirmed the openness of American, and California, architecture to the landscape.

Rather than the closed Euclidean forms coming out of Europe via Mies and the Bauhaus, the California Modernists opened form in highly specific site-sensitive designs that rejected universality in favor of singularities — moments of specific architectural response to the views, the slopes, the sun. They favored complexity over simplicity because complexity elasticized their responses to the demands of complex sites and programs. When Schindler looked at Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye house of 1931 outside Paris, an icon of European Modernism, with a white concrete box of living spaces set atop a loosely organized base of catchall functions and columns (much like Zumthor’s scheme), he called it “infantile.” Schindler would say the same of the Zumthor design. As a conceptual diagram of a box perched on columns, the Villa Savoye and Zumthor’s LACMA are not that different, despite 85 years of separation.

If Govan hadn’t required a single-floor solution, Zumthor would probably have responded with the multistory pancake structure already in his repertoire. In the Kunsthaus Bregenz of 1997, he stratifies vertical space into a spatially mute four-story stack of pancakes bounded by walls and ceilings made of polished concrete. He connects the stratified floors with a mean, steep flight of steps tacked onto the back like a fire escape. Missing is a staircase that might otherwise have integrated floors for curatorial continuity. Zumthor is a planimetric architect who doesn’t develop space with any complexity in the third dimension: he stacks closed boxes.

As an architectural fundamentalist who seems to have taken some sort of monastic oath, Zumthor prides himself on designing mostly with physical models, and he eschews the computer. But by denying himself the use of this potent tool as part of the design process, staying resolutely analog in the interest of authenticity, he also limits the scope of his architectural response. In the case of the LACMA project, the ability to capture space vertically is critical, and geometry is key. Zumthor is not playing with a full geometry book: pages are missing, especially the whole computer chapter, and LACMA is the poorer for his professional blinders.

Even if he misses LA’s architectural context, he did attempt to respond to the immediate physical context by mimicking the contours of the adjacent tar pool. However, the idea is literally superficial, and the poetry anemic. First, he took the pool at face value, as a two-dimensional surface, which translated to the main museum floor as a plane without vertical dimension. Second, in one of the most perceptive comments made during the Oxy debate, architecture critic Greg Goldin noted that what we think of as the site’s Ice Age tar pool once swallowing Paleolithic creatures is actually an anachronistic asphalt quarry that has since filled up. Zumthor’s effort at poetic allusion and contextual empathy are sorry attempts.

There are many flaws to the project beyond the two large fallacies, the single story and the tyranny of atmospherics. Among the most dubious features are the glass pavilions in the underbelly of the pancake — which we hear about, but do not see in any available plans — that will house certain functions like the conservation labs. Zumthor proposes glass enclosures for the labs: although the notion of transparency seems attractive because of the vaguely democratic notion of visual access, certainly the conservators, who frequently stand in front of a painting for hours appearing to do very little, don’t want to be caught like fish in a bowl as spectators press their noses up to the glass. Little knowledge is to be gained, and much privacy, and contemplation, to be lost.

But perhaps the most alarming issue is the size of the building, and its elevation 30 to 35 feet above grade (three full stories). Zumthor has said that he has resolved the issue by allowing the visitors to see the museum at a glance at arrival in an overview, but there are many successful museum buildings that have a knowable plan revealed by a main explanatory staircase, or museums that are knowable on a promenade through an unfolding experience. As mathematical biologist D’Arcy Thompson explained in On Growth and Form, a classic early-20th-century book well known to architects, there are limits to growth and to what a single morphology can support. Some 400,000 square feet on a single floor is unwieldy, and an amoeba would have long since given up and surrendered to mitotic subdivision.

Zumthor seems to be learning on the job, and in a letter read at the Oxy debate, the architect says the project has taught him a great deal about scale. He wrote that in order to keep the scale manageable, he has discovered that visitors must understand the building at a glance, so he eliminated two of the four original entries (previously a big selling point), a perimeter verandah (previously a big selling point), and simplified the building so that it can be more easily grasped from only two entries. This late eureka moment for an architect who usually works at small-to-medium scale is not very reassuring, and his correctives might create other problems, such as the daunting prospect of an overwhelming first impression. The leap to a 400,000-square-foot project for an architect who has mostly done jewel boxes is perhaps too much to handle: LACMA is twenty times larger than Bregenz. A project of this size and complexity really demands a fox who has survived many hunts.

The quality of the space in the underbelly of the galleries gives equal cause for concern. Many observers have compared these covered spaces to freeway overpasses, but no overpasses in Los Angeles are as wide, deep, continuous, and potentially as crushing as the space beneath this looming structure. They are sunless areas more appropriate for mushrooms. Govan says the spaces can be brightened up with cheerful tiles. This is a Band-Aid, inadequate for the larger wound.

WHITHER?

With this third iteration, Zumthor confirms the direction of his design investigation: the tweaks don’t change much. Thank you. But whatever the reason, the current scheme fails on so many levels that LACMA owes it to itself and its curators — not to mention to the citizens of LA County — to consider other solutions. Any laissez-faire attitude on the part of the administration about the ongoing design process risks backing the museum into a premature approval of the design.

