AFTER ENOUGH TIME in Europe as an American, you get used to the slippery attitude people here have towards the U.S. Most often, the first thing you land on is a bullet point-like critique of the usual suspects — fast food, foreign policy, privatized healthcare, college loans — that millions of Americans would unhesitatingly agree with if it weren’t for the facilely dismissive sprit in which such commentaries are frequently offered. The funny thing is, alongside this generalized, almost rote disdain, you are just as likely to come across an openly intense love for American things, often within the same conversation. I’ve lived in Spain for close to three years now and have met many Europeans more obsessed and encyclopedically informed about American music than any native I know; on one occasion, a guy was even able to specify which areas of Brooklyn different indie-rock groups were from. This fandom also applies to American television shows (I’ve run into more than a few cases of Breaking Bad delirium) and sports teams (oddly enough the Bad Boys-era Pistons are fondly recalled by more than a few people, a poignant throwback to home for me, since I grew up basketball-obsessed in Michigan in the 1980s), never mind Europe’s devotion to Facebook, iPhones, and other recent revelations of American capitalism.

Instead of being rankled by this incongruity — if it is in fact that incongruous — I enjoy and relate to it, even if I could do without the dash of European superiority. U.S. culture stirs a mix of feelings both good and bad, at home and abroad. While I could go on unpacking these transatlanticisms, they are really just a roundabout way of introducing Hopper, an exhibition which strutted into the love-hate pas de deux between the Old World and the New this past summer, kicking off at the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid before moving on to Paris’s Grand Palais, where it will be until January.

The work of Edward Hopper represents a helping of Americana that Europeans are eager to embrace, according to Tomàs Llorens, the Honorary Director of the Thyssen and the co-curator of the exhibition. “Hopper is one of the four or five most important painters of the 20th century and he’s extremely popular here,” Llorens said when I spoke to him on the phone before visiting the museum. He explained that Hopper is not seen as just another cultural import from the U.S. “For European spectators this exhibition is a privilege. Hopper embodies our fascination with the American dream and American life.”

Edward Hopper, then, exists in that exempt category of appreciation, which manages to bracket the lesser products of American culture commonly rejected by Europeans (which also happen to be the most ubiquitous and fiercely exported overseas: McDonald’s, Hollywood dreck, plastic pop music, et cetera.) A lemony nuance is that in America, Hopper’s work has provided an aesthetic so attractive and singular that it has formed the basis of an iconography packaged into a mass-marketed consumer experience: think of moodily lit tobacco ads of a glamorously lonesome man or woman smoking, or fast food chains selling happiness framed in a window. And yet so many years and Hopper-esque ad campaigns later, the actual paintings still maintain their purity of intent, their ability to affect as all great art does. As Llorens suggests, Hopper’s work persists in speaking to people today both in spite of and because of their Americanness — its appeal comes from how Hopper summed up a certain idea of America, yet at the same time universalized his home into images practically anyone can relate to.

¤

I visited Hopper on a Spanish scorcher this past July. Showcasing 73 works in all, the exhibit was the largest collection of Edward Hopper’s art ever shown in Europe (it has since set the Thyssen’s all-time record for ticket sales, and was voted best artistic offering of the year by readers of El Pais.) As I entered the show, I read about the time Hopper spent in Europe as a young man — mostly in Paris, with trips to Holland and Spain — only to return to the U.S. in 1910 and never cross the Atlantic again. He kept mainly to his Washington Square studio over the years, a lifestyle suited to his solitary nature. (His wife Josephine famously remarked, “Sometimes talking to Eddie is just like dropping a stone in a well, except that it doesn’t thump when it hits bottom.”) The artist’s enigmatic gaze in Self-Portrait (1925-30) met with visitors’ as they stopped at a timeline of his life at the show’s entrance before continuing on to the work from his brief European period. These pieces were the most un-Hopper-esque, the least iconic, and probably not at all what the public in Madrid would be coming to see.

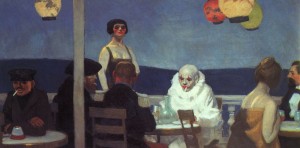

Soir Bleu, Edward Hopper; cc Some rights reserved by dchurbuck

Take, for example, Soir Bleu, from 1914, which the exhibition materials call “the masterpiece that summarizes and concludes Hopper’s years of study and learning.” The painting is of a café scene in Paris. Three tables are pictured with colored paper lanterns hanging above them. A bald off-duty clown in white sits at one, an elegantly dressed couple at another, and a working class man, smoking, at the third. A haughty woman in a green dress stands apart, watching the café’s patrons; she is nearly as pale as the clown, and her rouged cheeks and bright red lipstick indeed suggest a clownishness to her self-regard. Even with so many characters, the work has Hopper’s signature suspended air of aloneness, his full-bodied sense of volume. Objects look solemn and weighty (wispiness is a quality which doesn’t exist in the world of Hopper.) Yet Soir Bleu doesn’t move you, doesn’t thump, or at least it didn’t for me. The painting may have been critical to his future development, but since I was aware of the American scenes awaiting me further on, Hopper’s pieces set in Europe felt thematically unpronounced, with little to differentiate them from the work of any young artist of that time doing his Grand Tour. It’s as if his trademark solitude only reaches its powerful flowering in an American landscape; his American sense of place is key, as is his intuition for discovering his native land and the individuals who live in it.

These gifts were on robust display the rest of the exhibition, threatening to convert my meander among Hopper’s paintings into a bout of nostalgia for a certain idea of home. Hopper’s America — New England-centered, white, created before Vietnam and its attendant cultural upheavals — is of course unrepresentative of large swaths of national experience, including portions of my own, but it seemed to me, strolling through the galleries, that if you’ve ever felt lonely in a city there is no better reflection of this state than Hotel Room (1931). The young woman sitting on the bed might as well be every lonely American in a city somewhere. She looks down at a book, though it’s easy to imagine she’s not actually reading, too distracted by thoughts of her own miniscule place in the world. And then there was Gas (1940), which, much like many of the other suburban scenes, placed me in a landscape I was helplessly familiar with. The painting, of a red-pumped gas station, left me with the momentary illusion of being on a country road in Michigan as a child, on the way up North for a week of vacation with my family. There I was in Europe, riding in a car back in the U.S.

Gas, Edward Hopper; cc Some rights reserved by dchurbuck

Then came big hitter after big hitter, among them Two Puritans (1945), Manhattan Bridge Loop (1928), and Room in New York (1932), each with a bluntness of presentation, and nakedness of subject matter. They appeared to me to offer definitive statements about what it’s like, respectively, to walk by a house and wonder about the lives inside, to be dwarfed by the cityscape you inhabit but always fail to dominate, and to share a space with someone and still feel alone. Hopper, in all his radiant starkness and poetic play between interior and exterior, sent me back to Marilynne Robinson’s Housekeeping when I got home to my apartment, where I found passages which fell silkily into conversation with the exhibition I’d just seen:

It would be terrible to stand outside in the dark and watch a woman in a lighted room studying her face in a window, and to throw a stone at her, shattering the glass, and then to watch the window knit itself up again and the bright bits of lip and throat and hair piece themselves seamlessly again into that unknown, indifferent woman.

Hopper’s work can feel like the moment after that stone is thrown. And then there was a passage which is hard not to read as an explicit reference to Hopper and his most famous painting:

Lucille and I sat across from each other and Sylvie at the end of the table. Opposite her was a window luminous and cool as aquarium glass and warped as water. We looked at the window as we ate, and we listened to the crickets and nighthawks.

¤

It’s been my experience that living abroad has allowed me to discern with a heightened sense of clarity what I like and dislike about the U.S., something I thought about as I browsed Hopper. Beckett elegantly overstates this phenomenon, of seeing your home clearly from abroad, in his novel Molloy: “I fail to see, never having left my region, what right I have to speak of its characteristics.” Of course we all have the right to speak, wherever we are, but distance can equal improved vision. While understanding what I can’t stand about the U.S. has always come easier to me than understanding what I love dearly about it, lately this hasn’t been the case. In fact, I’ve been missing home like never before, and this feeling seemed to reach a sharpened point at Hopper. Perhaps this was because I knew I would be moving back to America in the coming year once my wife’s green card came through, so I could finally allow myself the luxury of homesickness without the fear of it impeding my life in Spain. Perhaps the exhibition let me admit to myself how much I missed English, or reminded me how the things I love most about the U.S. are inseparable from the things I hate, all of it part of the same cultural bedrock. In Hopper’s paintings my jumbled feelings seemed to resolve for a moment, crystallized into a more refined appreciation for a home unattainable if I hadn’t left it. Maybe, like Hopper, I had to go to Europe to really see America. In my case this felt like a personal flaw of sorts, but one I had no choice but to cherish.