A complicating factor is the gun now pointed at the temple of the museum. Univision mogul A. Jerrold Perenchio is bequeathing a $500 million gift of art to LACMA, contingent on building the Zumthor scheme. No one knew before the gift that Jerry Perenchio was so committed to Swiss architectural Minimalism. Perhaps Mr. Perenchio didn’t know either. The contingency clause, of course, smacks of a backroom deal forcing the museum into a shotgun wedding with the design, and it amounts to cultural blackmail, unseemly and actually sleazy for an institution that should behave by elevated ethical standards. A private party is hijacking a public institution. It might be appropriate for the gift to be made on the condition that a new museum replace the old buildings, but no donor should be able to coerce the museum into a building that fails the museum on so many levels. Moreover, no self-respecting museum should honor those terms. One suspects that the contingency clause was not a total surprise to Govan, a capable fundraiser and social engineer who has shown the behavior of a very clever fox on many fronts since his arrival in LA. That’s why he’s been so successful at repositioning LACMA. There are, however, some foxholes a clever fox should not jump into.

Rebuilding LACMA’s core is a complex problem that wants a complex solution, and in many ways the problem is not architectural but administrative. To be comprehensive, the brief should be formulated as a land design problem, a height design opportunity, an encyclopedic museum responsibility, a civic issue, an environmental mandate, an urban initiative, an iconic desire — as well as a display question, not as an art commission.

Without a clearly stated and comprehensive mandate, and with Zumthor’s limitations, the scheme shows few of the responses necessary to answer all the issues tugging at the commission. The simplicity is at once a naive response and an arrogant imposition, restricting numerous functional needs and institutional goals to an ink-blot formalism that pedestalizes galleries as vessels of light. On the one hand, Zumthor and Govan are entirely correct to focus on the quality of experience in the galleries, because no museum should be built without a valid curatorial attitude about how to display, experience, and explain the art. But the approach to the galleries should not come at the expense of the rest of the building, the museum’s basic mission and programs, the needs of its curators, the conceptual integrity of the collections, the site’s urban potential, and its future space and budget planning. The plan must reflect an integrated overview of the museum as an institutional whole, and not just feel-good, look-good atmospherics.

The rush to accept a weak organizational diagram, a wasteful campus plan, and a poor urban strategy in anticipation of a rich ambiance has left too much of the larger picture unaddressed and undeveloped. Parting the green curtain on the architect behind the design reveals that all the anticipated atmospherics rest on a very thin architectural foundation, one incapable of carrying forward LACMA’s full institutional mission and architecture’s own potential as a progressive, inventive force.

Instead of rubberstamping the project on the basis of small incremental revisions, the board has the responsibility, not to mention the fiduciary duty, to stop the train before it leaves the station. The better part of a billion dollars and LACMA’s future over the next 50 years are at stake.

¤

LARB Contributor

A Pulitzer nominee in criticism who trained in architecture at Harvard, Joseph Giovannini has led a career that has spanned three decades and two coasts. He has served as the architecture critic for New York Magazine and the Los Angeles Herald Examiner, and was long a staff writer on design and architecture for The New York Times. On a contractual or freelance basis, he has contributed to many other publications, including The New Yorker, Architectural Record, Architectural Digest, Art in America, Art Forum, Architecture Magazine, Architect Magazine, Industrial Design Magazine, and Interior Design.

A prominent figure in American architecture, he has been an activist critic with a record of discovering emerging talent for major mainstream publications and professional journals. He coined the term Deconstructivism during articles he wrote announcing the movement. Giovannini has written literally thousands of articles for periodicals, and he has also authored numerous essays for books and monographs. As a critic, he has won awards, grants and honors, from the Art World Magazine/Manufacturer’s Hanover Trust for distinguished newspaper architectural criticism, the National Endowment for the Arts, the Graham Foundation, the Los Angeles Chapter of the AIA and the California Council of the AIA.

He has put theory into practice in his own architectural practice. Mr. Giovannini heads Giovannini Associates, which has recently completed the conversion of a large trucking warehouse into a community of lofts in Los Angeles, and a 19th-century commercial building, also into lofts. A bicoastal designer, he is currently working on several apartments in New York and lofts in Los Angeles. His lofts, apartments, galleries and additions have appeared in Architectural Digest, Los Angeles Times Magazine, A + U, Domus, House and Garden, GA Houses, Architekur und Wohnen, Sites, and Interior Design.

He has taught advanced and graduate design studios at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, UCLA’s Graduate School of Architecture and Urban Planning, the University of Southern California’s School of Architecture, and at the University of Innsbruck. He holds a Master in Architecture from Harvard’s Graduate School of Design. He did his B.A. in English at Yale University, and an M.A in French Language and Literature from Middlebury College for work done at La Sorbonne, Paris.

LARB Staff Recommendations

In the Dead of Late August . . . Zumthor’s LACMA Folly Continues

Distinguished architecture critic Joseph Giovannini on Zumthor’s LACMA folly still going on….

Response to Sharon Johnston and Mark Lee

Sharon Johnston and Mark Lee defended Zumthor's LACMA plan; not very well, says Joseph Giovannini.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2015%2F04%2F140624_Night-Facing-West_Edited_labeled.jpg)