Still wandering the show, I settled down on a bench next to an older man who sat facing East Wind Over Weehawken (1934) and asked him if he found the American scenes ajeno — a word meaning unfamiliar or alien. “No, the American scenes aren’t ajeno to me,” he said, noting that he was a movie buff and had seen more than enough American movies to feel a kinship of sorts with the landscape. To underscore his point he gestured to a nearby painting, which I hadn’t noticed: House by the Railroad (1925). “That’s the house from Psycho,” he said. Sure enough, it was; I later read that Hitchcock referred to the gothic house Hopper captured as “California gingerbread,” and although this was news to me, it shouldn’t have been, considering Hopper’s uncle-like influence on film in the U.S. and Europe. German director Wim Wenders went so far as to recreate the Nighthawks diner tableau in his 1997 The End of Violence, and the exhibition acknowledged this debt by having American cinematographer Edward Lachman put together a life-sized, set-like mockup of Hopper’s 1952 work, Morning Sun, which visitors were invited to snap a cell phone shot of through a picture frame. As Slavoj Žižek puts it with forceful simplicity, “Edward Hopper should also be included among the noir auteurs.” Indeed, during the exhibition I kept almost hearing a voiceover from Phillip Marlowe in my head.

“I find the American landscape alien,” said Chaque, a 37-year-old electrician and frequent museumgoer I talked to, even though he, like many Europeans, had visited New York City. He didn’t see the American dream in Hopper’s work and balked at the suggestion that he is widely known outside the museum crowd in Spain. “There are a lot of people who aren’t familiar with him,” he said. (He turned out to be right; a number of Spaniards I know who I expected to have heard of Hopper hadn’t.) A subtext of Chaque’s commentary, at least to an ear like mine, overly sensitized to perceptions of the U.S. in Europe, was that Hopper’s renown will never match that of, say, Nike, or Tom Cruise’s face. Of course I already knew this, long used to the unique mixture of disappointment and shame I experience when someone I talk to in Spain who likes to read, and the reader has heard of, say, Dan Brown but not James Salter. Nevertheless it felt like an especial disgrace there in the gallery, pleased as I was to imagine I was sharing Hopper with all of Europe, his paintings bringing us together in an uncomplicated appreciation of an American creation truly deserving of export, though that surely isn’t the right word. Commerce beats out art almost every time, as we all know, however much they often go hand in hand. After all, there was only one way to leave the Hopper exhibition: the exit through the gift shop.

The image that I left the museum with after passing the stacks of books and the rows of postcards was a kind of meta-Hopper moment, like a present-day recreation of one of his paintings, both an extension of his work, as well as a commentary on it. A teenage couple stood quietly together in front of Office at Night (1940), a scene showing a man and woman at work, both figures looking terribly, almost voluptuously alone, separated by a space of silence. I thought of the sense of loneliness with which life seems to throb during adolescence and I wondered what these two teens were thinking and feeling. The boy wore a shirt that said, Anti-capitalists, Let’s Take Action! I stood behind them and the two appeared as framed by the painting as the two figures on the canvas. I thought of how, as an American framed by Europe, the fact of my origins, no matter how assimilated I had become, how well integrated, still determined introductions or guided conversations. This frame would fall away soon and I felt ready for it.

¤

It’s December now, five months after I saw Hopper, and in two weeks I’ll be moving back to the U.S. I hope I’m not suffering from — or at least only partially suffering from — a sentimental symptom of distance D.H. Lawrence describes related to his native England (found, naturally, via Geoff Dyer): “A hopeless attraction, when one is away.” Regardless of how my return home goes, I feel sure that soon Spanish scenes will strike me with a force they never did before, perhaps with a similar sense of nostalgia and longing that Hopper’s America did while I was in Europe. My wife and I will frame one of Antonio López’s panoramas of Madrid and put it on the wall of our new apartment and I will think of a place that became home: cañas with friends in the evening, tapas with my in-laws, the old buildings and picturesque plazas. I will miss Spain.

¤

LARB Contributor

Aaron Shulman is a freelance journalist who has written for The New Republic, The American Scholar, and The Awl, among other publications. A former Fulbright scholar in Guatemala, he spent a few years in Spain, and now lives in Los Angeles.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Wood Boy Dog Fish: An Interview with Sean Cawelti of Rogue Artists Ensemble

TO CALL WOOD BOY DOG FISH — a production of the Rogue Artists Ensemble that recently had a run at the Bootleg Theater — a play would be a disservice...

Light In Translation: On Spencer Finch

Revisiting the poetry of past installations

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2013%2F07%2F1356887082.jpg)